"Welcome to Mrs. Mannerly's School of Manners!" With this single embracing sentence, we are admitted entrance into a refined world of courtesy and decorum. On surface the second-floor rumpus room at the Steubenville, Ohio, YMCA is hardly an elegant locale. But back in 1967, when ten-year-old Jeffrey Hatcher was a wide-eyed, bow-tied student, Mrs. Mannerly's eight-week etiquette class transformed the Y into a magical place, a genteel bastion that sought to hold back the tide of an increasingly strident world. Mrs. Mannerly, which is enjoying an aptly charming staging at Max & Louie Productions, is Hatcher's delightful yet melancholy valentine to lost innocence.

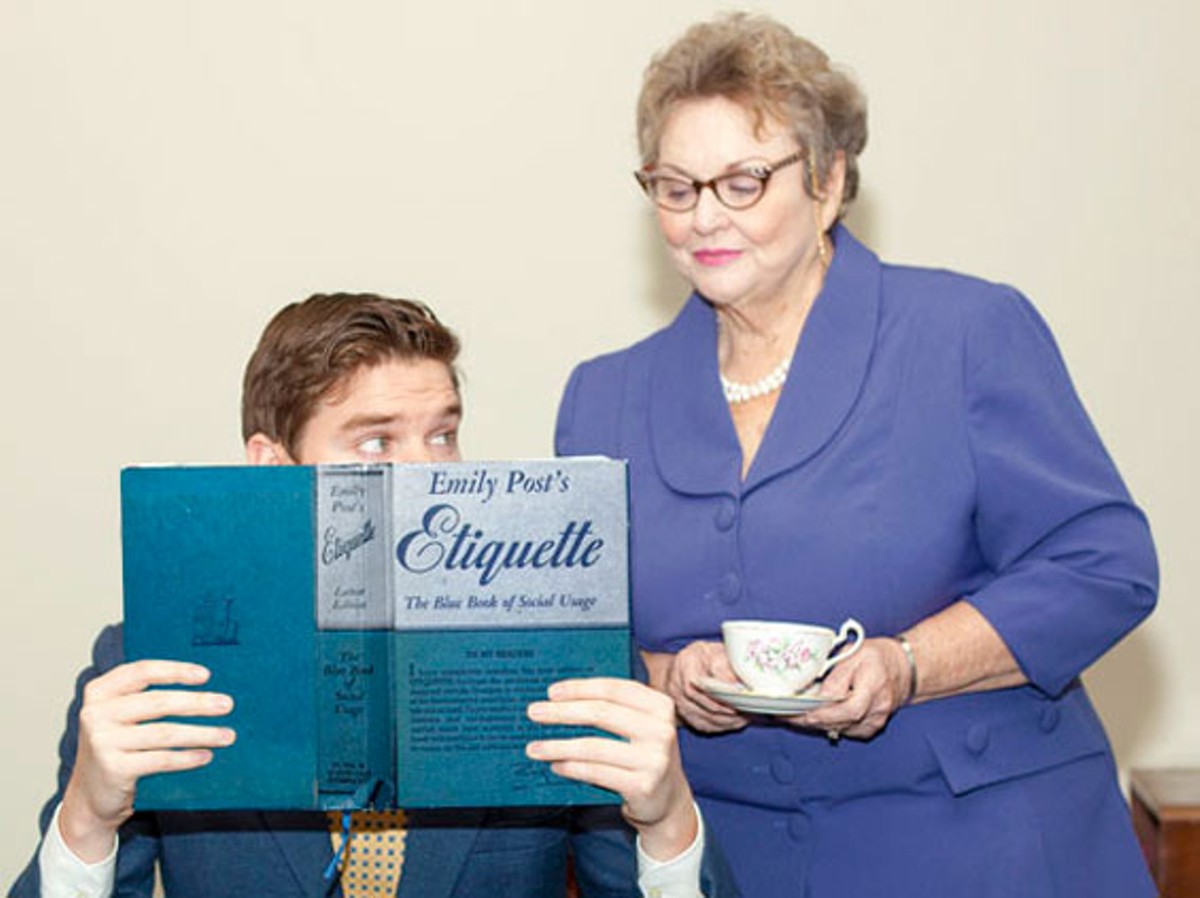

After Hatcher left Steubenville, he grew up to become a prolific playwright (Tuesdays with Morrie, Ella, Compleat Female Stage Beauty). But by the time his scripts began to be produced, large-cast plays were as extinct as etiquette classes. Mrs. Mannerly is in the same "child falls under spell of charismatic grande dame" genre as Auntie Mame. But whereas that 1956 comedy sports a cast of thirty, Mrs. Mannerly must make do with a company of two. Donna Weinsting enacts the title role with a sweet dab of quiet desperation; the ingenuous Charlie Ingram portrays Jeffrey and everyone else.

Director David Hemsley Caldwell aims for chuckles rather than guffaws. (Mrs. Mannerly would not have approved of crass laughter. One of her staples of sage wisdom: "Don't draw attention to yourself.") And there are layers here beyond mere jokes. Mystery, for instance, as when (rather like in Agatha Christie's Ten Little Indians) one by one the students begin to vanish from the class. There's even violence afoot: One student tries to scoop another to death with a melon baller. (You don't see that in Auntie Mame.) We can assume that with the passing years, Hatcher's memories have grown exaggerated. But he keeps the 70-minute evening compact. For delivering such a tidy and deft vignette, surely Mrs. Mannerly would award her prize pupil extra points.

While Mrs. Mannerly recalls an eight-week etiquette class with only two actors, An Iliad at Upstream Theater ratchets the storytelling bar higher still and chronicles ten years of war with but one. Identified as The Poet, Jerry Vogel initially seems to have more in common with the lusty Zorba the Greek than with the elusive Homer, who presumably wrote this ancient Greek poem about the Trojan War. At first our jaunty interlocutor is reluctant to embark upon his marathon (95 minutes) retelling. But once he begins ("imagine a beach"), and we do battle with the heroic likes of Achilles, Hector and Patroclus, the poet becomes a steward to his tale of pride, honor, greed and jealousy.

Director Patrick Siler is insistent that we in the audience follow this story. To that end, even though Vogel strides the stage solo, he is never alone. For starters, his colorful storytelling is augmented by live music from composer Farshid Soltanshahi, whose accompaniment enhances the pace of the more gripping sequences. Vogel is also buoyed by a lighting plot, designed by Joseph W. Clapper, that does not fear to kick into overdrive. Is it flashy? Yes. Does the lighting sometimes call attention to itself? Sure. But why not? There's no need for pretense; we know we're in a theater. So the lighting warps Vogel's face into images as gruesome as the dead he describes. At times the lighting would persuade us that Vogel is not even Greek; he is a Japanese kabuki actor, and the conflict he recounts might have occurred on a beach in Iwo Jima. Indeed, one of the reasons for this 2012 adaptation by Denis O'Hare and Lisa Peterson is to universalize the great-granddaddy of all war sagas.

What word is most often repeated? "Rage!" Dismiss the poet's early reference to "the distant ring of glory." There's little glory here. At the end of a decade of debilitating war, these soldiers are weary. They care not about the captive Helen of Troy. "Just give her back!" they thunder, and in an evening where verbiage showers down upon us like spears, the sinewy strength of the one-syllable word in a declarative sentence is confirmed anew.