Five actors curl around a makeshift bar on a recent Tuesday, rehearsing a scene for the Black Rep's season-opening show. Two of the characters are off-shift factory workers, and as they drink, they heckle the bartender after he nonchalantly brings up NAFTA and suggests their jobs will soon be moved to Mexico.

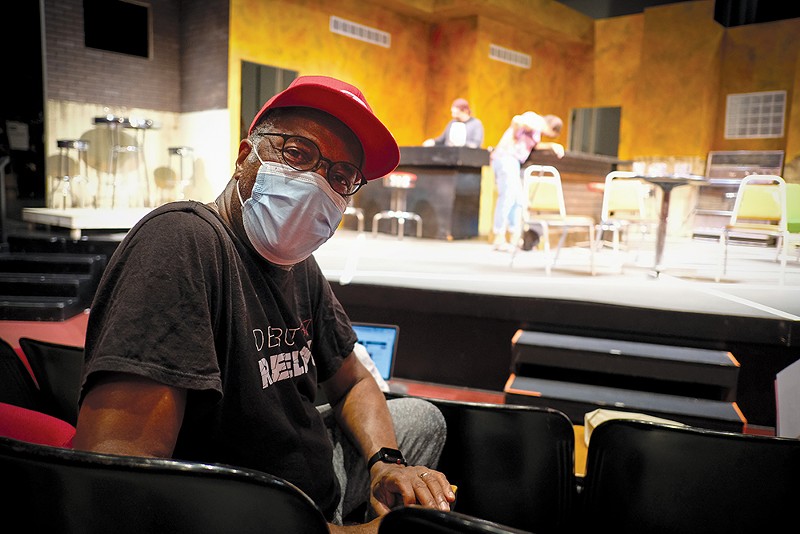

Ron Himes, the theater company's founder and producing director, briefly interrupts to make a suggestion and then sets them to work again.

"Take it from 'You're an asshole,'" Himes says.

"Which one?" they ask.

Everyone laughs and continues on seamlessly.

The scene is from Sweat, the first play in the Black Rep's 45th season. It's an in-person show premiering Wednesday, September 8, at Edison Theater on the campus of Washington University. The play, written by Lynn Nottage, centers around a group of friends who work together on a factory floor in Reading, Pennsylvania, in the years 2000 through 2008.

"The factory is in the midst of negotiations, where they're trying to cut back on the workers' salaries and benefits, and the workers are pushing back against management, not willing to accept the demands that are being made upon them," Himes says. "It's a play that deals with race, immigration, economics and working-class people."

Actor Amy Loui plays Tracey, a lifelong union member whose father and grandfather worked in the factory and whose son now does, too. As with all her characters, Loui has spent the past few weeks connecting to the history that comes with Tracey.

"She's got several onion layers, and they do get peeled back during the course of the show, so you do see little glimpses of what's behind her, what makes her tick, what she cares about — that sort of thing," Loui says in an interview.

And while Tracey is fictional, and Sweat is set across the country in what now feels like a different era, there are parallels between the world of upheaval described by playwright Nottage and the tumult of today, even down to challenges faced by the Black Rep and its staff and performers. The pandemic forced the theater company to cancel plans for in-person shows last season, and the performers and crews turned instead to a run of virtual programming. The company returns to the theater this season under strict guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Wash U. Those include mandatory masking for audience members. Actors and crew members are required to be vaccinated and wear masks during rehearsal time.

"We've never really canceled a production," Himes says. "We've maybe lost a performance, but never a whole run of a production, so [last year] was quite different. There's never been a time like the past fifteen months."

The pandemic hit theaters particularly hard, and thousands across the country closed at least temporarily when a packed house suddenly became a hazard instead of an accomplishment. And Loui is one of the actors who has suffered the consequences.

"It's been a long, hard out," Loui says. "And I know we're not alone. There are entire segments of the population who have been shut down and can't do what they've been trained to do, what they love to do."

Loui says theater is centered around being in community together. "If you think about it, painters could keep going," she says. "Sculptors and musicians could keep going. Even when we'd try to do something through Zoom, there was always a disconnect."

Shifting online was not ideal, but it helped them survive. The scramble is far from over. And like the characters in Sweat, Loui and actors around the country have experienced massive changes with their union, Actors' Equity Association. It started in March of 2020, when theater companies first started closing their doors and actors' contracts fell through. For Loui, her first concern was not being able to qualify for her union's insurance plan.

"Pre-COVID, you had to earn a certain number of contract weeks within a twelve-month period to qualify for health insurance," Loui says. "Once you had thirteen weeks of contract work, you were covered for six months. If you earn eighteen weeks of contract work, they cover you for a year."

Loui had signed two contracts at the beginning of 2020, both of which fell through when theaters closed, no longer counting towards the requirement for health insurance. Luckily, she had done enough contract work from the year prior to maintain her health care, but that wasn't the case for many actors.

Still, the health insurance wasn't what concerned Loui the most. For her, and many other actors, the biggest concern is with changes being made by the Actors' Equity Association in regard to its membership qualifications. Recently, AEA updated its policy to one called "Open Access," where the previously rigorous and prestigious membership qualifications are no longer in place. Now, all stage managers or actors need only to have worked in one professional theater production to qualify.

To explain the situation, Loui references the necessity of the workers' union in Sweat.

"Being a member of the mechanic's union was not only a sign of professionalism, but it was a sign of the quality of the work you were getting from these people," she says.

It's similar to the actors' union, she says.

"For us, the companies that have committed to equity contracts, like the Black Rep, treat our work with value," Loui says. "It's a standard of quality in the performances, but it also means that they're supporting the actors as a livelihood."

With this new union policy, Loui worries her membership in the union will be of less value, and the credentials she has worked to achieve throughout her career will be watered down. AEA's explanation is that the union is working to provide accessibility and benefits to traditionally marginalized groups.

"The reason they're doing it is because they need the dues," Loui says. "We'll see how much the union gets pushed back, because there are a lot of people who are really upset about it. On the other hand, you also think, 'Well, how is it going to survive?'"

If the reputation of the union does weaken from this change in membership policy, Loui believes equity theater companies — those committed to paying their actors — will feel less of a responsibility in maintaining that relationship. By becoming non-equity companies, theaters would save money, but at a cost to actors.

She has faith in the Black Rep's commitment to being an equity theater, but she worries about others. The economic forces are largely out of the control of Loui and other workers, just as they are for the characters in Sweat.

For now, Loui and fellow union members can only wait for the cascading effects of the pandemic to settle, hoping to maintain their careers as best as possible.

"It's still changing," she says. "Even though things are opening and it's seeming more normal, things are still changing."

Sweat

Written by Lynn Nottage. Directed by Ron Himes. Presented by The Black Rep through September 26 at the Edison Theatre at Washington University (6465 Forsyth Boulevard; www.theblackrep.org). Tickets are $20 to $50.