PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE MISSOURI HISTORY MUSEUM

Elizabeth Wohlman's police file photo, taken in 1861. Text adapted from Captured and Exposed: The First Police Rogues’ Gallery in America, by Shayne Davidson.

Shayne Davidson has always spent a lot of time among old photographs and records. But when she happened across an especially mysterious portrait several years ago, her longtime interests in history and genealogy grew into something more.

The image — a woman who lived in Belleville, Illinois, in 1861, featured in Charles van Ravenswaay's history of early St. Louis — wasn’t a happy one. In fact, the expression on the subject’s face evoked anger and fear.

“She didn’t look like anyone I had ever seen in a mid-nineteenth century photo,” says Davidson. “I was intrigued by her, and I wanted to know why someone had made the portrait of her.”

See also: 20 Old-Timey St. Louis Mug Shots and the Stories Behind Them

That question eventually led Davidson to the Missouri History Museum’s Library and Research Center, where she examined the original ambrotype up close.

“Mrs. Wohlman, Shop Lifter, 29 years of age,” the script on the back of the photo began. It made mention of the woman’s brown hair, gray eyes and German background — a detail that deepened Davidson’s curiosity. Her own great-great-grandmother, also born in Germany, had been a newcomer to St. Louis around the same time.

Davidson soon found herself combing through newspapers, court and prison records, and city directories to learn more. Piece by piece, the story behind Elizabeth Wohlman’s troubled face became visible: She’d been accused of attempting to steal gold lockets from a jewelry store along the riverfront and would serve ten months in the Missouri State Penitentiary. Meanwhile, three other individuals arrested alongside her — each more established in the region than Wohlman, who had arrived in the U.S. just two years prior — would go free.

But Davidson’s research surrounding the Wohlman portrait was only the beginning. Nearly 200 additional photographs round out the museum’s St. Louis Rogues’ Gallery Collection, and Davidson has since managed to bring dozens of untold stories and long-forgotten faces to light in her new e-book Captured and Exposed: The First Police Rogues’ Gallery in America (Missouri History Museum Press, 2017).

All taken between 1857 and 1867, the photos were originally commissioned and displayed by the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department as a way to identify people suspected of committing crimes. As obvious a tactic as that may seem today, there was nothing else like it in the U.S. at the time.

“That’s what my research uncovered,” Davidson confirms, “that it was the first gallery started by a police department.”

Captured and Exposed presents these early mug shots — carefully preserved in archival envelopes since the 1950s — in their full color and with as much context as possible over the course of 300 zoom-friendly pages.

The photos have sparked interest sporadically over the decades. In 1891, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat announced the discovery of hundreds of rogues' gallery photos, which even then were considered extremely fascinating and old. And some of the mug shots, Davidson notes, probably made an appearance as part of the police department's educational exhibition at the 1904 World's Fair. But they've never before been examined and gathered together in such an exhaustive and readable way.

Along with suspected shoplifters such as Wohlman, there are counterfeiters, pickpockets and even a likely wife murderer in the mix. And their appearances vary as much as their alleged crimes.

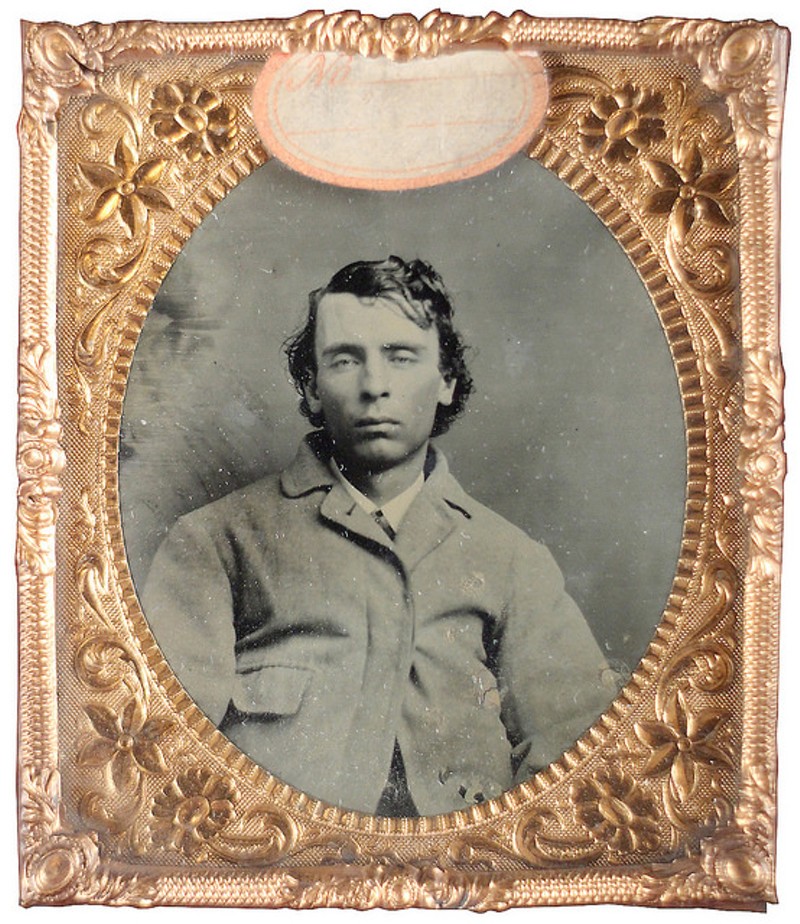

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE MISSOURI HISTORY MUSEUM

Dave Marshal, a suspected "moll buzzer," or thief who pickpockets or steals women's purses. Text adapted from Captured and Exposed: The First Police Rogues’ Gallery in America by Shayne Davidson.

James Manley, a teenager facing charges of assault and battery, looks at the camera vacantly. Worn garments hang heavily on his young frame. Dave Marshal, suspected of “picking ladies’ pockets on streetcars,” appears dazed or deeply bored. Yet dashing New York native Chas Jamison in his “unfashionably large” bowtie seems positively self-assured — perhaps with good reason, Davidson notes in her narrative, as she never found mention of a conviction in his case.

Notably absent from the collection are people of color. Davidson says she isn’t sure why, but guesses that the department simply “may not have bothered.” Also striking among the surviving gallery photos is the predominance of Irish and German immigrants, including Wohlman.

With renewed turbulence around issues such as immigration and police reform in the U.S., Davidson sees some lessons for today.

“It can teach us how, depending on the time period, we target different people,” says the author. “We target different groups and we discriminate against them.”

A native of St. Louis, Davidson left for college at eighteen and now resides in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she makes a living in the field of medical illustration. But her maternal roots continue to draw her back to her birthplace, and she says she has lots more exploring to do. As challenging as the Captured and Exposed project proved to be, it’s obvious that Davidson — a trained artist and vintage photography enthusiast — relishes the hunt.

She compares it to the thrill of spotting a seashell on a vast shore. “I loved looking at the photos,” she says, “and the thing I enjoyed the most was when I actually found something out about someone."

Later this month Davidson will return to St. Louis to discuss the new e-book, which is available in the iBooks Store and for Kindle on Amazon. The event is set for 7 p.m. July 20 in the Missouri History Museum's Lee Auditorium.

See also: 20 Old-Timey St. Louis Mug Shots and the Stories Behind Them