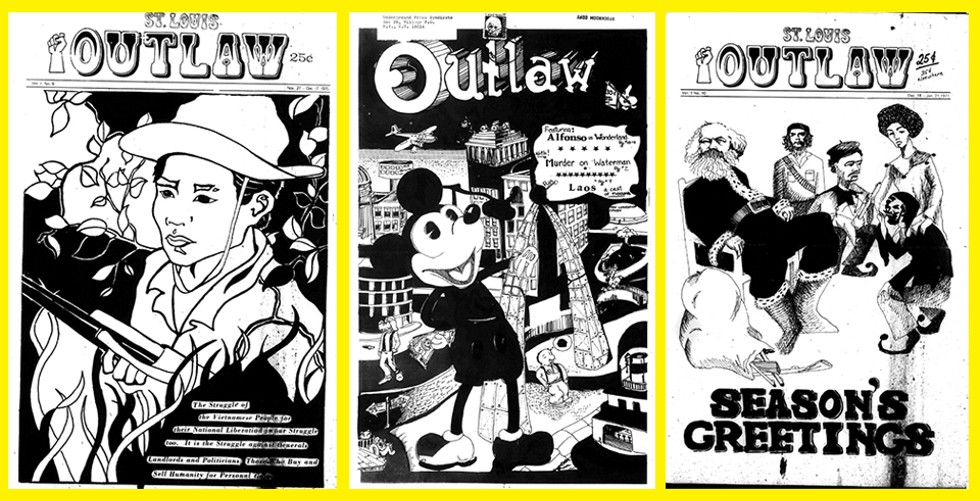

Trolling through newspaper archives for the good stuff can take months or years. The quirky, the weird, the offbeat is always buried in the backlog, in the rubble of a thousand columns on cat parades and debutante balls. That's not the case for the St. Louis Outlaw, a homegrown counterculture magazine running from 1970 to late 1972.

Physical issues of the magazine are hard to come by these days, but local historian Mark Loehrer has gone out of his way to digitize and host 27 issues in a public, free-to-download Dropbox.

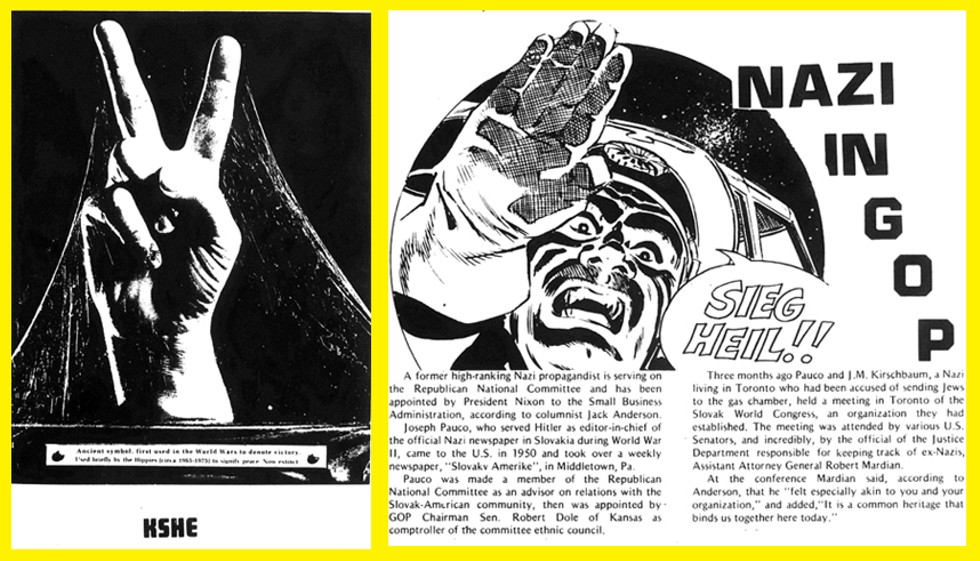

As an affiliate of the Liberation News Service, the Outlaw was a New Left, anti-war underground magazine written and produced by St. Louisans. Liberation News was a press distribution network providing local publications like the Outlaw with national bulletins, photographs and illustrations — especially cool are the drawings from the underground comix movement. R. Crumb cartoons punctuate the Outlaw's columns.

Many contributors were civil rights activists, women's liberationists and members of the Washington University chapter of Students for a Democratic Society. Most of the writing comes from young people trying to find their way through political chaos, war and entrenched bigotry on a local scale. You can find the still-relevant question "Who Controls The Loop" in volume two, number eight, page fourteen.

To get an idea of the political moment that birthed the Outlaw, one month after the first edition ran in April 1970, the National Guard shot four college students at Kent State. They were guilty of protesting the Vietnam War. One day later, on May 5, 1970, St. Louis protesters torched the ROTC building on the Wash U campus.

One of the Outlaw editors, Devereux Kennedy, served as Wash U's student assembly president, and was questioned in the aftermath of the ROTC building fire. Kennedy was a member of the W.E.B. DuBois Society and SDS while the FBI conducted illegal monitoring through COINTELPRO. In the first volume of the Outlaw, page seven, Kennedy's "Chicago Comes to St. Louis" discusses the legal aftermath of the ROTC fire.

Professor George Lipsitz, previously an editor and writer at the Outlaw and now a professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, describes the readership as "long-haired kids hanging out in front of the Magic Market." It was young people who were angry with the dominance of plain white suburban culture, the war in Vietnam and a world teetering on the edge of nuclear annihilation.

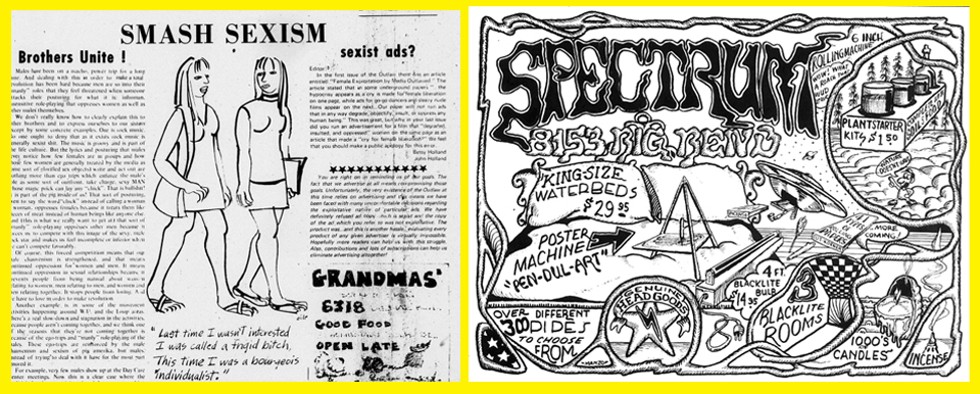

With all the buttoned-up sanctimony of the mainstream media — which constantly lied about Vietnam — the Outlaw searched for alternatives. Nothing was permanent, there was a broad range of subject matter, and would it kill you to crack a joke now and then? One page advocated pissing on Richard Nixon's attorney general, John Mitchell; another features a record review by Marvel Wand; on the next, a female reader calls out a male reviewer of Klute (1971) from the last Outlaw edition: "Why is it so hard for men to admit that the situation of prostitutes are merely the more emphasized side of the lives of many women in this society?"

Some parents of subscribers to the Outlaw found the publication in their mailbox and complained that the post office was delivering degenerate filth. In "SMUT," you can read the editorial response when Manchester, Missouri's Board of Aldermen unofficially banned the Outlaw — volume two, number two, page four. "The minutes of the April 5th Board meeting describe the Outlaw as 'a radical and obscene newspaper,'" it notes. "Alderman Harloe is down on record as opposing 'the sale of pornography and filth.'"

But many found value in an alternative press. The stranglehold on U.S. media made no room for reporting on union busting, the disabled welfare recipients march, women's liberation, abortion rights or the imperative to let one's freak flag fly.

"Nobody could sell out, because no one was buying," Lipsitz says. The Outlaw held open editorial meetings, he recalls — many held in Wash U's Holmes Lounge. In the middle of a discussion during one meeting, a long-haired newcomer's pockets started to squawk — the undercover cop forgot to turn his radio off. "There was obvious surveillance," Lipsitz says.

Many considered Fred Faust the lead editor for the Outlaw; he was a homegrown south-city boy, an Eagle Scout and a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War who sat during the pledge of allegiance at Busch Stadium. Norman Pressman, who was a fellow editor of Washington University's Student Life alongside Faust, tells RFT that Faust once got arrested while selling the Outlaw at the South County Center, but it was on purpose. Faust was trying to produce anti-war documentation. His father was a candy salesman, his mother a secretary for the board of education, and Faust had a draft number — he was not a senator's son.

To get himself in a better draft position, Faust left St. Louis in late 1972 bound for Oakland, California. There, he received an induction notice, but the U.S. attorney in San Francisco wasn't prosecuting every case, and Faust escaped the war.

Naturally, the war in Vietnam occupies many of the Outlaw's pages. Toward the end, "St. Charles GI Says No" runs in volume two, number eleven, page two. The article covers Sgt. Bruce Porter, who became a conscientious objector after working on aircraft like the F-4C Phantom that dropped heavy bombs and napalm on Vietnam.

Pressman says that Faust's leaving St. Louis ultimately ended the Outlaw, but many stories are still relevant. Take, for example, the article "Peabody Coal Crosses the Great Spirit — Navajos Burn Shit in LA" from volume two, number twelve, page seven: Peabody Coal is still headquartered in downtown St. Louis, and polluted huge tracts of Native American holy lands with cancerous strip-mining runoff.

Need some sports commentary from a left perspective? Check out "Get High On SPORTS Not Drugs" from the last page of volume two, number nine.

Wondering how long the cops have wielded a free license for violence against everyday citizens? "Cops Protect Wife Beater" by Sterling and Lucifer is in volume one, number four. "ACTION Report Assails Police" is on page thirteen of volume one, number six. "Workhouse Lets Loose" documents prisoner uprisings in August 1971.

"Women's Bodies: Contraception and Conception" in volume two, number nine, page nine reviews the basics of a woman's reproductive system, The Pill and Margaret Sanger's birth-control movement as a means for achieving a "vigorous, constructive, liberated morality which would prevent the submergence of womanhood into motherhood."

The ads, too, are worth a look: Readers seem to have been obsessed with pants. There's the Lower Half, Foxmoor, Pant Pit, R' Pants. There are bell-bottom jeans, button-fly slacks, flair dress slacks, all kinds of trousers, and plenty of belts, vests and hippie garb from Gypsy Cowboy on North Euclid.

KSHE, "Frantic Free Radio," was especially keen to advertise Gary Bennett, seven to midnight. Akashic Record Shop, Streetside Records, the Melody Mart, the Blew Fuse. Get a java fix at Fleur De Lis or Archduke Coffee House. The Spec Shop sold "unusual eyeglasses" on Laclede, and of course you could pick up the Outlaw at Left Bank Books, which always ran an ad alongside O'Connell's Pub.

Plenty of head shops marketed their goods. Postbellum and the General Store sold Head Foam for unbelievably low prices. The "Dope Scope" column attempted to print information on the available pot in town "as accurately as possible," but some of the most vibrant art in the Outlaw are the ads for the Spectrum head shop. Each is a postcard from a strange psychedelic zone inside a building at 8153 Big Bend.

The Outlaw was, and remains, a valuable lens by which to view the sociopolitical issues of its time from a left perspective. No matter what high school you went to, history class didn't teach the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 or the burning of the ROTC building — but if you were an Outlaw reader, you knew about such events. A lot of radical history in St. Louis is invisible, but Walter Johnson's Broken Heart of America is very close to a people's history of the city. The book is a pathbreaking account of class struggle, racism and emancipatory movements in the Gateway City, from Benton Barracks (now Fairground Park) as the symbolic center of Black freedom during the Civil War, to the unemployment marches of the 1930s, to Percy Green and the ACTION protesters pulling off the Veiled Prophet's hood.

Where the Arch now stands, Johnson notes, there were "places where the poets and the radicals had met and conspired during the years of the Depression." There were clusters of riverfront bars, coffeehouses and squats once known as the Greenwich Village of the West, but Mayor Bernard Dickmann couldn't stand that Black-communist-bohemian alliance which had demonstrated outside (sometimes inside) his office throughout the 1930s. The Outlaw, and the writers and editors who published it, could be seen as spiritual descendents of that alliance. Lipsitz says the Outlaw was a valuable tool for responding to chaos. No matter how much doom, lies and war came along, there were people trying to articulate some alternative in the pages of the Outlaw.

Because of a photocopying quirk, the first issue's guiding statement is a little hard to read. But here's a few quotes from it, written for the Outlaw by the poet Jerry Martien: "We are all Outlaws in the eyes of Amerika — so says a song by the Jefferson Airplane. It seems true.

"Amerika was once an outlaw, but then called Thomas Paine an outlaw for saying so. John Brown was an outlaw because he acted against the slavery of men's bodies and minds. Chief Joseph of the Nez Pierce was an outlaw when he acted on the belief that free people are not to be subjects of the laws of exploitation.

"The outlaws. All the quiet people at the end of their rope, the whimsical old men, the crazy kids, the smashers of tv sets in the night, the refusers of taxes or pills or social workers or school, the underground priest, the makers of pure acid and mind-expanding dope, those who make and live change, you and me, and all such freaks and saints and tragic and comic heroes, the insane or the very sane, us — we may all be outlaws, and Amerika may again be ours."