Finally alone after eleven hours of feverish demands, threats and hostage exchanges, the hijacker pulled off his shaggy brown wig and began to disrobe. He shrugged out of a burgundy sport coat, white dress shirt and yellow trousers — it was, after all, 1972 — revealing a second outfit: a set of dark-colored slacks and a collared blue t-shirt. Upon surveying the rows of empty seats running the length of the Boeing 727, he checked his wristwatch. Only a few hours remained until sunrise.

It was after 3 a.m. on June 24, and the purloined aircraft was hurtling through a cloudy night sky, heading for the Canadian border.

The hijacker, Martin McNally, was 28 years old, but with his boyish face and near-smirk, could pass for a teenager. He scooped up the discarded clothing and walked to the very rear of the plane, arriving at the open hatch and extended stairwell. He stared into the murky darkness below.

There was still time to call it off, McNally thought. He could turn around, walk back to the cockpit and hand his rifle to the pilot. He could return the bag stuffed with $500,000 cash and then, somehow, talk his way out of the mess he'd left back in St. Louis. He could tell the FBI agents that there was never any bomb on the plane, that it was all joke.

McNally tossed the wig through the hatch, followed by the clothing, several smoke bombs and the rifle with its two loaded cartridges. The items whipped into the air and disappeared. This was no time for second thoughts.

Aside from a single hostage, McNally was now the only non-crew member left on the flight. Hours before, on the tarmac at Lambert International Airport, he'd negotiated to release more than 90 passengers in exchange for a fresh crew to fly him to Toronto — a city McNally had no intention of visiting. Soon after takeoff, he'd ordered the sole remaining American Airlines stewardess (through whom he had relayed all of his demands) to join the hostage and flight crew in the cockpit.

Now, McNally's only companion was the thrilling weight of a cash-heavy mailbag tied to his left belt loop.

After strapping on a pair of flight goggles, McNally donned a reserve parachute, tightening the straps around his legs and chest, just as he'd been instructed by an FBI agent during an on-the-spot lesson earlier that evening. McNally had never touched a parachute before. This would be his first jump.

Slipping a handgun into his pocket, he descended the stairs haltingly, on his butt, scooting down step-by-step into the roar of the wind. He turned onto his stomach, catching one last look at the rear hatch leading into the passenger cabin; he imagined how easy it would be for someone on the plane to walk back here and shoot him in the head.

McNally's hands were the only things keeping him connected to the plane. His body, suspended from the stairwell at 300 miles per hour, felt like a daisy caught in a hurricane.

In the cockpit, the remaining crew felt their ears pop as the cabin pressure fluctuated.

One thousand feet above the Boeing 727, from the vantage point of a military surveillance plane, an FBI agent observed a small, dark object falling rapidly from the rear hatch.

McNally dropped like a bullet, feet-first, and the first thing he perceived was the wind punching his flight goggles into his eye sockets. In seconds, the goggles were violently ripped from his head. McNally threw out his arms, bringing his body parallel to the ground as he began counting down from twenty in his mind. Basing his calculations on the formula for terminal velocity — which he'd learned in a library physics textbook — McNally figured that this would be enough time to slow his fall to a safe speed. If he pulled the chute too early, he knew, the air would shred the canopy like tissue paper.

The time came to test his math. McNally fumbled for the ripcord with his right hand, but he made the mistake of leaving his left arm outstretched. Instead of producing the serene, deliberate movements of an experienced skydiver, the wind took hold of his arm and slammed the hijacker into a furious spin.

In the midst of the chaos, the parachute exploded out of the chest harness and ejected its spring-loaded contents directly into McNally's face. Blinded and hurting, he managed to grab hold of the shroud lines above him. He tugged hard, and was rewarded with resistance as the canopy filled with air.

McNally was going to live after all. His hand strayed down to his left thigh, hoping to be reassured by its half-million dollars.

He could only look down in horror. The mailbag was twenty feet below him, and getting smaller and smaller by the second. As if in a dream, McNally watched the fortune tumble in slow-motion, end-over-end, until it slipped below the clouds and vanished.

The hijacker considered his options.

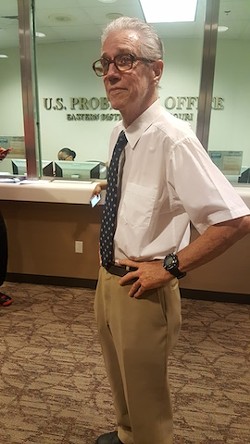

Forty-four years later, on a sweltering afternoon in August 2016, Martin McNally enters the Thomas Eagleton U.S. Courthouse in downtown St. Louis. He rides an elevator to the second floor and checks in at the front desk of the federal probation office.

Clean-shaven, his white hair combed and slicked back from his forehead, the 72-year-old ex-con is anticipating good things from a scheduled meeting with a federal parole supervisor. Five years out of prison, McNally is now permitted to apply for release from his permanent parole, a status that saddles him with travel restrictions and random checkups. The meeting could set the wheels of true freedom in motion.

By the time McNally had been released from a California prison in 2010, he had already spent more than half his life behind bars. He then settled into an apartment in south St. Louis, where he subsisted on disability benefits linked to an old Navy injury.

McNally's first decade as inmate had been marked by violence and multiple failed escapes. He was involved in numerous scraps with prisoners, and, although never convicted, he was twice brought up on charges for assaulting guards in the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. In one instance, he was accused of wielding two sharpened pencils as shanks.

"My first ten years, those were turbulent, no question," McNally says, making conversation in the parole office waiting room. "The guards at the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth were brutal. They beat up and assaulted prisoners; they killed prisoners. So yes, there were assaults on guards, there were indictments."

By the early 1980s, the inmate had calmed down a good deal. McNally dedicated much of the next three decades to appealing his conviction for air piracy. He became a proficient jailhouse lawyer, ran for president and accrued more than $10,000 by illicitly trading Wall Street stocks.

At the courthouse, McNally waits an hour before he and his local parole officer are beckoned into the conference room to meet the supervisor.

The meeting lasts under 30 minutes, and it doesn't look good. During the meeting, the local officer testifies that it would be best to keep the septuagenarian hijacker on parole indefinitely.

On the drive back to his apartment, McNally unleashes a stream of curses, mostly directed at the parole officer.

"I would recommend retaining him on parole," McNally quotes, sneering his impression of the testimony, "because of the nature of this crime."

Fuming, he says, "Yeah, no question, I'll be on parole until I'm dead."

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the"Golden Age" of airline hijacking was an era when any passenger could walk through an airport terminal unmolested, breeze onto the tarmac and board a plane — all that with their shoes on, no less. In some cases, you could even pay for your ticket on board.

This casual freedom — a relic of a more civilized time — persisted in the face of an unprecedented wave of hijackings. Early interventions proved laughably inadequate, flabbergasting airline companies. Ticket agents were instructed to subjectively screen passengers based on a cooked-up checklist of psychological and physical traits believed to be particular to hijackers, and although sky marshals were deployed in 1970, their limited ranks couldn't hope to make a dent in the vast number of flights taking off each day in American airports.

The virtually non-existent security led to a frenzy of hijackings. According to Brendan Koerner's 2013 book chronicling the period, The Skies Belong to Us, more than 130 hijackings were committed in American skies between 1968 and 1972.

Many of the culprits were straight nutjobs, driven by religious or political yearnings that required (for some reason or another) immediate passage to Cuba. But even as the capers escalated in audacity and potential violence, airlines companies balked at beefing up their own security. Instead, they sought to avoid the possibility of violence at all cost. Crews were instructed to comply with hijackers' demands rather than risk an altercation. Pilots on domestic flights were provided with charts outlining passage to Havana, just in case.

But there was a second, altogether different species of hijacker: not a nutjob, but rather a certain kind of foolhardy opportunist. In other words, a common crook.

Driving through Detroit in January 1972, Martin McNally listened with growing interest to a radio news report of a two-month-old hijacking in the Pacific Northwest. Shortly before Thanksgiving, an unidentified man had commandeered a Boeing 727 after taking off from Portland International Airport.

According to the report, the hijacker had ordered the plane to land and subsequently demanded a parachute and $200,000. Upon receipt, the hostages were released, but the hijacker kept the crew and ordered the plane to take off once again. Forty-five minutes into flight, the man jumped from the lowered stairwell at the rear of plane. Both hijacker and cash had seemingly disappeared without a trace.

In the coming months, McNally would spend hours poring through library books on parachutes and skydiving. An idea took root in his mind. The hijacker on the radio — soon mythologized as "D.B. Cooper" — had demonstrated an effective strategy for air piracy, and it seemed a much easier task than knocking over an armored truck or a bank.

McNally was a product of a large family, and had lived most of his life in his hometown of Wyandotte, a suburb in the southern shadow of Detroit. McNally's father, a shoe store owner and respected figure about town, had put eight children through Catholic school. But young Marty McNally spurned his studies. Instead of completing eleventh grade, he enlisted in the Navy, where he labored as an airplane electrician. It was no harbinger of destiny: His flight time was restricted to servicing the cramped patrol craft sweeping for Soviet submarines off the coast of Alaska.

Given a general discharge from the Navy in 1964, McNally had no interest in joining his father at the family shoe store. He wound up scrambling through a series of odd jobs and minor scams, including a plan to embezzle gas sales from a service station and a short-lived counterfeiting operation, which ended when he was busted feeding fake quarters to a laundromat change-machine. By 1972, he was exhausted with the paltry returns on minor scams.

One big score, that's what he needed. All he required was a weapon, some phony documents and a passable disguise. D.B. Cooper had shown him the rest.

Getting the gun was easy. A local pool hall hustler, Walter Petlikowski, provided a .45 rifle, and McNally cut ten inches off the barrel. The weapon fit comfortably inside a black attaché case with a wig and smoke bombs. Petlikowski, in turn, signed on as an accomplice in exchange for $50,000.

In the fall and winter of 1972, McNally charted a tour of Midwest cities, hitting Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis and Kansas City. He settled on St. Louis' Lambert Airport — it had the worst security, McNally says — and made two more trips to the airport with Petlikowski to prepare for the one-way flight.

On the morning of June 23, a Friday, Petlikowski dropped McNally at the main terminal. Petlikowski had changed his mind about participating in the hijacking directly, but he'd still agreed to act as chauffeur for half his original fee. McNally, briefcase in hand, bid his accomplice farewell and boarded Flight 119 destined for Tulsa, Oklahoma.

McNally encountered no metal detectors on his way to the flight. His ticket, purchased with forged Navy discharge papers, identified him as "Robert Wilson."

Less than 30 minutes before landing in Tulsa, McNally excused himself from his seat three rows from the rear of the plane and walked to the lavatory. When he emerged, he was wearing a shaggy brown wig and sunglasses and wielding a rifle. He handed a note to a startled stewardess.

A few minutes later, the captain's voice came over the intercom:

"Ladies and gentleman. We have a passenger who needs to return to St. Louis."

McNally followed D.B. Cooper's example to the letter, though he added a key embellishment: McNally demanded more than twice Cooper's ransom, asking for $500,000. He also requested another $2,000 in small bills, most of which he gifted to the stewardesses as a tip for their compliance.

Around 4 p.m., Flight 119 returned to St. Louis and came to a stop on a runway on the far edge of the airfield. McNally made his demands known. He claimed to control the detonator to a bomb somewhere on the plane, and that any attempts at resistance would be met with gunfire.

Over the next hour, a flurry of negotiations and counter-negotiations played out between the hijacker — who relayed all messages to the cockpit via stewardesses — and FBI agents on the scene. Eventually, McNally permitted 80 hostages to leave the plane by way of the plane's inflatable emergency slide.

But raising a half-million dollars on a Friday evening was no easy task. It could take hours. So, after refueling, McNally directed Flight 119's crew and the fourteen remaining hostages to ready themselves for takeoff. Back in the air, the plane traced circles above St. Louis. At one point, McNally allowed the pilot to redirect the plane to Fort Worth, Texas, based on reports that the money could be collected there much faster. That report turned out to be premature, and the plane instead turned back to St. Louis, where bank and airline officials were still scrambling to put together the ransom.

It was after 9 p.m. when their efforts succeeded. Flight 119 made its second landing on a Lambert runway. Now, McNally relayed three additional demands: He needed a shovel, flight goggles, five parachutes and two harnesses.

The money was delivered in two packages: a heavy airmail bag and a small wrapped parcel. However, despite his preparations, McNally struggled to figure out how to buckle the parachute harness. So he added an additional request: for someone to show him how to put the thing on.

When the "instructor" (actually an undercover FBI agent) came aboard, McNally watched from a distance of several feet, rifle at the ready in case of ambush. The instructor/FBI agent made no move to disarm McNally, and after his quick lesson, left the aircraft unharmed.

It was just after midnight, and the plan seemed to be chugging along perfectly. McNally released thirteen more hostages, leaving under his control one hostage, two stewardesses and the flight crew.

TV and radio stations were already broadcasting the unfolding drama across the country. From behind the rectangular glass facade of the main Lambert terminal, throngs of passengers watched as a tanker truck refueled Flight 119, readying the plane for its fourth St. Louis takeoff in the past eight hours.

But nothing could have prepared McNally for the interference of a young Florissant businessman, David Hanley, who was among the bystanders ogling the drama from the terminal.

Hanley did not remain a bystander for long. As the jet taxied down the runway, its massive engines revving in preparation for takeoff, Hanley's 1971 Cadillac Eldorado crashed through the runway's perimeter, battering through a fence at 80 miles per hour on a collision course with Flight 119.

The plane, heavy with fuel, was essentially a bomb with wings. Over the intercom, the captain's voice crackled with panic. "Oh my god, there's a vehicle on the runway!"

Hanley steered the Cadillac into the nose of the plane. Inside, the impact knocked McNally forward in his seat, and the heavy vehicle careened through the nosewheel, coming to a smoldering halt against the landing gear beneath the portside wing. The damage was superficial — the jet fuel did not ignite — but the plane was crippled.

(Interviewed by the Associated Press one year later, Hanley claimed that the crash had wiped all memory of that night, and that he was as mystified by his actions as everybody else: "My mind is a blank from 6 o'clock that night to two weeks later." As for "reports" that he'd left a cocktail lounge near the airport, telling friends he "would shock the world," Hanley denied it. "If I was there then any friends who were with me were a bunch of slucks," he told the AP. "No one has come to me and said, 'David, I was with you that night and this is what you said.'")

An ambulance arrived to take Hanley to a hospital. He'd suffered two broken jaws, broken ribs, a fractured skull and a crushed left arm and ankle — but the only damage McNally cared about had been inflicted on his getaway ride. The aircraft was useless now. McNally relayed an urgent message to the cockpit: "Get me another plane."

It took 90 minutes to bring a second Boeing 727 alongside the disabled airliner. Fearful of FBI snipers, McNally pressed himself between two stewardesses and covered his head with his briefcase until he safely entered the new plane's lowered rear stairs.

The second plane was fueled and ready for takeoff. Along with his civilian hostage, McNally presided over the jet's three-man replacement crew as well as the one remaining stewardesses he'd kept from Flight 119. There was no need for more leverage than that. McNally ordered the plane to leave St. Louis and set a course to Toronto.

Tracing a straight line, the flight path would take the plane over the vicinity of Detroit. In the preceding months, McNally had tried to work out the precise timing of his jump based on the plane's airspeed, but he now worried that the delays had disrupted his calculations. He had originally planned to make his jump shortly after midnight. It was now nearly 4 a.m.

Still, it was time to leave. He stripped off his disguise and buckled the parachute's harness around his arms and legs.

McNally didn't know where he was. From 10,000 feet, the undisturbed whiteness of the clouds below had obliterated any landmark or geographic feature. He wondered if the pilot had betrayed him, and whether he was seeing not clouds but the deep waters of Lake Michigan.

In reality, McNally chose to make his jump too early. The plane was passing above central Indiana, about 150 miles southwest of Detroit.

Having already hijacked two planes that day, getting to the ground should have been the easy part of McNally's plan. He intended to bury the money immediately, leave the area and lay low for a few weeks or months. Then he would return with a shovel.

McNally dropped from the rear stairwell. Without firing a shot, he'd just made more money than he'd ever earn in a lifetime of shoe sales or petty crime.

But riches were not in McNally's future. Gravity saw to that.

McNally landed hard in a barren field, narrowly missing a grove of trees. He had made a mistake, panicked on approach, thrusting his heels into the soil and causing his body to whip backwards into the ground. His head bounced on the soil, leaving him concussed. His vision danced with stars that were not really there.

The money was gone. It had disappeared, eaten by a blanket of clouds in a moment that imprinted itself in McNally's mind like a nightmare. There was nothing he could do. He didn't even know where he was; the lack of discernible landmarks on the ground made triangulation useless. Of the $502,000 he'd had in his hands, all he had now was $300 that he'd pocketed before the jump.

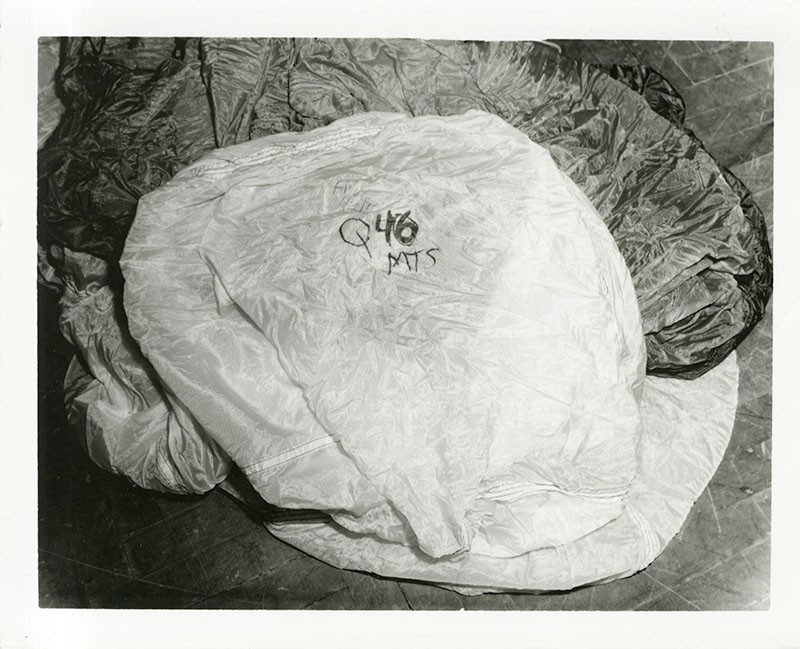

McNally peeled himself off the ground. Around him, the sound of dogs barking echoed through the night. He gathered the parachute and clambered over a barbed wire fence surrounding a thicket of trees. Finding a suitably covered spot, he laid out the parachute and collapsed for two hours.

At dawn, woozy and shivering, he dragged the chute deeper into the woods, where he covered the canvas with leaves and shrubs. He climbed into the parachute's folds as if it was a cocoon and slept until noon.

McNally awoke to helicopter blades thumping overhead. The search parties were already on the move, hoping to sniff out the skyjacker and the loot.

He decided to wait for dusk before moving from the forest's tall canopy. In the meantime, he napped, buried the parachute and cleaned his clothes and shoes as best he could.

Again crossing the barbed-wire fence, McNally walked 500 feet before coming to a gravel two-lane road. In one direction, he perceived a white glow against on the horizon, possibly a city or town. He began trudging in that direction, the monotony broken only by a few cars with Indiana license plates passing by.

An hour and a half later, one car stopped short about a quarter-mile down the road. In the driver's seat was Richard Blair, the police chief of Peru, Indiana. Chief Blair had been driving back to Peru with his wife, and the sight of a lone pedestrian on the road so late at night tugged his interest.

McNally introduced himself as Patrick McNally (his older brother's name) and displayed a Michigan driver's license (a forgery) that corroborated the ID. Though McNally's two credit cards were issued to a "J. McNally," he explained to the chief that he had borrowed the cards — with permission — from his brother.

The chief asked McNally what he was doing out on a country road after 9 p.m.

McNally claimed he had recently traveled to Peru from Detroit on a mission to retrieve his brother from a nearby farm. Alas, McNally continued, his brother had gotten drunk earlier that night and beaten the snot out of him, leaving McNally in this sorry state.

McNally's eyes and cheeks were heavily bruised, his chin was gashed open and he sported several cuts on his forehead. He really did look like he'd taken a beating. Chief Blair offered a lift to Peru, and McNally gladly took him up on it.

Before climbing into the car, McNally quickly slid the handgun from his pocket and tossed it to the side of the road.

("He did not frisk me," McNally would later recall. "If the chief had said anything about patting me down, I would have pulled out this pistol from my right pocket, cocked it and said, 'You'll search nothing.' He and his wife would probably have been killed at that point.")

On the drive to town, Blair warned McNally that it was a bad time to be alone on the road, what with so much traffic speeding back and forth. Hadn't he seen the news? Search parties were scouring the area for a hijacker and a bag of money. McNally answered vaguely in the affirmative, and thanked the chief for saving him the long walk and potential hassle. Blair dropped McNally off at the Peru Motor Lodge, across the street from police headquarters.

It was late, and McNally hadn't tasted food in more than 24 hours. He also hadn't had a chance to look in a mirror. Sitting down for a burger in a nearby bar, he felt the eyes of the other patrons evaluating him from all angles. He wasn't losing his mind to paranoia. In the bar's bathroom, McNally stared in shock at his bruised and puffy reflection. No wonder he was getting weird looks.

McNally returned to the motor lodge and bought a room for the night. The elderly desk clerk accepted his explanation about the mismatched driver's license and credit cards, but she couldn't help but notice the condition of his face.

"You aren't that skyjacker, are you?" she asked.

McNally laughed it off as a joke. "No," he said. The hijacker, he added, was probably a long way off by now.

Using the payphone in the lobby, McNally tried calling an accomplice in Detroit — a fellow hustler to whom McNally had confided the hijacking plan. Hitchhiking from Peru was out of the question; he needed someone to extract him from this hellhole. But there was no answer, so McNally returned to his room to watch TV coverage of the unfolding manhunt. A sketch artist had provided a composite portrait based on witness statements; it flashed on screen, showing a culprit with shaggy hair and aviator sunglasses.

On Sunday, McNally paid for another day in the motel, and made another call to Detroit. Still no answer. He was getting worried: Along with the bruised hijacker, the motel also served as lodging for a half-dozen FBI agents who were in the process of hunting him down. On his way downstairs, McNally passed two agents walking to a different floor; they were oblivious now, McNally thought, but how long could that last? He really had to get out of Peru.

By Monday, in desperation, McNally phoned his chauffeur, Walter Petlikowski.

"I thought you were dead," said Petlikowski.

By now, both had seen the latest breaking news on the search for the hijacker — the bag of money had been recovered in a bean field. The find was made by an elderly farmer, who, perhaps naively, had chosen to report the bag's contents to the authorities rather than keep it for himself. (The farmer's selfless act would later be enshrined in the Guinness Book of World Records as the most cash ever returned to its owner.)

By the time Petlikowski arrived in Peru the next day and the two men took off, the motel was swarming with FBI agents — who by now had picked up McNally's scent. A search party had discovered the handgun he'd hastily deposited on the side of the country road. The FBI knew the hijacker was nearby.

McNally was already dreaming of his next hijacking. If he could take one plane, he could do it again, he told Petlikowski. He was thinking of hitting the airport in Indianapolis.

But there would be no second chance.

By the time McNally returned to Detroit, FBI agents were already staking out his home and awaiting an arrest warrant. Investigators had linked the forged "Robert Wilson" Navy discharge papers to McNally's actual Navy records. And in Detroit, two of McNally's criminal confidants had immediately ratted him out to the feds.

Six days after leaping from a plane and losing a fortune, McNally was arrested outside his home without incident. He was charged with air piracy, which at the time carried a potential death sentence, and held on a $100,000 bond. Not long afterwards, Petlikowski turned himself in as well.

In a turn of good luck for McNally, the U.S. Supreme Court had recently instituted a moratorium on the death penalty. After a quick trial in 1972, McNally was found guilty and given a more humane punishment: a life sentence, which at the time meant just 30 years in prison.

On a summer evening in 2016, McNally nudges a black-and-white cat off his coffee table and lights the first in a long chain of cheap cigars. The smoke billows in the cramped, shotgun apartment. Lying on a threadbare sofa, facing a television playing the news on mute, McNally kicks his feet up on the coffee table.

"Nobody knows my real history," he says. "These neighbors and stuff, they don't know what I'm about, where I came from. They don't know what I'm capable of doing."

After his conviction for the hijacking, McNally decided he wouldn't go down without a fight. He appealed, arguing that FBI agents had illegally searched his home while gathering evidence for the 1972 criminal trial. But his argument failed to sway a judge. When the appeal was denied in 1974, McNally concluded that the courts had been corrupted, and he resolved to free himself by any means necessary.

"I immediately got into escape mode," he says.

In Leavenworth, McNally met the perfect escape partner, a hijacker of some renown. Garrett Brock Trapnell was serving a life sentence for commandeering a TWA flight over Chicago about five months before McNally's exploits in St. Louis. Armed with a .45 pistol smuggled inside a plaster arm cast, Trapnell was ultimately shot and apprehended by FBI agents after landing in New York City.

But Trapnell was more than a hijacker. A highly successful manipulator, he had left a trail of bank robberies across Canada in the mid-1960s, and he became famous for exploiting the legal defense of "innocent by insanity." Upon capture, Trapnell would present symptoms of schizophrenia or multiple personality disorder, committing to the role until a judge granted admittance to a mental hospital instead of prison. Time and again, Trapnell was either released upon "recovery" from his bout of madness, or he simply escaped.

McNally and Trapnell were obvious allies.

"At one point, we made a commitment to each other," McNally remembers. "If I ever got out, I would skyjack a plane to get him out. Or, he would skyjack a plane to get me out."

Before the two could plan an escape from Leavenworth, however, McNally was thrown into a series of high security cells owing to his repeated run-ins with guards. The two men didn't see each other again until 1977, when McNally was transferred to the U.S. Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, the country's first "supermax" prison, dedicated to housing the country's most dangerous criminals. McNally and Trapnell found themselves sharing the same cellblock.

One afternoon in February 1978, Trapnell stopped by McNally's cell and knocked politely on the bars. McNally waved him in. In careful whispers, Trapnell sketched out an escape plan that was elegant, crazy and ethically vile. McNally loved it.

Decades later, McNally looks back on the plan with regret.

"It makes us look like monsters," he says. "We destroyed a family."

Trapnell's offer was simple: "How would you like to leave this place in a helicopter?"

After McNally listened to the details, the two set their minds to refining the plan's moving pieces: First, an outside accomplice would hijack a helicopter at gunpoint and force its pilot to fly to Marion, where Trapnell and McNally would be waiting in a designated spot. From there, they could hijack a plane at the nearby airfield in Perryville, Missouri. The next step could be improvised from there.

The key to the plan was Barbara Oswald. A 43-year-old former Army staff sergeant who had served as an air-traffic controller in a helicopter squadron, she happened to be in love with Trapnell.

Even behind bars, Trapnell maintained an air of celebrity, which only increased after the publication of a biography in 1976. The book, The Fox Is Crazy Too, was anything but a scholarly tome. A lengthy subtitle touted its epic contents: "The true story of Garrett Trapnell, Adventurer, Skyjacker, Bank Robber, Con Man, Lover."

The book had fallen into Oswald's hands. In its pages, Trapnell was presented as a tragic figure, a modern-day pirate who lived life freely and made fools of psychiatrists and prosecutors across North America. Oswald was smitten.

She wrote to Trapnell in prison, and she was rewarded with a flood of love letters. So strong was her passion that Oswald convinced prison officials to place her on Trapnell's approved list of visitors, and soon she was regularly visiting the object of her infatuation. On a few occasions, Oswald even brought her two teenage daughters along for the trip.

It was only a matter of months before Trapnell asked Oswald to help him escape. In letters, he promised her a new life on a 2,000-acre planation he owned in Australia. He sent her photos of a palatial estate where they could live together, happily ever after.

Of course, Trapnell owned no plantation in Australia. And Oswald would never find that happily ever after with Trapnell — or, as it turned out, anyone else.

In McNally and Trapnell's preparations, Oswald represented a tool to be used and abandoned at the earliest opportunity. She wasn't part of Trapnell's post-escape plan, which encompassed robbing a handful of banks with the assistance of McNally and the third member of the escape crew, a convicted bank robber named Kenny Johnson.

Shortly after 6 p.m. on May 24, 1978, the trio of inmates shuffled around the recreation yard alongside a couple hundred prisoners. The day was hot, and many of the inmates were shirtless and wearing shorts.

McNally sweated under a jacket, heavy fatigues and boots. He watched the sky, and waited.

When the red-and-white helicopter made its first pass south, several thousand feet above the prison, McNally signaled to Trapnell and Johnson that they should get ready to run.

Minutes later, the muffled thump of rotors became a sharp whine as the helicopter crested the treetops south of the prison. Guards were already scrambling to arm themselves, and the three inmates had just moments to take advantage of the confusion.

Trapnell, McNally and Johnson made their move, dashing to a restricted area between two housing units, coming to a yard just big enough for a helicopter to land. Trapnell laid out a bright gold jacket to catch the pilot's eye, while McNally jumped and waved his arms as the helicopter tilted and wobbled above the prison.

But instead of landing in the yard, the helicopter settled next to the prison's administration building, located behind several layers of fencing. The whine of the rotors abruptly fell silent, and a thin figure in a blue flight suit leapt from the pilot-side door. There was no sign of Oswald.

Something had gone terribly wrong, but there was no time to figure out what. Trapnell lay down in the grass, seemingly catatonic and unresponsive to McNally's urging — to run the hell out of there.

McNally and Johnson attempted to flee the scene, sneak over a roof and slip back into the recreation yard, hoping to disappear into the mass of hooting prisoners watching the commotion. However, by now every guard was on high alert, either rushing to the helicopter or searching the prison grounds for potential escapees.

Minutes later, McNally and Johnson were spotted on the prison building's roof and apprehended.

Trapnell, the escape's mastermind, didn't move an inch from where he'd collapsed in the yard. A guard would later report that upon discovering the prone inmate, he told Trapnell that he'd been lucky. "You would have been blown away," the guard said.

"I knew it was a set-up," Trapnell spat back. "Was that their helicopter, or mine?"

Inside the helicopter, Oswald's body lay slumped against the cabin's rear seat. She had been shot in the head, spattering blood throughout the cabin and across the helicopter's doors. Bullets had smashed a ragged hole through the side passenger window.

In her final hours, Oswald had tried her best to fulfill her lover's instructions.

She'd reserved the helicopter several days prior, and called the charter company's office around noon to confirm her flight with pilot Allen Barklage. Oswald had posed as a St. Louis businesswoman curious about the condition of some flooded properties in Cape Girardeau. With Oswald in the rear passenger seat, Barklage took off from a downtown St. Louis heliport around 5:30 p.m.

After 30 minutes of flying, Oswald tore off Barklage's headset and put a gun to the pilot's temple. Barklage tried to talk her out of it, but she was adamant: She ordered him to fly east, following a chart to the location where they would rescue three inmates being housed at the U.S. penitentiary in Marion.

But as Barklage made his first pass over the prison at 5,000 feet, he noted the imposing towers and armed guards. A Vietnam veteran and former combat pilot, he considered the likely possibility that those guards would shoot an escaping helicopter out of the sky. He had no intention of dying that day.

As Barklage brought the helicopter around again for the second and final pass over the prison, he informed Oswald that helicopter doors were difficult to handle, and that she was better off opening them now to save time. As Oswald struggled with door, she shifted the gun to her left hand and took her finger off the trigger.

Seeing his chance, Barklage took his hands off the controls and snatched at Oswald's pistol. The two struggled as the unpiloted craft pitched sickeningly through the air above the prison yard. According to Barklage, the fight lasted only ten or fifteen seconds.

When he'd finally wrested the pistol from her grip, Barklage later testified, Oswald had reached for a bag beneath her seat. She told him, "It doesn't make a difference. I've got another one here."

Barklage pulled the trigger five times, spraying broken glass and blood inside the cabin. Oswald fell back, motionless, and Barklage regained control of the wildly pitching helicopter.

When armed guards approached Barklage on the ground, the pilot was nearly incoherent. "I killed her," Barklage ranted, one guard would later report.

"I have been hijacked," Barklage said, over and over. "I have killed and we need an ambulance."

Trapnell and McNally weren't finished with the Oswald family.

The daring escape attempt had drawn national news coverage, and there seemed little doubt that the inmates would be hit with harsh sentences. But as the failed escape crew prepared their defenses — each faced charges for attempted escape, air piracy and kidnapping — Trapnell once again demonstrated his skill for undermining the legal system.

Trapnell decided to represent himself in court, and in so doing, received privileges reserved for attorneys. For one, he was able to arrange unsupervised interviews with defense witnesses. One of those witnesses was Barbara's grieving sixteen-year-old daughter, Robin.

The death of her mother had left Robin depressed and at the point of suicide, details she confided to Trapnell.

"I felt sorry for Robin," Trapnell recalled years later during an interview for a short-lived '90s crime anthology series, FBI: The Untold Stories. "The things she was telling me, I felt a responsibility. I was the one who caused her mother's death. At the same time, I wanted to get out of prison."

Trapnell came to McNally with a new plan: He had seduced Robin, and now the teenager had agreed to finish the job her mother started. Robin would hijack a plane and demand Trapnell's release. As before, Trapnell promised McNally could come along for the ride.

Just days before the trial's conclusion, Kenny Johnson, the third escapee, pleaded guilty to lesser charges for attempted escape. McNally and Trapnell felt no such compunction, and the two arrived in good spirits to the verdict hearing on December 21, 1978.

Trapnell had gotten word to Robin Oswald the night before: She would hijack a TWA flight out of Louisville on its way to Kansas City. In her purse, she'd smuggle a roll of duct tape, some wires and three railroad flares.

It was McNally who'd insisted that Robin be outfitted with a fake bomb. The teenager was unstable, he told Trapnell, and he didn't trust her to handle a pistol, let alone an explosive that could take down a plane full of people. Trapnell agreed.

It was 10 a.m. when Robin, seated in the back of the flight on its way to Kansas City, announced the hijacking and rerouted the plane to Williamson County Airport near Marion. A passenger later reported that her demands amounted to a simple, repeated statement: "I want Garrett."

The judge presiding over Trapnell and McNally's trial ordered the jury immediately sequestered, to keep them away from TVs and radios blaring the prejudicial news updates. But Robin Oswald's hijacking attempt only put a temporary stop to the proceedings. After a lunch break, McNally and Trapnell chain-smoked in a holding cell, fully expecting to be called any minute to Williamson County Airport.

The call never came. After nine hours, Robin Oswald surrendered to FBI agents, who recovered the fake bomb and took the teen into custody.

That evening, a jury returned identical verdicts against McNally and Trapnell: guilty on all counts.

McNally was given another life sentence for air piracy, 75 years for kidnapping, and five years each on charges of attempted escape and conspiracy. The years were added consecutively to his life sentence from 1972. After the conviction, McNally's release date was set for the distant year of 2082.

But McNally had escape skills of his own. Arguing on appeal, McNally and his lawyers raised the issue of news reports covering Kenny Johnson's guilty plea before the trial. Surely coverage had prejudiced the jury against McNally and Trapnell.

In 1980, the U.S. Court of Appeals issued a decision that went even further than McNally had hoped. Not only did the judges rule that the trial court erred in not properly examining jury members for bias related to the news reports of Johnson's guilty plea, but the appellate panel actually acquitted McNally on two of the most serious charges — air piracy and kidnapping. Although there was ample evidence to prove McNally's participation in the escape plot, the judges wrote, nothing tangible linked him directly to Barbara Oswald, the plan to hijack the helicopter or the kidnapping of Allen Barklage.

For her part in attempting to free Trapnell and McNally, Robin Oswald was tried as a juvenile and reportedly released after a short sentence. Considering Trapnell was already facing more than a century of jail time for his previous hijacking and bank robberies, prosecutors chose not to charge him for manipulating the teen girl.

Trapnell would never again attempt an escape. In 1993, he died behind bars of smoking-related emphysema.

McNally had no reason to expect a different fate. By the dawn of the 21st century, he'd given up hope of appealing his 1973 conviction for air piracy or reversing his life sentence. He wasn't a fighter anymore, just an old con moving through a series of concrete rooms and hard beds.

McNally resigned himself to the inevitable. He waited for death.

By 2009, McNally decided that he'd had enough parole hearings to last a lifetime. No more, he told his case manager. Each previous hearing — about a half-dozen throughout the last three decades — had ended with the parole board restating the obvious: McNally's past crimes made him a risk to the public.

But after a miscommunication with a case manager, McNally was nevertheless roused on the morning of July 18, 2009, and told that he was expected at a parole hearing the next day. The inmate grumbled, but an order was an order.

The meeting seemed normal enough. The board quizzed him about his record and his activities in prison. By now, McNally had collected about 30 years of generally good behavior. Like Trapnell, McNally had been affected by the 1978 caper and its sobering aftermath. He wrote to his mother about changing her will. "Don't leave me anything," he told her. "I'm never going to get out of prison."

Yet McNally left the parole hearing in a state of dumbfounded bliss, and he walked back to his cell, grinning ear to ear. Against all expectations, he'd been given a release date. The board had evaluated his 37 years in prison and deemed him capable of handling parole.

Six months later, on January 27, 2010, McNally walked out of the federal prison in Atwater, California, and hopped on a Greyhound bus. He initially requested to be settled in Tennessee to live with an old prison buddy, but that plan had been denied. McNally had no interest in returning to his estranged family in Michigan.

So McNally bought a ticket to St. Louis, the scene of his 1972 hijacking.

"I had no intentions, really, of staying in St. Louis," he admits. "I had planned to go on the lam, rip off some banks, get the vaults, get all the money, so forth and so on."

On the long bus ride, he split his attention between looking out the windows and the fact that people on the bus were making phone calls by holding plastic rectangles to their ears.

Yet he somehow never got around to riding off into the sunset as a bank robber. Instead, he found that he quite enjoys civilian life. With the aid of a reentry program affiliated with the Archdiocese of St. Louis, he was placed in the south city apartment where he resides to this day, paying his own rent and caring for a fluctuating number of cats. He watches a lot of Netflix, especially true crime shows that sometimes feature his old prison acquaintances.

These days, McNally is still reconciling his law-abiding life with the conman who resides in his heart. He's been burned multiple times on get-rich-quick schemes, from buying penny stocks to chasing fictitious fortunes promised by email scammers. His attempts to open wholesale businesses selling jewelry, knives and wristwatches each folded in quick succession. And although he purchased 1,000 lottery tickets before the drawing date, McNally failed to win a $1.6 billion Powerball jackpot in 2016.

On a summer afternoon, a rickety air conditioning unit rattles in the window of McNally's second-floor apartment as the old hijacker pads his way to a desk in his living room.

"Check this out," he says, and retrieves a shiny metal sphere, about two inches in diameter. He holds it up to his eye.

"It thought it was a ball bearing, for big machinery, but there's a bell inside of it," McNally says. He shakes the bauble for a few seconds, producing a mad chorus of jingles. "I don't know what it is," laughs the former skyjacker, "but when I saw that, I said I got to have it."

This is not the existence McNally envisioned for himself as he clung to the stairwell of a Boeing 727 all those years ago. He risked it all, experienced an amazing adventure, and in the process lost everything. Once, he had dreamed of riches. Now, the fact that his kitchen is stocked with groceries and beer seems like a miracle.

"I've come further than most people would reach," he says. "I never thought I would get out of prison. Very few people have had my opportunity."

McNally drags on a cigar. He says he wants to "rehabilitate" the memory of Barbara Oswald, a woman whose only crime, in his mind, was wanting a better life for herself. She, too, had risked everything.

"It's tragic," McNally says. "That woman was driven to her death, just because some phony monsters were intent on getting out of prison under any circumstances."

And now, McNally is the only monster left. Trapnell died alone and incarcerated. Kenny Johnson, the third member of the 1978 escape team, also expired in prison more than ten years ago. Allen Barklage, the hero pilot who foiled their escape, died in a helicopter crash in 1998.

"There's nobody else," McNally says. "I'm the last of the people who know the facts."

After what McNally believed was an ill-fated meeting with his parole supervisor, there was nothing to do but go back to his life on parole, complete with random inspections, restrictions on his movements and the looming possibility that, any day, a single misstep could land him back in prison again.

"The nature of this crime" — the parole officer's testimony echoed in McNally's mind. The meeting had seemed to confirm his beliefs about the criminal justice system, those lessons he'd learned in a series of courtrooms and, later, at the hands of prison guards: Justice was a thing you had to take, by physical force or legal fight, not something granted by a board of bureaucrats. McNally had even begun the process of handwriting a lawsuit targeting the federal parole commission and his parole officer, whom he planned to accuse of violating his rights and conspiring illegally to keep him on parole. Never mind if it was true. When the law bites you, you bite back.

McNally's good fortune, however, knocks on his apartment door on the afternoon of October 4. Shirtless and wearing a worn pair of jeans, McNally welcomes in his parole officer, the very same guy who broke his heart at the August hearing.

But this is no regular checkup.

The parole officer, Tim, hands McNally a single sheet of paper.

"I have some good news," Tim says. "You're off parole."

McNally's face breaks into a smile.

"Oh no," he jokes. "I'm disappointed. I need to have you come over here at least once a month, I need to see you. I don't get enough visitors." The two men laugh, and after a few more pleasantries, Tim leaves McNally to consider his future.

It's a heady feeling, freedom. McNally can travel whenever the mood strikes. He can live anywhere and associate with anyone if he wants to. Or he can remain in St. Louis, playing with his cats and reliving memories of crimes past.

McNally hasn't set foot on a plane since 1972. Even now, he's too paranoid about Homeland Security agents and terrorist watchlists to actually buy a ticket. But if you find yourself in Lambert airport, you may spot a thin, white-haired man with a light smirk on his face, watching the security lines and rows of shoeless travelers hefting suitcases through metal detectors.

Someday, Martin McNally allows, he just might fly again.

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]