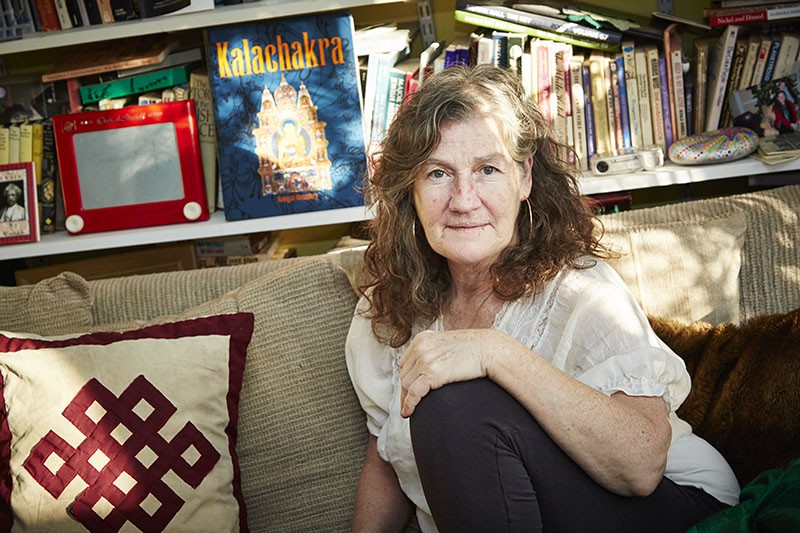

A friend for four decades, Patty Maher has lots of stories about Bob Burkhardt, dating back to his years as one of the key builders of St. Louis nightlife, especially in Soulard. These days, though, Burkhardt has a tendency to change phone numbers. If he doesn't return 25 calls, Maher explains, she has been known to just show up at his doorstep.

And so it goes this November: Maher barreling down Interstate 44, westbound from the city, taking a 30-minute drive in significantly less than that, her Ford F-150 covering ground in leaps and bounds. A green builder by trade and a storyteller by nature, Maher is adept at spinning tales of Burkhardt's days as one of the St. Louis' great pickers.

Maher knows both buildings and the acts of repurposing them, and she's got lots of ideas on how her onetime squeeze, Burkhardt, was able to wed his own free spirit with the more mundane aspects of development.

See also: 27 Incredible Photos of Artists in St. Louis' Gaslight Square

A person can get lucky with one club, hitting on a formula and making it work. But to do it again and again suggests something more elusive — if not quite a gift, at least a talent. Bob Burkhardt, over the span of a couple decades, hit paydirt with every club he opened.

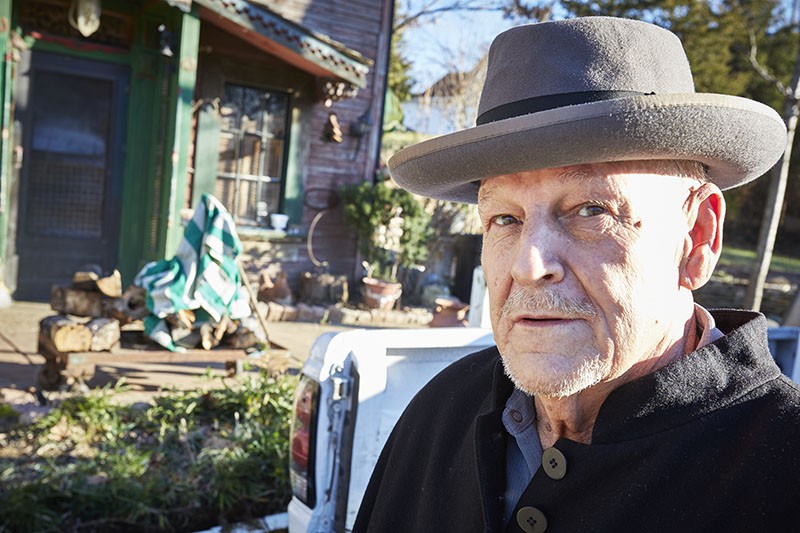

Getting the stories from the source himself means driving to a slip of a town called Crescent, which shares a post office with neighboring Eureka. Save a stint in prison, Burkhardt has lived there for about fifteen years in a house that's part home (for him and daughter Tina) and part antique shop. It's filled with period furniture, display cases of arrow heads, mounted animal heads and other assorted bric-a-brac.

When Maher's first knocks on the door don't bring a host, she just pops in and yells his name. No response.

She changes gears.

"You've got to come around the back first," she decides. "He's got this beautiful limestone grotto."

Sure enough, with the aid of an earth mover and stones culled from this place and that, Burkhardt has crafted a striking stone wall, cropping out of the Missouri clay and centered by a pond created from scratch.

As Maher stares into the wintry water, a sound emerges from behind her, and there he is, an important figure in the history of St. Louis Hip — clad, at this moment, in a white terry-cloth robe and slippers. He invites his uninvited guests in, changes into daywear and subtly asks Maher to head into town for some whiskey and beer.

Then the stories promised by Maher come, spread out over a couple of languid hours; they roll a bit more freely once Maher's completed her run for some smokes and Budweisers and Jameson.

Asked about the grotto, for example, Burkhardt says, "I brought in a Bobcat, a skid loader. I was doing some other stuff around the city, and I was getting these stones. I had a van, but not a plan." He pauses, for effect. "I do plan on having some of that Jameson, though."

So he has another Jameson and they swap more stories, many of them known to a group of St. Louis' bohemian sixty-somethings, but not the general public. Indeed, mention "Bob Burkhardt" in Soulard and most of the kids drinking there have no idea who he is. Time has moved on, and so has St. Louis' bar scene.

But Bob Burkhardt — the man who made St. Louis nightlife what it is today — isn't done yet. In fact, he just might be ready for one more go.

Burkhardt's name, as much as any, is tied to the growth of Soulard as a nightlife destination. He founded both Molly's and the Downstreet Cafe (later Norton's Cafe); they've now merged to form a super-size Molly's.

His work, though, wasn't limited to that one geographic corner of St. Louis. He also tackled projects on Laclede's Landing (Muddy Waters), in south city (via the rock & roll mecca Rusty Springs) and south downtown (both the Broadway Oyster Bar and BB's Jazz, Blues & Soups). For other owners, he constructed and decorated venues, including Christian's and the original Big Daddy's.

For Burkhardt, now 67, the story starts in Dogtown. Born in the same house where he was raised, he went to Southwest and O'Fallon Tech high schools before spending three years in the U.S. Army. He was stationed in Germany, then spent another couple of years just bumming around there, living life.

Back in his hometown in the early 1970s, finally an adult, the building trades called out as a living, and nightlife was his true muse.

In his early twenties, Burkhardt opened Rusty Springs, a 250-capacity club at the southeast corner of Kingshighway and Manchester Avenue. Adapted from a family-style restaurant into a rock & roll room, it was home to groups like Mama's Pride, something of a house band during its pursuit of national stardom.

That club, Burkhardt's first, began his reputation as a man who, along with a partner or two, could get things done.

"He was like the pied piper of bars and clubs," says Mark O'Shaughnessy, who co-founded BB's with Burkhardt. "Or like a Tom Sawyer. He'd be whitewashing the fence. Then, all of a sudden, you're doing the work, and he's having a drink and talking you through it."

Rusty Springs, located at what would today be the entrance to the Grove, is the only club opened by Burkhardt that doesn't still exist as a venue; years after he sold his ownership stake, it became a gay bar, Genesis II, and was later demolished for, of all things, a Jiffy Lube.

Clubs were in Burkhardt's blood from early on, though his parents (Dad a car salesman, Mom a housekeeper) didn't provide the impulse. He had been pulled into the city's heart by the magnet that drew all young people together: Gaslight Square.

"When I was a kid," he says, "I had some good-looking sisters. So I hung out with people who were older. I had an apartment in Gaslight Square when I was a teenager. That space was something else."

At the time, he and his friends worked as busboys at the Flaming Pit, a Clayton Road landmark that did so well, even junior employees were able to afford the rent in the most popular nightclub zone St. Louis has ever known.

Of Gaslight Square, Burkhardt acknowledges, "That's probably where I got my ideas from."

He adds, "It was a neat, as a kid, to be there. I always wanted to be a part of it." "It," he acknowledges, could apply to both the Square and the city's bohemian underbelly in general.

By then, though, Gaslight Square was already in decline, the district's popularity having waned since its early- to mid-1960s heyday. And within a decade, it would be Burkhardt who began steadily building the new nightlife districts that would replace it, one bar at a time, no two ever the same. He even had his own fanbase.

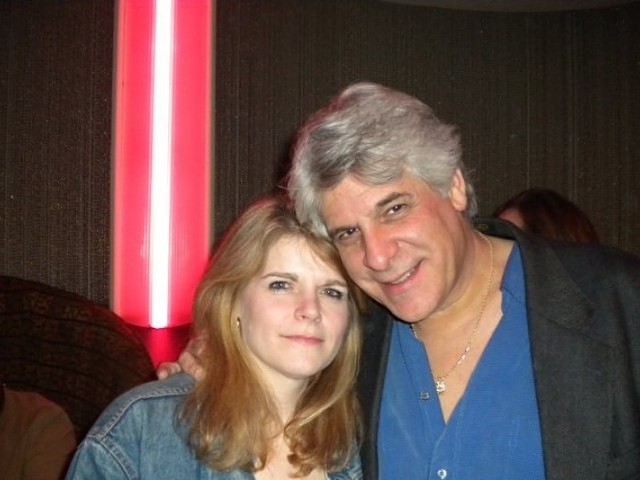

Maher was one of those folks, and now, sitting in Burkhardt's parlor in little Crescent, says that their contemporaries still view him as an inspiration.

"A lot of people tell me that and I don't know why," Burkhardt says.

"Because you are an inspiration."

"I don't know about all that."

And so they keep talking.

Burkhardt's story about the rats goes like this. In the early '70s, as demolition claimed dozens of buildings on downtown's northern edge, countless rats fled from those falling structures. The area, being cleared for the convention center, was no longer hospitable for the rodents, who found themselves up and moving, en masse, toward another edge of downtown: Laclede's Landing.

With Gaslight Square's final mainstay, O'Connell's, relocating to south city in 1972, Burkhardt had settled on the Landing as the next, best location for developing a true nightlife zone.

The realization of that idea came slowly, however. Blossoming into something like a cohesive work/play district by the 1980s, the area's warehouses and industrial spaces were just mismatched, abandoned shells when Burkhardt set his sights on 724 North First Street.

"Doing Muddy Waters, I didn't have enough money to get it open," Burkhardt recalls. "It was just a warehouse before. We opened up with Johnny-on-the-Spots for bathrooms; we had to see the mayor to get permission for that, which would never happen again. That's old school.

"The Landing back then was nothing but warehouses and rats," he reminisces. "A lot of rats. As they took down all of the building for the convention center, there were so many rats that you couldn't believe it. I guess the city came and took for care of it after a couple of months. But at first you'd drive down the street and see ten of 'em, fifteen of 'em, every street."

O'Shaughnessy seconds the story. Of the Landing, he says, "except for the rats on the street and the people shooting off guns, it was pretty much deserted."

Rusty Springs was a smash hit by then, and Muddy Waters would quickly become another destination for rockers, attracting a twenty-something audience and a booking policy that brought in "pretty good acts, like .38 Special, the Outlaws, a band from Chicago called the Flock."

As with his other venues, Burkhardt exited stage right long before the venue shuttered. New owners ran Muddy Waters for decades, until the building flipped over to a chain called Show-Me's Sports Bar & Grill.

But with the Landing now in ascent, Burkhardt's vision turned toward another rundown part of town: Soulard. This time, he approached his projects with reputation that preceded him and a right-hand man.

Burkhardt's creative partner in crime was known to all by the nom de guerre of Johnny Rio. Rio owned a Central West End second-hand store with a legendary Gaslight Square drag queen Lady Charles — and he also formed a symbiotic, colorful relationship with Burkhardt.

"Everything was opened on a shoestring," Burkhardt says. "We never had any money."

Art Dwyer, founding bassist of the Soulard Blues Band and a friend of Burkhardt's since the 1970s, says, "They were a tandem. Bob had a contractor's side to him. And Johnny had the Blind Pig up on Euclid with Lady Charles — a place with antiques, clothes, all kinds of odds and ends. Johnny was really good at accruing merchandise. The two went hand in hand. Did you happen to see BB's when it opened up? It was just like Joe's Cafe, very much like it. So much stuff in there, along with this stage for music. There was stuff just hanging all over the place."

Maher says that Burkhardt "loved Johnny Rio like a brother." Even today, Burkhardt's home is filled with photos and paintings of his late running buddy, who died about a decade ago.

It was Burkhardt and O'Shaughnessy, with a big dollop of Rio, who put together the original BB's. First opened in the late 1970s, it would reopen in the 1990s after a couple of closures and a three-year run as the legendary rock room the Heartbreak Hotel. The long, lean building at 700 South Broadway has seen a lot in its century-plus of life.

Burkhardt remembers that the original BB's was preceded by a low-budget residence called Phil's Hotel Number 2. That's the business that he and his partners initially walked into in 1976, before beginning the process of carving out a blues listening room there. Though Phil's Hotel had a bar intended for the needs of the pensioners living above, it was just a bare-bones tavern. Modern amenities weren't exactly in high supply inside the upper stories, either.

Says O'Shaunghnessy, "It was a flophouse, basically, for over-the-road truck drivers. They'd have a particular girlfriend that they'd shack up with for a week. They'd entertain themselves and have a good ol' time — not that I would've have found that a good time. There wasn't much in the way of food there. It was Landshire sandwiches or it was liquid bread."

But the space's future owners were already hooked.

"We were going in as customers," O'Shaughnessy remembers, "digging the cheap liquor."

"When we first opened BB's, it was a 37-room hotel," Burkhardt says, free-associating. "There was a maid that worked there for 23 years, Vera. It was a hotel, but had the showers and toilets down at the end of the hall, except for rooms 25 and 23. They had toilets in the rooms. There were two hookers who lived and worked there. One of them was Goldie. She had a song that she'd always play on the jukebox..."

It's enough to make Maher emit a loud laugh.

"Bob," she asks, "how do you remember all that?"

"I don't know," he says. "I remember things from when I was a kid. But I don't remember what I did last week."

And sometimes he loses his phone or drops it in a tub of water. And then Maher comes out to check on him. Then days like this happen. Memories flow.

People remember all kinds of different things about Bob Burkhardt.

Wm. Stage, a former long-time Riverfront Times columnist, remembers plenty. For Stage, specific to Burkhardt (and Rio) is the phrase "ain't nothin' but a house party," a catchall that Burkhardt and Rio used to throw back-and-forth with abandon. Burkhardt still uses it today, almost as a punctuation mark.

The poet Lenny Smith, a member of the freewheeling Soulard Culture Squad, remembers a cat (a literal cat, not a hepcat) that used to patrol BB's, keeping its rat population in check. He also remembers that Burkhardt was able to keep tabs on certain things, while others would be left for completion on another day. There was always a good reason, though, why something wasn't finished.

"I asked him once why this one board on the Molly's deck wasn't hammered down," Smith recalls. "And he knew why, and he knew exactly which board."

Tom Burnham remembers certain kindnesses extended as well. As a historian of Soulard's culture, Burnham emailed his recollections of Burkhardt.

The man, Burkhardt, and his then-neighborhood, Soulard, blend effortlessly in Burnham's retelling:

In 1986, Soulard was still a dirt-poor part of town. You could still find livable houses for under $10,000. There were a lot of abandoned properties. Some were occupied by squatters, completely furnished, but heated and lit with kerosene. There were people scraping by in shells just a half-step above being homeless. It was a routine part of life in the neighborhood. If you lived there, you were, by simple proximity, acquainted with some marginally housed people. Some of those folks would come to the shelter at Sts. Peter & Paul when winter was at its harshest.

The shelter at Sts. Peter & Paul was still a seasonal program. It only operated the 151 days between Halloween and April Fool's. It had been subject of an RFT cover story that winter, 'Brother, Can You Spare a Neighborhood.' Some of the early gentrifiers wanted to shut it down. Toward the end of the season, late March, Peter Rosenberg, Ollie Matheus and I had an idea for a little public-relations event. We asked Bob Burkhardt if we could throw a barbecue in his back yard. Invite the shelter residents and folks from the neighborhood for an early spring Sunday afternoon get-together. We thought a little familiarity might alleviate some tension. Bob, familiar with many of the homeless neighbors and always up for a party, was all in.

The day before, the St. Louis Blues Club — only later did it become a 'Society' — threw its first event, a day-long concert at Mississippi Nights, including the very best blues St. Louis could offer at the time: Henry Townsend, James Crutchfield, Tommy Bankhead, Doc Terry, Oliver Sain, the Soulard Blues Band, Tom Hall, Leroy Pierson and many others. Peter, Ollie and I were all present and spreading the word about the barbecue party at Burkhardt's the next day. By noon the next day, most of the musicians, all long-time friends of Bob, began to show up with their instruments. It was a spectacular day.

Those kinds of stories abound. Dwyer, for example, remembers a time when Burkhardt and a few other Soulard wags decided to help him out, carrying 35 sheets of drywall up several flights to Dwyer's third-floor apartment. Along for the ride was Molly, Burkhardt's dog. (The bar in Soulard? No matter what stories circulate today, it's named after Molly the Dog.)

Of Soulard in the 1970s, Dwyer recalls, "Back then, you wondered where everyone came from. I thought I could really be stepping further down into the abyss — it's getting pretty funky down here. All of a sudden, it started filling up and really flowered through the late '70s and '80s. There were weekend-long parties, like down at Ninth and Geyer. People would be there all weekend long — you'd have Johnny Rio on the corner, cooking a whole pig."

And Burkhardt was central to it all — a father to four, a friend to hundreds. He bartended and managed the long-running blues bar the 1860 Saloon and Hardshell Cafe for nine years, even while owning a place across the street. There were always people around, and many, if not all, had his best interests in heart.

If Rio's passing a decade back still weighs on Burkhardt, other challenges have presented themselves in more recent years. Within his circle, there's a fierce sense of protection around him, as folks know that he recently spent time in federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana.

Charged in 2010 with a single felony count of distributing crystal meth, Burkhardt pleaded guilty and was sentenced to five years in prison. He was released from the Terre Haute facility about a year ago, with a chunk of the remaining calendar year spent at a north-city halfway house. He left that space on July 12, and spent the balance of 2015 in tiny Crescent, where he can attack projects on his own time — his ever-expanding grotto, the classic red Gran Torino in the front yard.

It's Burkhardt who initially brings up his time away, by saying, "I got one visitor there, in five years. I didn't like visits. They leave and you're stuck. Prison's not that bad, but who wants to be there, anyway? They make millions from it, that's what it's all about. You've got people in for non-violent crimes who are doing twenty to thirty years, and some people who kill other people are released in five."

As quickly as the topic arises, it recedes. Wistfully, at that.

"I spent five years in prison," he says, dragging at a smoke and sipping at a tiny tumbler of Jameson. "And I did three years in the army. That's eight years that I gave. On Thursdays, I have to go to these group meetings. They've got drop-ins four times a month." He pauses. "I did my time. Now just leave me alone."

He needs time. After all, there's still work to do, including a "readying" of his home in Crescent, where his house, largely hand-built, sits within spitting distance of three golf courses, the Meramec River, deep woods and, just yards from his front door, a heavily traveled railroad track.

He's preparing for a possible move back to St. Louis. After fifteen years on the furthest edges of town, it'd be a proper return for a true city kid.

And maybe, just maybe, a return to the trade that made his name.

"Yeah, I was thinking about buying a place, you know," he says, his voice, as typical, just above a whisper. "I'd like to open a place like the Preservation Hall in New Orleans. Everyone's dying in my age group; it'd be neat to have a place for us. There's one area I like, south of the Arch. It's an area where the old slaughterhouses were. It's an old hotel. It's got an iron door with bullet holes in it and sign that says 'Little Willie's Last Chance.' That's the one."

It's another longshot, this idea, born in an area of the city that, once again, most have abandoned or regarded as hopelessly out of step. In a sense, then, it's a perfect Burkhardt target.

Money might be an issue; for most of us, it's an issue when turning dreams into reality. For him, though, any project is a chance to reject that notion, or at least to fight it.

"I don't really care about money," he says. "I never cared about money. I was in the business because I liked it. I like people. That's the whole trick to being around the entertainment business: If you don't like people, you're in the wrong one."

Running a place long-term might not be in Burkhardt's DNA, but getting one off the ground? That's where he excels.

As O'Shaughnessy says, "He's an artist and he can become bored with his creations after he builds them. But he's like a Bob Cassilly. The dreams and the schemes...they just shine when they have that idea."

Or, as Smith adds, "He designs pretty. He really does."

One fall day the weather is just turning, and Art Dwyer is celebrating a belated birthday at the Broadway Oyster Bar, the onetime Burkhardt's Oyster Bar. At a table in the back, a real mishmash of people are gathered around a series of tables, strung together into something like an elongated pair of figure eights. Here sit bar owners and poets, photographers and illustrators, radio hosts and college administrators, plus those whose jobs aren't known; they simply buzz over to the table and stay. Even with the late-autumn chill and the lack of Mardi Gras, breasts are bared and praises sung.

With his back mildly turned away from the stage, Bob Burkhardt sits. And smokes. And smokes some more. And he takes compliments and greetings from a variety of old friends and, true, a few others meeting him for the first time.

Once, this was his patio, a corner lot that came into being due to an explosion. That kind of thing influences how a bar gets built, and Burkhardt's got plenty of stories of how the Broadway Oyster came to be: It would be offshoot of BB's down the block, born of the time when he was splitting away from that project and, lo! Another building on the same street came open.

From the stage that evening, the band offers more than one invocation of Burkhardt's name. Vocalist Marty Abdullah calls him out more than once, as does Dwyer, while the impeccably dressed Burkhardt takes a couple of spins on the Oyster Bar's infamously uneven, cobblestoned dance floor. Wearing a jacket, two-toned dress shoes, a gold chain and hat, Burkhardt looks splendid, if somewhat uncomfortable with outpouring of goodwill that's coming his way.

He's not been out on the town very often since re-entering the world on July 12, but there have been a few. Like this one. Evenings where old friends show up and curious things happen.

"It's a small world," he figures. "You run into people all over. It's not the first time I've walked into a place and known people. I walked into Terre Haute and knew some people there, too."

For a man who doesn't care about money, there's something that rankles a bit, though. In time, it comes out like this.

"I'd like to stop by Oyster Bar. But I don't wanna pay $10. Do you know what I mean?" he asks. "You know how many times I've walked through the doors of that place? Four thousand times? I'm not the kind of guy to say, 'You know who I am?' I don't play that stuff. I just don't want to...it's not the $10. It's the principle."

Ideally, every club in St. Louis would waive the cover for Burkhardt, no questions asked. There'd be a barstool for him and a Jameson on the rocks and an ashtray, smoking laws be damned. There'd be someone else to coax the stories and a few more someones to listen. There'd be an understanding that his fingers and mind helped shape so much of what's hip here.

Someday, maybe there'll be another Burkhardt bar, built out of a brick skeleton and aided by just enough dollars to open the door.

He'd argue that none of that matters. That even his name and legacy don't matter.

"I'm just an ordinary guy," he says.

But he'd really prefer not to pay that cover.

See also: 27 Incredible Photos of Artists in St. Louis' Gaslight Square