The Cosby Show

Few entertainers, especially comedians, have campaigned so hard to position themselves as role models. Through his signature series, Cosby remade himself into a paragon of responsible fatherhood, marital bliss, and domestic tranquility. Saccharine and square even by the uptight standards of the Reagan era, the show proved through its massive popularity that Cosby's vision of a gentle but firm patriarchal order could cross color lines.

The Cosby Show likely won't survive -- not just because the sitcom's wholesomeness emphasizes the duplicity of Cosby's 2014 persona, but because it's no longer necessary. Even before it went off the air in 1992, it ushered in a burst of black sitcoms during the Clinton years -- Family Matters, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Martin, Moesha, and, of course, Cosby spin-off A Different World -- that exponentially increased the variety of black representation on the small screen. The Huxtables are no longer the only black family on the primetime block.

His Stand-Up

Judging from those recent standing ovations, some audience members may still love Cosby's monologues, but the material that made him a comic legend hasn't aged well. The Village Voice recently rediscovered a bit, for example, in which Cosby jokes about drugging a woman's drink. Divorced from the context of the rape allegations, it feels merely like a hoary sitcom premise. But the intimate nature of stand-up comedy, in particular its crafting of a personality (often based on the comedian) with a history and particularities and likes and dislikes, makes it a medium uniquely vulnerable to scandal and the reinterpretation of statements.

His Politics

After The Cosby Show went off the air, the comedian began using his character, Cliff Huxtable, as a cudgel against aspects of the African American community he considered obstacles to mainstream success. Poverty, mass incarceration, the war on drugs, substandard schools -- Cosby has railed against none of these institutional problems. Instead, he has focused on the need for traditional families and conventional...names ("With names like Shaniqua, Shaligua, Mohammed, and all that crap...all of them are in jail").

The culmination of these socially conservative harangues was the infamous "pound cake speech" in 2004: "These are people going around stealing Coca-Cola. People getting shot in the back of the head over a piece of pound cake. Then we all run out and are outraged: 'The cops shouldn't have shot him.' What the hell was he doing with the pound cake in his hand? I wanted a piece of pound cake just as bad as anybody else. And I looked at it and I had no money. And something called parenting said, 'If you get caught with it, you're going to embarrass your mother.' " In the era of Ferguson, Cosby's characteristic dismissal of law-enforcement racism and civil rights activism reads as particularly tone-deaf. But the allegations of serial rape will likely force Cosby to retreat from public life. You need to possess the moral high ground to tell other people how to live their lives.

Is Any Part of Bill Cosby's Legacy Worth Salvaging?

How you separate the art from the artist

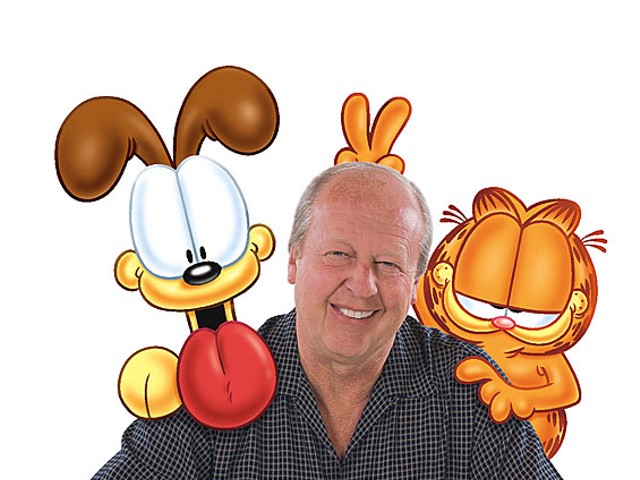

A promotional image for The Cosby Show.

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "41932919",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]

Bill Cosby's present is secure. Despite the 17 women (so far) who have publicly come forward with notably similar allegations of drug-enabled sexual assault, the comedian received standing ovations for his stand-up performances in the Bahamas and in Florida recently. His comeback tour will likely continue over the next few months. A handful of venues have canceled his engagements, but more than two dozen shows remain on the schedule.

Cosby's legacy, however, may be marred forever. Unsurprisingly, it's the cultural critics who grew up worshipping his TV family -- those who feel the betrayal of The Cosby Show's wholesomeness most acutely -- who have led the charge in renouncing everything the comedian has ever done. Roxane Gay powerfully (if not entirely convincingly) argued that, in the case of Cosby, the choice is "art or humanity": "There is only one side that matters...We have to stop supporting any of his endeavors. His art does not absolve him. Art is nothing compared to humanity, nothing at all." Mike Ryan was no less absolute: "All the good he did -- and his contributions to popular culture really did do a lot of good -- is now ruined."

Gay's and Ryan's desire to do right by Cosby's alleged victims and refusal to financially support the comedian (and thus his legal defense team) are certainly understandable. And it's an encouraging sign of feminist progress, albeit a long overdue one, that Netflix and NBC have canceled their upcoming projects with the comedian and that TV Land has pulled his landmark series off the air. The women who have accused Cosby of sexual assault have been met with a minimum of suspicion about their motives, and rape has been deemed a grave enough crime to kill a career (unlike domestic violence, apparently).

And yet there should be a reluctance to judge an artwork solely by its creator. Chucking all art made by moral failures would leave us with a rather meager culture. More importantly, images and ideas accrue meaning and importance beyond their originators through viewers and readers and thinkers who pick and choose what aspects of a film or TV show or novel matter to them (look at slash fan fiction). Every artwork or oeuvre by a Bill Cosby or a Woody Allen or a Roman Polanski thus deserves a debate about the extent to which its appreciation can and should be divorced from the admiration and patronage of its author. (Can you ever watch the borderline-pedophilic Manhattan the same way again? What about the entirely asexual Zelig?)

In the case of Cosby's art, beauty matters a lot less than ideals -- of familial harmony; of a snappy, sexy marriage among equals; of the peaceful coexistence between black pride and a raceless universe. As reprehensible as the crimes that the comedian is accused of are, I'd like to believe that most people are more than the sum of their worst actions, as naive as that may sound. That holds true even in the face of blatant hypocrisy. Just because Jean-Jacques Rousseau abandoned his biological children doesn't mean his idealizations about childhood weren't useful and lovely; just because Thomas Jefferson was a slave-owner doesn't mean that we as a nation shouldn't strive for democracy and freedom.

Sooner or later, we're going to have to assess, individually and as a culture, which parts of Cosby's legacy are worth keeping (if any), and which are permanently corrupted. Here's a start to the debate: