Years go by. Money runs out. Lawsuits are filed. The film's fortunes soon become entangled with the fall of the Shah of Iran. Reporters who claim that Welles never finishes anything and that the film was never more than a pipe dream begin to gloat.

The story of the film's troubled history is told with wit and depth in They'll Love Me When I'm Dead, a documentary premiering on Netflix and directed by Morgan Neville, of 20 Feet from Stardom and Won't You Be My Neighbor? It debunks many of the Welles myths and places the film within the context of 1970s Hollywood.

And now, almost 50 years since production began, and 33 years since Welles' death, also premiering on Netflix is something called The Other Side of the Wind. The credits say it's an Orson Welles picture — the picture, the movie he shot from 1970 to 1976. But is it?

Of all the efforts to reconstruct or restore Welles' work since his death, this feels most like the real thing. It’s a 98 percent accurate approximation of a film that was meant to be seen as experimental and incomplete. And here's the real surprise: It's a great, crazy, unpredictable film, as innovative and provocative as Welles always said it would be.

The Other Side of the Wind is the story of Jake Hannaford (John Huston), a Hemingwayesque filmmaker of the old school beleaguered by failure and betrayal. His comeback film — also called The Other Side of the Wind — is in danger after his latest discovery walks off the set. His career rests on getting the town's current favorite son and another former protege, Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich playing Peter Bogdanovich), to come to his aid.

The majority of the film is a long semi-improvised party scene filmed in multiple formats and over several years (you can even spot Rich Little, who worked with Welles for three weeks before abandoning the project and being replaced by Bogdanovich), as Hannaford celebrates his 70th birthday at the home of glamorous Dietrich surrogate Zarah Valeska (Lilli Palmer). Hannaford is surrounded by film-school acolytes, New Hollywood celebrities (Dennis Hopper, Claude Chabrol, Paul Mazursky) and a small army of hangers-on and friends (including long-time Mercury Theatre veterans Norman Foster, Mercedes McCambridge and Kane's butler Paul Stewart), all of them functioning as revolving Greek choruses assessing the state of the director's reputation, pocketbook and psyche. (In a moment of panic, an adviser warns, "Five of our best biographers have just gone over to Preminger!")

COURTESY OF NETFLIX

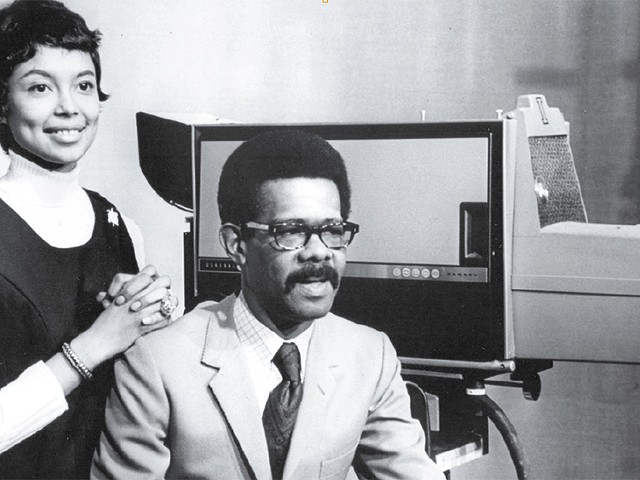

Peter Bogdanovich as himself and John Huston as Jake Hannaford, two directors with a fraught relationship.

Over the course of the evening are boasts, accusations and a few sharp digs at Robert Evans, Pauline Kael, Cybill Shepherd, academia and other Wellesian bête noires, along with a screening of Hannaford's work in progress, a bit of elliptical erotica involving an exotic young woman (Oja Kodar, who co-authored the film) and a muscular bike-boy. (Many commentators see the film-within-a-film as a parody of Antonioni, but its over-the-top combination of Vogue-style poses and Playboy fantasies reminded me more of the soft-core chic of John Derek.)

Set to an excellent jazz score by Michel Legrand, The Other Side of the Wind starts in the middle and never looks back, surveying a film industry in ruins. Decadence is seeping in; as the film crew leaves the set, they pass porno shops and marquees advertising films like I Eat Your Skin. Everything — sexuality, masculinity, loyalty — is questioned. The Old Hollywood of money and power is being challenged by a new philosophy that life and filmmaking are inseparably intertwined. Nearly everyone is carrying a camera, leading to a kind of paranoia crossed with performance anxiety.

There are some familiar Welles trademarks — shadowy settings and severe backlighting, the waves of conflicting voices and contradictory commentaries all circling around a powerful and not entirely savory personality. But there’s also a great deal that breaks away from anything Welles (or any filmmaker) had ever done before. (Dennis Hopper's equally self-destructive 1971 The Last Movie, also getting a belated rediscovery in November, may be the only thing that comes close.) It's argumentative, aggressive, brutally bare and in some places — fireworks! dummy shooting ranges! — just plain crazy.

In the last fifteen years of his life, when he made The Other Side, F for Fake and a few short documentaries about his earlier films, Welles embraced the image of the magician, the man who juggles bits of film through a Moviola and produces images and dreams. Though he bridled at the obstacles that kept his film from completion, he also once said that the duty of an artist was to find the point of maximum discomfort, to search it out. Thirty-three years after his death, the old wizard has pulled off an amazing trick, turning a legendary failure into a brave, raw and inimitable work of genius.