There are two conflicting views of German director Wim Wenders. One is that Wenders, a leading figure of the New German Cinema of the 1970s, is finally getting the recognition he deserves in the United States, thanks to recent retrospectives in New York and Chicago, and the overdue resolution of legal issues that kept many of his best films unavailable for decades. The second is that Wenders is a has-been whose only successful narrative films (Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire) were flukes. (His successful non-fiction films, such as Buena Vista Social Club, Pina and this year's Salt of the Earth are somehow considered irrelevant to this argument.)

Wenders' supporters (I am one) will find little comfort in Every Thing Will Be Fine, a half-hearted meditation on grief or guilt or some other emotion that never quite becomes clear. Written by Norwegian screenwriter Bjørn Olaf Johannessen, it's an incomplete drama in which much is left unsaid or unexplained; resolutions are reached, although it's not clear what they are or how the characters got to them.

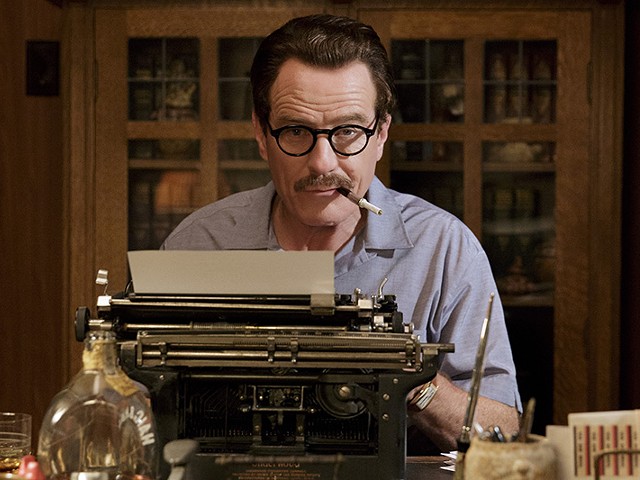

Tomas (James Franco) is a writer, separated from his girlfriend and living in an isolated cabin next to a frozen lake (curiously, neither Tomas nor the film return to this location after the first scene). During a winter storm, he accidentally runs over a small child (an event which mercifully remains offscreen). The remainder of the film is told in intervals running through a subsequent decade as Tomas gradually comes to terms with the incident and establishes brief relationships with the grieving mother (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and the surviving brother of the dead child. Aside from the initial scene of the accident, nearly half the film passes before any of the characters actually meet face to face. For most of the first hour, Wenders simply cuts between brief images of Franco and Gainsbourg going on with their lives, the latter perhaps unintentionally recalling her similar role in Lars von Trier's Antichrist. (Note to filmmakers everywhere: Anything which stirs up memories of Antichrist can't be all good.)

We see Franco and Gainsbourg — mostly thinking rather than speaking — but the film never lets the viewer know just what it is they're thinking about. We see Tomas drinking and getting high as he tries to cope with the incident, only to stop just as abruptly. Wenders and Johannessen are trying to tell a story about bruised psyches, but they're not particularly interested in psychology, so they simply let the characters move around almost randomly, left to heal themselves.

Every Thing Will Be Fine is more sketch than story, but perhaps Wenders is also treating it as more of an experiment than a fully conceived narrative. This is Wenders' second film in 3-D, but even seeing the film in a flat version (as I did), it's clear he is playing with deep focus and using walls and windows to create framing devices and to stress the emotional withdrawal of Tomas and other characters. In the flat version the compositions seem a bit forced, but they don't really detract from the film. But even if we allow for Wenders' efforts to express and reshape the dramatic space, the 3-D compositions are just a tool, not a replacement for the emotional life of his characters.

For all of its occasionally attractive parts, which include the restrained performances (almost too restrained) of Franco and Gainsbourg, Every Thing Will Be Fine sticks to a superficial surface and never finds the emotional depth its characters require.