Editor's note: The writer obtained unreleased police records for this story. The narrative also is based on interviews, court documents and Internet comments.

Noor Almaleki typed a text message to a friend.

"Dude," she wrote at 1:06 p.m. last October 20, "my dad is here at the welfare office."

Noor, age twenty, hadn't seen her father, Faleh, since she moved out of the family home in Glendale, Arizona, a city about nine miles outside of Phoenix, months earlier.

But his presence both startled and alarmed her. She knew he wouldn't rest until he'd regained complete control of her life.

Noor was the first-born of Faleh and Seham Almaleki's seven children. Her first name means "light of God." The Almalekis had moved to the United States from Iraq when Noor was four.

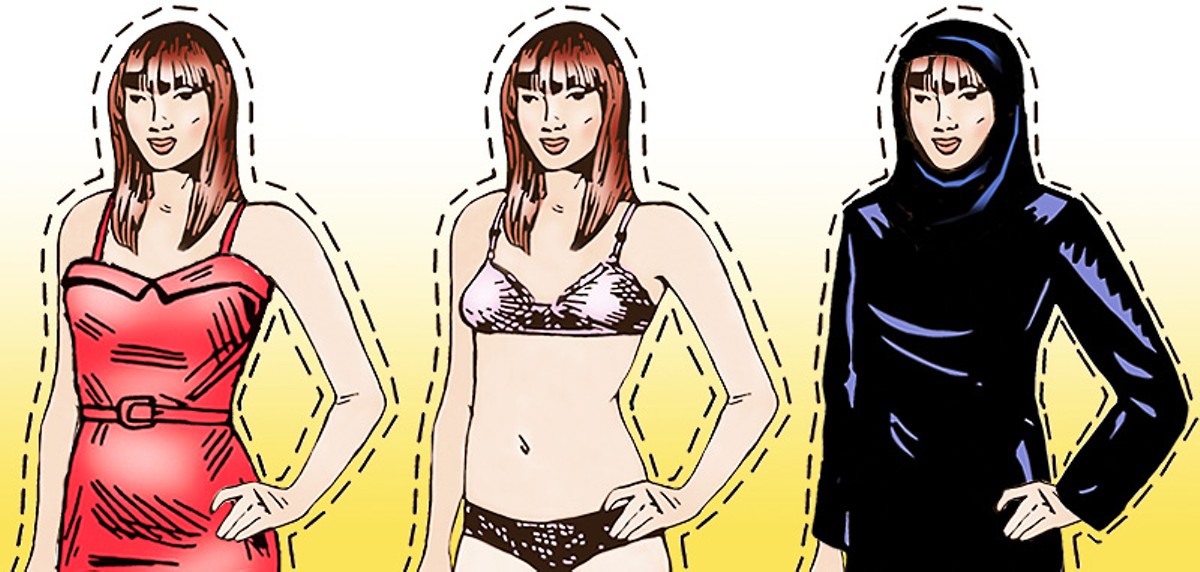

Noor was thoroughly assimilated into American culture but kept in touch with her Iraqi roots (she was fluent in Arabic) and considered herself a Muslim, the same religion as her parents. But she had moved away from her parents in early 2009 (not for the first time) after another blowup over how she was living her life — tight jeans, makeup, boyfriends, modeling photos and an attitude that screamed independence and self-determination.

The clashes escalated in 2008 after Noor, who was eighteen at the time, left her marriage to an older cousin in Iraq — her father had "arranged" it — and returned to the Phoenix area.

Noor sent her text message from inside an Arizona Department of Economic Security office. Seated next to her was Amal Edan Khalaf, her boyfriend's 43-year-old mother.

Amal was there to complete a change-of-address form for welfare benefits. She too is Iraqi by birth, but moved to the States only about a decade ago, and her proficiency in English was such that Noor came along to help translate.

Noor had lived at Amal's residence since leaving her parents' home after the latest fracas.

It was bad enough that she was living with Amal, whom Faleh and his wife, Seham, had known for years and considered unfit as a mother and wife (she was separated from her husband at the time).

Noor's boyfriend and Amal's son, nineteen-year-old Marwan Alebadi, also lived there, and the Almalekis — particularly Noor's father — were enraged and shamed by the situation.

From their perspective, a man's daughters are his property, and they are supposed to live with him until he decides otherwise.

Females who stray from the fold — or are perceived to have strayed — are considered guilty of dishonoring their clans. To an Iraqi there's nothing worse.

The alleged wrongdoing often revolves around sexual "immorality," but not always.

Riffat Hassan, a retired University of Louisville professor and expert on the Koran, says, "Muslim culture has reduced many, if not most, women to the position of puppets on a string, to slavelike creatures whose only purpose in life is to cater to the needs and pleasures of men."

The Almalekis were proud members of that "Muslim culture."

By moving in with Marwan and Amal, Noor Almaleki had made it clear that she would not be her father's puppet, his "slavelike" creature.

She was determined to live how — and with whom — she wished.

Some cultures, including the Almalekis', endorse ancient methods of "cleansing" a family's supposedly tarnished name — with the blood of its daughters, sisters and wives.

In India, Hindu and Sikh brides are sometimes slain because their dowries are considered inadequate, the United Nations Children's Fund reports.

In Islamic Middle Eastern countries, there's a name for the homicides of women by male family members: "honor killings."

These murders of loved ones are as personal as it gets, usually committed with knives, machetes or bare hands.

Victims have been tied up and buried alive. The father and grandfather of a sixteen-year-old Islamic girl in Turkey did just that a few months ago, after someone reported seeing the girl talking with boys.

No one can say exactly how many "honor killings" occur, but anecdotal evidence (from news accounts and government data) suggests that hundreds of Muslim women and girls die this way every year.

According to a 2006 statement by a U.N. news agency, 47 women died in "honor killings" in 2006 in Basra, Iraq, seaport city of about 4 million people, and Faleh Almaleki's hometown.

Such killings by Muslim immigrant men are reported in Western nations as well: Five were accused of murdering female kin in the United States between the start of 2008 and October 20, 2009.

That was the day Faleh Almaleki, an unemployed 48-year-old trucker with no criminal record, took a terrible step toward adding himself to that list of accused "honor" murderers.

Noor sent a second text message after her father stepped into the DES office, this one to her best friend, Ushna.

"Dude, I'm so scared. Shit," she wrote. "At the welfare place, and guess who walks in? My dad!!! I'm so shaky!"

"Holy shit, did he see you?" Ushna quickly responded.

"I don't think so," Noor typed. "His fat ass is right by the door so I can't even leave. I'm laughing like a crazy person. I hate when this happens to me. I knew I shouldn't have [woken] up."

"Oh, dear, that's awkward," Ushna said. "What's up with your parents, anyway?"

"My dad is a manipulative asshole," Noor replied. "I've honestly never met anyone...so evil."

Amal Khalaf watched as Faleh took a number at the counter and then sat near her and Noor.

Faleh was on his own cell phone around the time that his daughter was texting. He spent five minutes speaking with his oldest son, Ali, eighteen months younger than Noor.

Faleh also spoke with a male relative in Detroit, Michigan, and several times with his wife, Seham, who was working as a translator at a U.S. military base in California.

Minutes after he arrived, Faleh left the DES office without comment.

At 1:32 p.m. Noor sent a final text to Ushna in which she seemed more relaxed.

"What time do you get out of work?" Noor asked her friend. "Are you going to have time [to meet]?"

Amal's number finally got called, and she and Noor stepped up to a counter to take care of business. That took several minutes.

Amal had parked her van near the front door, in a crowded lot the DES shares with a popular Mexican restaurant about 100 yards west.

But Amal remained wary of Faleh. She knew how angry he was with her for allowing his daughter to move into her home.

Their families once had been friendly, in Iraq and then in the States. Amal Khalaf had baby-sat the Almalekis' young children when Seham was working.

But any good feelings evaporated after Noor moved in with Marwan and Amal.

Amal wanted to scope out the parking lot for Faleh and his 2000 silver-gray Jeep Cherokee before leaving the DES office with Noor.

Noor didn't seem as worried.

She said her dad might spit on her if he had the chance — nothing more.

The coast looked clear, so they headed for Amal's van. But Amal soon discovered that she had locked her keys inside the vehicle.

She and Noor retreated to the DES office to regroup. Amal called her son and asked him to bring by a spare key from home, about twenty minutes away.

It was a sunny, 85-degree day, and Amal wanted to wait just outside the front door of the DES office.

But Noor was thirsty. She suggested they go to the nearby Mexican restaurant for a cold drink. The pair walked west along the sidewalk next to the office and started across the lot.

Seemingly out of nowhere, Amal saw a vehicle coming right at them. She lifted her hands in defense, as if to stop the inevitable.

In that moment, she could see Faleh Almaleki behind the wheel.

The Jeep smashed into the women.

It dragged Noor across a curbed median and left her splayed on the pavement, unconscious and bleeding.

The impact hurled Amal Khalaf about 27 feet. She suffered a broken pelvis, broken femur and myriad cuts and bruises, but she remained conscious.

Police later estimated that the SUV was moving as fast as 30 miles per hour.

Faleh sped out of the parking lot.

Noor was barely alive, having suffered massive brain and spinal injuries, as well as innumerable broken bones.

Amal quickly provided police with a motive. She said the Almalekis were furious with both her and Noor for the current living arrangement.

Amal explained that Faleh had been hell-bent on showing her and his daughter who was boss, who was in control.

Within minutes of Faleh's fleeing the bloody scene, he spoke by cell phone to his wife, to their son Ali and to at least two other members of his extended family.

Cell-tower records show that he called his cousin, Jamil Almaleki, less than an hour after the assaults, about half a mile from Jamil's Phoenix home.

It's uncertain whether Faleh stopped there on his way out of town, to get the clothes and money he was later captured with.

Another possibility is that Faleh packed the clothes and money, days' worth of insulin to treat his diabetes and his U.S. passport (he had recently become a naturalized citizen) before driving to the DES office — which would indicate a planned attack.

Whether Faleh assaulted the women on the spur of the moment or premeditated his action, he had time to reflect on what he would do after encountering Noor and Amal in the DES office: run over two defenseless women, one of whom was his first-born child.

Three police detectives from the Phoenix suburb of Peoria went to the Almaleki residence at 5 p.m. on October 20, about three hours after the assaults.

Noor's brother, Ali, opened the front door. He was in a tough spot.

Ali once had been close to his sister.

His written praise accompanies a photo of the siblings in Noor's senior high school yearbook:

"I admire that my sister is always there for me. I'm always able to talk to her no matter what. She'll always be there for me to listen to and give me a shoulder to lean on."

But the feud between Noor and their parents had taken its toll, and the siblings hadn't spoken in weeks. (Ali later told friends in an e-mail that he had taken to calling his sister vile names before they stopped speaking.)

Ali told detective Juan Lopez that he hadn't been in touch with his father since midmorning, when they had gone to a Best Buy electronics store together. He insisted that he didn't want to get involved in whatever was going on.

But it was too late for that.

Ali already was involved.

He told detective Chris Boughey that things at the house had been increasingly strained since Noor had returned from Iraq after leaving her arranged marriage.

To Ali's way of thinking, doing that had dishonored the Almaleki family.

Ali said Noor had been "most disrespectful" to their parents (to him, too) since her return and had continued to reject "traditional" Iraqi values.

The young man mentioned his own problems with his father, whom he described as a chronic gambler who liked to frequent Phoenix-area casinos.

Ali's mother, Seham, had been calling him over the past few hours, he said, saying that something had happened to Noor.

But Ali swore to detectives that he didn't know what had happened to his sister.

Detective Boughey returned to his car after the interview but didn't immediately leave. Ali came out a few minutes later and told Boughey he wanted to add some details to his account. This time he said he had spoken with his father at 2:30 p.m. (about half an hour after the assaults), but he couldn't recall the substance of the conversation.

Ali let on that he had seen television coverage and wanted to know where Noor was hospitalized. The detective said he couldn't tell him that right away.

Faleh Almaleki crossed the Mexican border into Nogales, Sonora, about the same time that Ali was being questioned in Glendale. Faleh soon parked his Jeep in a mall parking lot and checked into a hotel.

At 5:30 p.m. he made a call to his Phoenix cousin, Jamil.

The next day, October 21, Peoria police issued a warrant for Faleh Almaleki's arrest, alleging (at that point) two counts of aggravated assault.

That day a detective contacted Noor's mother by phone. Seham Almaleki said she was driving back from her job in California. She claimed all she knew was that there was a family problem of an unspecified nature.

Detective Bill Laing told Seham that her husband had intentionally slammed into Noor and Amal with his Jeep and fled.

"This woman is a liar. This woman is dirty. Her family is dirty," Seham told Laing, referring to Amal Khalaf. She said repeatedly that she hadn't communicated with her husband about the incident.

Laing told Seham that Noor's condition was grave. She replied that she wanted to see her daughter as soon as possible.

But the detective said he was concerned that Seham and others might pose further danger to Noor.

"I'm a danger?" Seham shouted.

Ironically, given the circumstances, she continued, "I'm a Muslim. We can't kill our daughter."

On October 22, two days after the assaults, a Glendale pharmacist told police that someone had phoned in a prescription for Faleh Almaleki.

That evening members of Noor's family (including her mother) and many of her friends held a candlelight vigil at the site of the assault. The media were there to capture the moment. The case was generating more buzz with each passing day.

Faleh Almaleki remained a fugitive as his daughter, comatose and unresponsive, clung to life.

Noor's photos, many of them lifted from her Facebook and MySpace pages, were displayed on sites across the Internet. They showed a beautiful young woman with long black hair and a wistful expression.

Noor rarely smiled in the photos, possibly because of embarrassment over braces she had worn for a while. But her friends say she was naturally upbeat, blessed with a sassy sense of humor that she employed even when times were tough.

"Noor, Noor, Noor. How can I describe Noor?" says one female pal who spent hours on end chatting with her at a coffee shop near Glendale Community College, where Noor was a part-time student.

"She was a trusting, loyal person who would calm everyone around her. She was an angel. Like a lot of us [Muslim women], she could be private, but she told me that her dad didn't understand her.

"We have to respect our parents, but she said he wanted her to be this perfect Arab woman, not questioning or demanding anything — 'Whatever you say, Father'— and that just wasn't her."

On October 24, Ali Almaleki spoke with a television reporter about his sister.

He said she had been "going out of her way being disrespectful [to their parents]."

Ali continued, "The boy [Marwan Alebadi] that is supposedly her boyfriend now — I don't like him."

He contrasted Iraq and the United States, saying, "Different cultures, different values. One thing to one culture does not make sense to another culture."

But he noted that seeing Noor at the hospital "just broke my heart. Nobody should have to go through that."

Ali said his father had called home the previous day to ask about Noor's condition, but "my mom yelled at him and hung up."

That day Peoria detectives learned that on October 22 a young man, possibly of Middle Eastern descent, and a woman wearing a veil had picked up a prescription for diabetes in Faleh's name.

Detectives returned to the Almaleki home on October 26 for a follow-up interview with Ali and his mother, Seham. By now the detectives had examined phone records, which showed that Faleh had been in touch with his immediate family and others around the time of the assaults.

Seham admitted that she had lied in her earlier interview with police, but she continued to deny knowing her husband's whereabouts.

Mother and son also admitted they had picked up the medicine at the pharmacy. But Seham insisted she had thrown the pill bottles out of her car window, though she couldn't come up with a reason for having done so. Seham again blamed onetime friend Amal Khalaf for what had happened in the DES office parking lot.

Amal got what was coming to her, Seham spewed, because she is the matriarch of a family supposedly flush with drug abusers and thieves. By contrast, Seham told the detectives, "We have a good family."

Ali told her, "No, Mom. We don't."

Later that evening Ali Almaleki met with detective Boughey alone at a restaurant.

Out of his mother's presence, he provided new details of his father's call to him before the assaults. Faleh had just seen Noor and Amal at the DES office. He said his father sounded angry, so he told Faleh to go home. But Ali said Faleh phoned later to say he had run down Noor and Amal with his car.

During the conversation Faleh told Ali to "man up," because he wouldn't be around anymore.

On October 27, British Customs officials informed U.S. immigration authorities that Faleh Almaleki was in custody in London. He had arrived on a plane from Mexico City using his own name and his U.S. passport. A computer check showed that Faleh was a wanted man in Arizona.

British Customs put Faleh on a Delta flight to Atlanta, Georgia, where the feds have a port of entry for incoming fugitives.

On October 28, Mexican authorities in Nogales contacted Peoria police. They had found Faleh's Jeep — the missing weapon — in a mall parking lot. Crime-scene investigators later found hair, fiber and human tissue on the vehicle.

On October 29, Peoria detectives Chris Boughey and Jeff Balson sat across from their suspect in Atlanta.

Faleh Almaleki waived his Miranda rights against self-incrimination, which meant the detectives could question him.

At first Faleh told them he had run over the two women in a freakish accident after coincidentally finding them at the DES office.

"If I want to try to kill my daughter, why would I kill my daughter with vehicle?" he asked, trying to sound reasonable. "I have no problem with my daughter; this is not the first time she left the house.... If I want to kill her, I go buy a gun. I know where they live. I just lost control [of the car]."

Detective Boughey asked him whether he had been trying to scare the women.

"Might be something like this," Faleh claimed, "but I don't try to kill them."

The detectives picked away at the murky account.

"I've been angry," Faleh replied, "and I lost control. I lost the brain."

But he continued to insist that he had not premeditated his actions.

Like his wife, Faleh faulted Amal Khalaf for having "stolen" their twenty-year-old daughter from them.

He insisted that he loved Noor, noting that his cell phone contained several photos of her. But as if it were a self-evident truth, Faleh said his daughter should not have become so "Americanized" — that it was wrong.

Faleh said he had stayed at the Nogales hotel for two nights, during which time a "stranger" gave him about $1,900 in cash for his Jeep and agreed to make sure some "paperwork" got to Ali.

Though unconfirmed, a far more likely scenario is that Faleh's cousin, Jamil Almaleki, or someone else close to the Almalekis delivered the money, diabetes medicine and clothes that Faleh had with him when British authorities collared him.

Jamil Almaleki could not be contacted for this story, and police reports suggest that he may have returned to Iraq.

Faleh said that while he was in Mexico he hopped a bus from Nogales to Hermosillo, and then flew to Mexico City. Within a day he boarded a Mexicana Airlines flight to London, where his desperate flight from the DES parking lot abruptly ended.

Detective Boughey asked Faleh whether his family was on his side. Perhaps, the detective said, his attack had restored some of the "honor" supposedly lost by Noor's lifestyle choices.

Faleh didn't reply directly, saying he would certainly help a friend or family member in a similar predicament.

"It's our culture," he explained.

Faleh asked the detective what he would do if he had such a disobedient daughter.

Boughey responded that he would not crush his daughter with a car. He soon asked Faleh again whether he had meant to hurt the women.

Yes, Faleh Almaleki finally confessed, he had.

"If your house has got a fire [in] just part of the house," he said, "do we let the house burn or [do] we try to stop the fire?"

Faleh then admitted that his daughter Noor was the "small fire" he had to extinguish.

He was booked into Georgia's Clayton County Jail and waived extradition. On October 31, the Peoria detectives escorted him back to Arizona on a commercial airline.

At Faleh's initial appearance in Phoenix later that day, a judge set his bail at $5 million.

Doctors at John C. Lincoln North Mountain Hospital pronounced Noor Almaleki clinically brain dead at 7 a.m. on November 2, 2009.

Her family decided to take her off of life support. Several of Noor's relatives — including her mother and brother — were by her bedside when her heart stopped beating at 11:54 a.m.

Police noted at Noor's autopsy that her eyes, so hauntingly beautiful in photographs, were swollen shut.

Days later in Arizona, a Maricopa County grand jury indicted Faleh on charges of first-degree murder, attempted first-degree murder, aggravated assault and leaving the scene of an accident.

Noor's violent death struck a nerve worldwide, especially after a county prosecutor officially attached the phrase "honor killing" to it.

To some she would become a symbol of the ills said to infect Muslim culture, ills that would allow a father to slaughter a daughter with the blessing of at least some family members.

The sad case captured the attention of Rana Husseini, an expert on "honor killings." A reporter for the English-language Jordan Times and author of Murder in the Name of Honor, Husseini has written about dozens of such crimes in her homeland.

"I wish that poor girl had been able to stay safe, maybe in a shelter or something," Husseini says. "It's such a waste of a life."

In Jordan and elsewhere in the Middle East, men who commit such killings often receive lax punishment — sometimes only getting sentenced to months, if that, behind bars.

Faleh Almaleki's fatal attack on his daughter fit the pattern of a typical "honor" crime in the Middle East. The differences are that Faleh used a vehicle instead of a knife or machete and that, if convicted, he will probably spend the rest of his life in prison. ( The county attorney's office is not seeking the death penalty.)

Someone created a Facebook page within a few days of Noor's death: R.I.P Noor Faleh Almaleki. Its home page asked that Noor and "all other victims of senseless honor killings rest in peace. And may God be the guardian of others in danger of sharing that fate. And may we all do something to end honor killings once and for all."

On the "wall" that is part of the page, more than 3,000 people have written about Noor, her tragic death and Muslim culture.

A typical entry, written by an eighteen-year-old girl from Maine, says, "I can tell she was a good girl, and when she finally realized she couldn't live her life under another person's decision, she left! I respect her so much for that.

"She is going to live her life in Heaven like she didn't get to live it here on Earth."

Another of those commenting was her brother Ali, who wrote, "What grabs the most attention from this situation is the fact that this is a Middle Eastern family.

"The media has drawn this image that Noor, RIP, was a saint and my dad was the Devil."

Ali said he wasn't "advocating" what his father did, but he insisted that the slaying was unplanned.

"You guys [in the media] be careful what you say," he wrote. "That's my father you're talking about. And my father is a loving man. He loved Noor. That may raise eyebrows, and you guys [may ask], 'Why would he do this if he loved her?'"

Ali's conclusion: "He lost his mind."

Referring to Noor, he wrote, "Nobody deserves this, and this never should have happened. And nobody will ever understand the kind of pain my family is enduring."

Noor Almaleki's life never was the same after she rebelled against her parents and their culture and left her arranged marriage.

She tried on and off over the final eighteen months of her life to live with her family, but it didn't work. Faleh and Seham considered her tainted, someone who had humiliated them by leaving the Iraqi husband her father had chosen for her.

Faleh had gotten wildly angry when, after Noor's return from Iraq, he found a seemingly innocent snapshot of her and a few male friends. In his mind, Noor shouldn't have been chummy with men other than her husband, to whom she remained legally married.

But Noor stood up for herself. She posted a free page on exploretalent.com, a website that showcases aspiring models, actors, musicians and dancers.

The photographs on Noor's page were not racy, just photos of a young woman with a uniquely beautiful face. Noor never paid the $30 monthly fee to find out whether anyone was interested in her "look" for possible modeling assignments.

Noor found work as a server at an Applebee's restaurant, where she made new friends. One of her coworkers, Nicole Ferugia, recalls that Noor quit after her father learned that she was employed at an establishment that serves liquor.

In summer 2008, Noor moved in with a girlfriend's family for a time. That July Faleh asked Glendale police to charge his daughter with felony auto theft after she took his car early one morning (not the Jeep) and got into a minor accident.

Faleh tried to make a deal with her: If she returned home and straightened herself out, he would ask authorities to drop the case against her.

But Noor wouldn't agree to that and wound up facing a serious charge that remained unresolved at the time of her death.

Things continued to deteriorate inside the Almaleki family.

In March 2009, Seham Almaleki won an order of protection against Noor in Glendale City Court. In her petition Seham claimed Noor had come home and hit her on one occasion and had cursed her at the family home on another.

Noor did not contest the order, which barred her from the Almaleki residence and from contacting her siblings at their schools.

By this time, she had moved in with her new boyfriend, Marwan, and his mother. To the Almalekis, that was akin to a declaration of war by Noor, Amal Khalaf and her son.

On July 20, Faleh and Seham broke into Amal's home late at night in an attempt to corral their daughter.

Glendale police reports say Noor and Marwan weren't home at the time. But Seham banged on Amal's locked bedroom door and challenged her to come out and fight. Amal apparently hid until police arrived in response to a 911 call made by one of Amal's young daughters.

Amal declined to pursue criminal charges against the Almalekis.

Some of Faleh and Seham's concerns about their daughter's living arrangement may have been justified.

Last August 6, Glendale police arrested Marwan Alebadi on charges of assaulting Noor, allegedly as she tried to break up his fight with an unnamed third party at Amal's home.

Marwan was accused of breaking and lacerating Noor's nose during the clash, which he denied to police. The domestic-violence charge was pending when Noor died.

At home recovering from her injuries, Amal Khalaf told Peoria police in December that she had taken Noor in because the young woman had nowhere else to go after leaving her parents' house. Giving Noor shelter, not facilitating Noor's romantic relationship with her son, had been her sole concern, Amal stressed.

She said she knew how much Noor missed her younger siblings and that Noor would talk with her sixteen-year-old sister, Fatima, without her parents' knowledge.

Just days before the assaults, Amal said, she had persuaded Noor to reach out to her parents, in an effort to at least get a dialogue going.

Noor spoke with her mother by phone, but Amal said it didn't go well. She reported that Noor told her Seham had declared, "Amal is your mom; I'm not your mom."

In the weeks after his arrest and subsequent incarceration at the Maricopa County Jail, Faleh Almaleki spoke often by phone with family members. Authorities secretly taped every word.

"How is she now?" Faleh asked cousin Jamil during one conversation, which police later had translated into English. (Faleh and his family spoke in Arabic during their jail conversations.)

"Who's she?" Jamil asked.

"Noor," Faleh said.

"Noor died, brother," Jamil said.

"What?" Faleh asked.

"Yes, she's gone, Faleh. Now, look after yourself."

"Brother," Faleh replied, "talk to the lawyers and tell them it was not intended to be a murder."

Faleh told Jamil to ask the Iraqi consulate to intervene with the American government.

"Connect it to honor and dishonor and, I don't know, whatever," he said. "And an Iraqi is worth nothing without honor."

Jamil agreed, saying, "This is the base of the story. Newspapers wrote about this issue. It's happening now, and the Internet and whole world is writing about this subject."

Faleh continued to go over the honor-killing theme in phone calls with his wife.

"Listen," he told Seham, "have [friends] sit across from the [U.S.] consulate [in Iraq] and hold signs saying, 'The Iraqi honor is precious.' Signs saying that I'm not a criminal, [that] I didn't break into someone's house, [that] I didn't steal. You know what I mean? And for an Iraqi, honor is the most valuable thing."

Faleh went on with his riff: "No one hates his daughter, but honor is precious, and nothing is better than honor, and we are a tribal society that can't change. I didn't kill someone off the street. I tried to give her a chance, but no result."

Seham chided her husband at one point for having "rushed into it," presumably referring to his violent acts.

"Seham, don't blame me," Faleh protested. "Can you watch Amal's demeanor and do nothing? You can't. Amal brought it upon her."

"Amal brought it upon her," Seham repeated.

"Verily to Allah we belong, and verily to Him we shall return," Faleh told her.

"Trust in God, and pray to God," he said, "and don't rush and retain a mediocre lawyer."

The subject of legal representation came up in another recorded conversation.

Seham mentioned a lawyer who had "pulled a miracle" in an unspecified case.

"Is he Arab?" Faleh asked.

"No, not Arab," she replied. "He is a Jew."

Faleh paused.

"A Jew?" he said. "Check with Arabs as well. [But] if there is a loophole in this subject — you know, clans, tribalism, something like that — the Jews know of it. See if there is a loophole or something.

"We can say that you have...a psychological problem," Seham suggested. "You have to tell them, 'I am suffering because of the war.'"

Faleh agreed that this would be a good idea.

"Tell them I am tired and feel nervous. I am always suffering from this condition. Tell them I got sick in Iraq. OK?"

Another call between the couple revealed more.

"Noor is gone, Faleh," Seham said, crying as she spoke. "I lost my daughter. My daughter is gone."

"I told you," Faleh replied. "Your daughter was gone anyway."

"No, Faleh," his wife continued. "She's gone! My daughter is gone!"

"Noor is gone, and what about me?" Faleh responded.

"You are gone," his wife concluded.

Faleh has pleaded innocent of the charges against him. A trial date hasn't been set. He will remain locked up in the Maricopa County Jail until his case concludes.

The Almaleki family declined to speak with Phoenix New Times for this article. The family's comments all came from investigation records and posts on websites.

Neither would most of Noor's friends speak on the record, saying they feared her family might retaliate. Noor's boyfriend, Marwan, could not be reached for comment.

The blogosphere continues to resonate with opinions about "honor killings" and about what Faleh's legal strategy should be.

"There's no doubt about it," writes Pamela Geller of the anti-Muslim website atlasshrugs.com. "He ought to be executed."

Though that is the overwhelming sentiment, others have expressed a different point of view.

"Rest in peace, Noor," someone recently wrote on the young woman's memorial Facebook page.

"May Allah forgive her and forgive us for all our sins. And may Allah help her Dad!!!!"