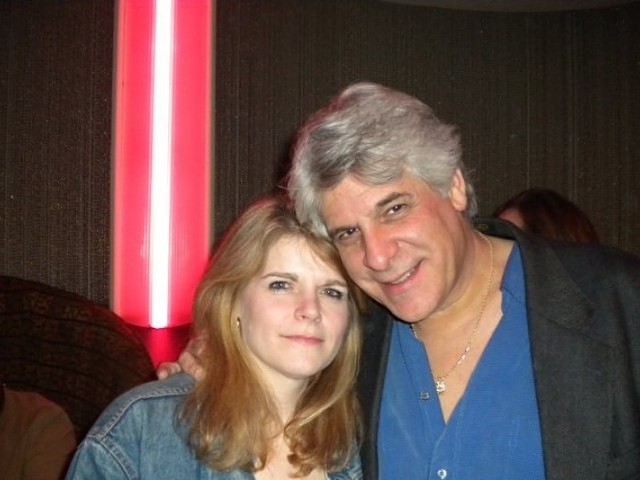

Burkhardt's name, as much as any, is tied to the growth of Soulard as a nightlife destination. He founded both Molly's and the Downstreet Cafe (later Norton's Cafe); they've now merged to form a super-size Molly's.

His work, though, wasn't limited to that one geographic corner of St. Louis. He also tackled projects on Laclede's Landing (Muddy Waters), in south city (via the rock & roll mecca Rusty Springs) and south downtown (both the Broadway Oyster Bar and BB's Jazz, Blues & Soups). For other owners, he constructed and decorated venues, including Christian's and the original Big Daddy's.

For Burkhardt, now 67, the story starts in Dogtown. Born in the same house where he was raised, he went to Southwest and O'Fallon Tech high schools before spending three years in the U.S. Army. He was stationed in Germany, then spent another couple of years just bumming around there, living life.

Back in his hometown in the early 1970s, finally an adult, the building trades called out as a living, and nightlife was his true muse.

In his early twenties, Burkhardt opened Rusty Springs, a 250-capacity club at the southeast corner of Kingshighway and Manchester Avenue. Adapted from a family-style restaurant into a rock & roll room, it was home to groups like Mama's Pride, something of a house band during its pursuit of national stardom.

That club, Burkhardt's first, began his reputation as a man who, along with a partner or two, could get things done.

"He was like the pied piper of bars and clubs," says Mark O'Shaughnessy, who co-founded BB's with Burkhardt. "Or like a Tom Sawyer. He'd be whitewashing the fence. Then, all of a sudden, you're doing the work, and he's having a drink and talking you through it."

Rusty Springs, located at what would today be the entrance to the Grove, is the only club opened by Burkhardt that doesn't still exist as a venue; years after he sold his ownership stake, it became a gay bar, Genesis II, and was later demolished for, of all things, a Jiffy Lube.

Clubs were in Burkhardt's blood from early on, though his parents (Dad a car salesman, Mom a housekeeper) didn't provide the impulse. He had been pulled into the city's heart by the magnet that drew all young people together: Gaslight Square.

"When I was a kid," he says, "I had some good-looking sisters. So I hung out with people who were older. I had an apartment in Gaslight Square when I was a teenager. That space was something else."

At the time, he and his friends worked as busboys at the Flaming Pit, a Clayton Road landmark that did so well, even junior employees were able to afford the rent in the most popular nightclub zone St. Louis has ever known.

Of Gaslight Square, Burkhardt acknowledges, "That's probably where I got my ideas from."

He adds, "It was a neat, as a kid, to be there. I always wanted to be a part of it." "It," he acknowledges, could apply to both the Square and the city's bohemian underbelly in general.

By then, though, Gaslight Square was already in decline, the district's popularity having waned since its early- to mid-1960s heyday. And within a decade, it would be Burkhardt who began steadily building the new nightlife districts that would replace it, one bar at a time, no two ever the same. He even had his own fanbase.

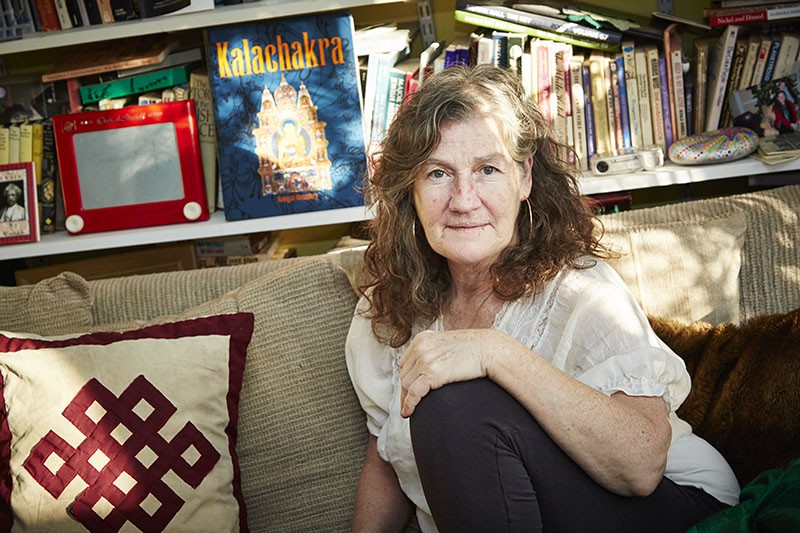

Maher was one of those folks, and now, sitting in Burkhardt's parlor in little Crescent, says that their contemporaries still view him as an inspiration.

"A lot of people tell me that and I don't know why," Burkhardt says.

"Because you are an inspiration."

"I don't know about all that."

And so they keep talking.