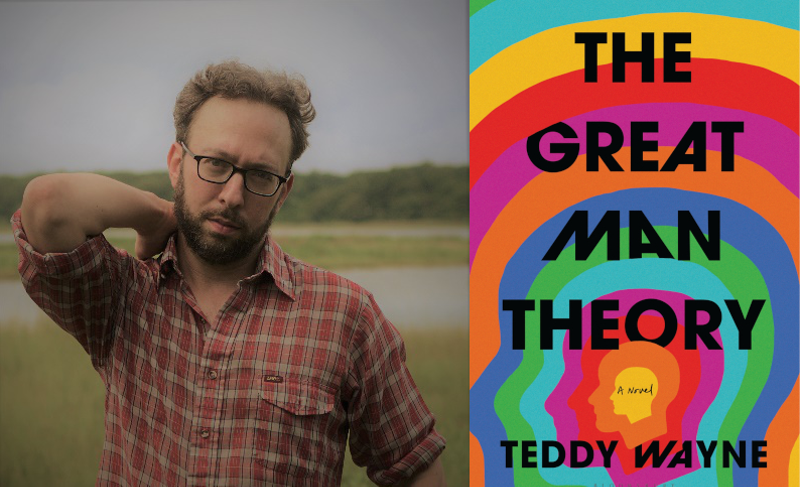

The protagonist of Teddy Wayne's The Great Man Theory could be described as a total sad sack.

At the start, he's a mildly successful, if self-righteous, college lecturer with a contract to complete his first full-length book, The Luddite Manifesto: How the Age of Screens Is a Fatal Distraction. Within five pages of The Great Man Theory, though, Paul's been demoted, his salary halved.

He moves in with his mother. Once there, he finds she's become enthralled by a right-wing talk show akin to Fox News and the devotee of the unnamed, but Trump-like, president. It's here that Wayne introduces Thomas Carlyle's great man theory, for which the novel is named.

"Certain strong, virtuous, and courageous individuals are the ones who shape history," fictional TV host Colin Mackey says in veneration of the political figure.

Paul is not a great man. He aspires otherwise, but by the end of Wayne's novel, he's completely devolved.

A big stress point for Paul is losing his space. In a moment of parallelism, when I connect with Wayne on the book's launch date, July 12, he's also displaced.

"We're sort of between apartments," Wayne says. "We lost our lease at the end of June and have yet to get a new place, and so we're in limbo and bouncing around different places."

A native New Yorker (Yonkers, Riverdale, the Bronx and now Brooklyn, kind of), Wayne found his way to St. Louis in 2005 to attend Washington University's MFA program. He'd wanted to be a writer since third grade, but got serious about the pursuit at the end of high school.

He'd write screenplays and dabble in fiction. Then, after college, he wrote a novel that led to an agent and graduate school — but was never published.

"Thank God it [was] not. It was not good," he says. "[It was] vaguely autobiographical, but the autobiography wasn't interesting enough to work with. Then the deviations from it weren't well written enough to make it compelling — so the worst of all worlds."

WashU did right by Wayne. In addition to turning out what would become his first published novel, Kapitoil, he developed a close-knit writer cohort and stayed after graduating to teach and to continue to haunt Joe's Cafe, with its popcorn, music and fake brook. "To date, my favorite night-life location," he says.

After a year, as his group disbanded and left town, Wayne returned to New York for "the high rents and the breakneck stress of it," he jokes. "And I did want to make my life here ultimately."

In the years subsequent, Wayne published five novels, including The Love Song of Johnny Valentine (2013), Loner (2016) and Apartment (2020), and has been a frequent contributor to publications such as New Yorker and McSweeney's.

Aside from some teaching at the 92nd Street Y, Wayne makes his living as a full-time writer, mostly writing fiction, though he also does screenwriting.

"[With fiction] you can make use of everything you've ever thought of or felt or learned," he says. "It's this wonderful form that encapsulates the entirety of your being in a way that not every other art form, at least that I'm capable of working with, permits."

The story of how The Great Man Theory came to be stretches back to summer 2019. Wayne wrote a novel that he thought was great. But neither his agent nor his wife agreed. At first he was wounded but then quickly had a new idea for a novel about a man outraged by a Trump-like administration and right-wing disinformation.

"But then to make it ultimately not so much about the optics of his ire, which feels easy," Wayne says, "[and] instead turn it inward and make it about the kind of person who is himself obsessed with these people and organizations ... and the nature of his anger."

Paul is a convincing, and mostly humorous, portrait of a certain kind of Gen X, East Coast, white lefty who's excluded from the contemporary left. He's aware that he's not doing well and that there's increasingly less space for him in the world as he fails as a professor and as a father to his 11-year-old daughter.

Though that all sounds incredibly depressing, Wayne lightens the book with deft use of satire.

"This book needed to have comedy throughout or else it would just be, you know, kind of unbearable to read," he says, pointing to a moment where Paul pulls out his DVDs and old-school taste in movies when hosting his daughter's sleepover birthday party. "I knew moments like that were ripe for comedy to undercut the sadness of this guy."

Though Wayne has often turned to comedy (see McSweeney's), he says he's a bit exhausted with the form. Having young children will do that, but it's also a reflection of the world's increasing darkness.

"Does it actually move any needles?" he asks.

Overall, Wayne tries to focus less on his work's impact and more on his craft.

"I think all I could ask for is to be satisfied with the body of work [I] produced," he says. "And to not hopefully care as much about what impact it made on others during the time [it was] coming out."