Alex Garcia took refuge from federal immigration agents nearly two months ago inside an old brick church in the St. Louis suburb of Maplewood.

He is still there. He may be there for a long time — or maybe a short time. There is really no way to tell. The 36-year-old construction worker is hoping to return home to Poplar Bluff, Missouri, in time for the holidays. Even weeks ago, Thanksgiving had begun to feel like a long shot. But maybe Christmas. Christmas would be wonderful. He, his wife and his five kids get together with his in-laws and eat tamales on Christmas.

It's one of the rituals he has adopted during his thirteen years in the Bootheel. Bow hunting deer in the fall. Fishing with the kids in the summer. And work. Work is all the time. Work is how Garcia, an undocumented immigrant from Honduras, earned the respect of white, blue-collar guys in Butler County, where Donald Trump won 79 percent of the vote.

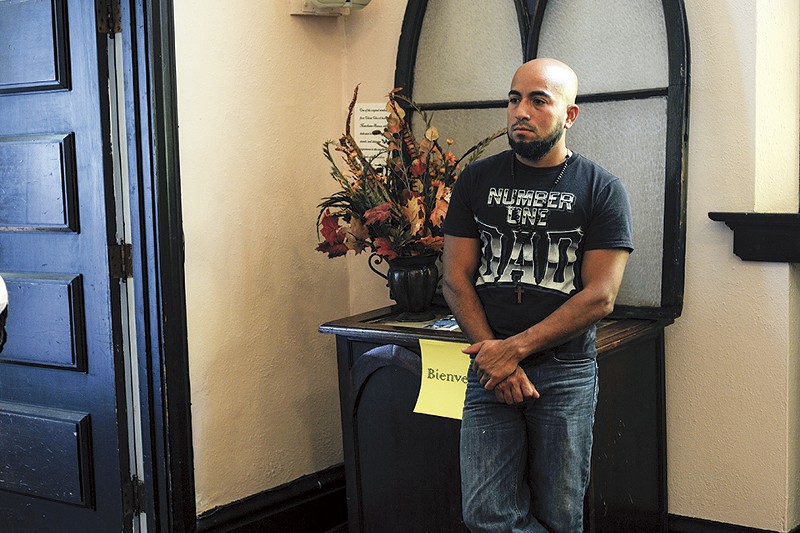

Bald with a bushy beard that sits low along his jaw, Garcia is a quiet force on the job site. Other contractors and business owners describe watching him crawl over roofs or pour concrete all day before he heads off to mow grass on his nights and weekends. They know he has five kids to support, and they respect him for doing it without welfare — which, they are quick to point out, is more than they can say for a lot of their neighbors.

"You need to get rid of about half the people in this town and keep him," says Jamie Tyler, a 38-year-old railroad worker who also runs his own construction company.

There is no guarantee Garcia is coming back to Poplar Bluff. In fact, the odds are not great. After granting him temporary permission in 2015 and 2016 to stay in the country, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials denied his request for 2017. It is part of a new hard-line approach on undocumented immigrants.

The agency notified him of its decision in a letter sent at the end of August. Garcia's wife opened the envelope on her lunch break and called him in a panic. "I was a little panicked, too," Garcia recalls, carefully choosing the English words. "But I was trying to tell myself it was going to be OK — one way or another, everything was going to be fine."

All across the country, undocumented immigrants are getting similar messages from ICE. The agency is under new directives to broaden the scope of its enforcement efforts. Trump, who campaigned on promises to deport all the "bad hombres" from the U.S., issued an executive order in January that expanded the focus from people who are national security threats to virtually anyone who has crossed the border without permission. Even those, like Garcia, who have been previously vetted and granted stays multiple times in the past have been targeted.

Now, his future is uncertain. His wife and kids are American-born citizens. Honduras, which has one of the highest murder rates in the world, is not a realistic option for his family, he says. If he's deported, he will be required to wait ten years before he can be considered for legal re-entry. What happens to his children, Garcia wonders. His youngest is three. His oldest, 12-year-old Ayden, was diagnosed in 2014 with Asperger Syndrome.

"They need me right now," Garcia says, adding later, "They always going to need me."

Unbeknownst to Garcia, a loose network of religious leaders in the metro area had anticipated a situation like his — and they had already begun making plans.

The roots of what is now known as the St. Louis Coalition for Sanctuary started with meetings and discussions in February. Trump's executive order regarding ICE enforcement priorities was barely a month old, and his administration was also making plans to beef up U.S. Border Patrol and phase out Differed Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, the Obama-era policy that granted certain permissions to young undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. by their parents.

"It's laying the foundation for mass deportations," says Sara John of the St. Louis Inter-Faith Committee on Latin America.

Searching for ways to push back, the group began considering sanctuary as a possible option. The concept is thousands of years old and is basically an agreement that law enforcement officers won't barge into a house of worship and start hauling out fugitives. In medieval England, noblemen sometimes took refuge inside churches for weeks at a time while they tried to negotiate with angry lords. A modern-day movement turned toward immigration in the 1980s when thousands of people fled bloody, U.S.-backed civil wars in Central America. Angry that then-President Ronald Reagan was loathe to grant the newcomers status as political refugees, activists and religious leaders set up networks of churches to serve as safe houses.

The Rev. Noel Andersen of Church World Service, which tracks the movement, says the difference between now and the 1980s is that the people taking refuge today are already here, often living and working peacefully in the country for years before they claim sanctuary.

The policy shift under Trump has simultaneously put those people in danger of deportation and sparked new levels of activism in supporters, he says.

"I think that we've seen there's a real increase in the number of people in the country that understand we need DACA, we need a path to citizenship," Andersen says.

Since the election, the number of churches nationwide that have publicly agreed to offer sanctuary has doubled to at least 800, according to Church World Service. There are about 30 known cases across the country of people currently living in sanctuary. Most of them are in cities, such as Denver, that have large populations of undocumented immigrants. None was in Missouri — until this fall.

In September, John learned about Garcia's case. The construction worker's attorney, Nicole Cortés of the MICA Project in St. Louis, works closely with the Inter-Faith Committee on Latin America. She knew John had recently attended a conference to learn more about sanctuary and put the family in touch.

John remembers those first conversations clearly.

"They were terrified at the prospect of him leaving," she says.

Sanctuary is not for everyone. Moving into a church with no end date is an extreme and, at best, temporary solution. John carefully laid out various scenarios.

Garcia and his wife, Carleen Garcia, spent two weeks trying to decide what to do.

"In the beginning, I was against taking sanctuary," Carleen says. "I was against him not doing what they were asking, specifically because I was worried about the repercussions for doing so."

Garcia was worried about drawing negative attention to the kids, and the couple had concerns it could put Carleen in legal jeopardy, too.

"Then one morning I woke up, and I was like, 'What am I doing? Why am I just giving up? Why am I just going to give him to them?'" Carleen says. "What kind of wife would I be if I didn't fight for him?"

Garcia had been ordered to report to ICE by September 21. Instead he moved to an undisclosed safe house and, a couple of days later, Christ Church in Maplewood. He has been there ever since.

Garcia spends his days in the church hunting for projects to keep himself busy — leaky windows to glaze, faded doors to paint, drywall to patch.

Built in the early 1920s by German evangelicals, Christ Church sits on a corner in a shady residential neighborhood of Maplewood. It has become a hive of activity. On any given day, food trucks are parked outside while cooks prep meals in the building's lower-level kitchen. Gardeners tend the last of the summer vegetables in raised beds at the edge of the parking lot, and off hours are filled by twelve-step programs and GED classes.

The Rev. Rebecca Turner, who leads the progressive congregation, was one of the first to say her church would offer Garcia sanctuary.

"If we're going to take seriously following Jesus, then we have to engage with the world," she says.

Weeks later, she does not regret the decision, even if engaging with the world leads to engaging with a powerful arm of the federal government. Legally, ICE agents could show up at any moment, force open the doors and take Garcia away. Sanctuary offers no real protection from the law. But Turner is relying on ICE to follow the agency's written policy that says it won't enter "sensitive" locations, including churches, to make arrests unless there is an emergency.

As an added safeguard, Garcia and his supporters chose to announce their actions publicly, sending out press releases, enlisting politicians and allowing reporters to visit the church. Cortés says if ICE agents do decide to go against their policies and arrest Garcia at the church, they will have to deal with the publicity that comes with it.

"We're not going to let that happen quietly," she says. "If that's happening, we're going to be loud."

Rep. Stacey Newman (D-St. Louis County) is one of the elected officials who have come to Garcia's aid. She says his case is a perfect example of the need for a better path to citizenship, and it would be cruel to deport him simply over a shift in policy.

"This is a real-life situation for Alex and his wife and his five children," she says. "Sending someone back like this is really just out of spite."

Questioned by the Riverfront Times, an ICE official confirms the agency does have plans to deport Garcia, but that agents won't arrest him as long as he stays in the church. They're now locked in a standoff, with Garcia unwilling to go out, and ICE agents unwilling to go in.

A base-level tension hangs over the situation, but most days in the church are low on drama. Garcia might listen to the radio for a bit in his makeshift quarters after waking up. (He regularly tunes in to Sean Hannity, although he concedes the conservative commentator would not approve of his situation: "No, he would not agree.") And then he starts whatever project he has selected for the day. The old church has seen plenty of wear and tear in the past century, and Garcia scans every surface as he makes his way through the building. On a recent morning, he works his way down an interior hallway, scraping, sanding and painting a dozen doors within a few hours. He wears a NUMBER ONE DAD shirt, blue jeans and a wooden rosary that some visitors to the church gave him recently.

Turner has made it clear he is under no obligation to do anything, but he says he cannot just sit around all day. If he thinks about his kids too much, he will start to cry.

"It's hard when the little one says, 'Dad, why you don't go home with us?'" Garcia says.

He was nineteen when he first tried to cross the border from Mexico into the United States. Born Rene Garcia Maldonado, he says he grew up in the countryside of Honduras without electricity. The closest town was a two-hour walk.

Originally, he thought he would make some money up north and come back, but Border Patrol agents caught him shortly after he crossed the Rio Grande. That was in 2000, and a federal immigration judge signed an order expelling him from the U.S. There was not even a hearing.

He tried again around 2004, and this time he did not get caught. He quickly hopped a northbound train, unsure where exactly it was headed. When it dumped him out in Poplar Bluff, he remembers it was raining.

"I got off the train and started walking, seeing what I could find," he says. On his first day, he landed a job as a dishwasher at a Mexican restaurant, where he worked for seven years before going into construction.

In the early days, he says, he still planned to return to Honduras. But he soon began to assimilate into the Poplar Bluff community. He dated a local woman, and they had two boys before the relationship ended. He started dating his wife a decade ago. She also had a son from a previous relationship, and when they got together, they meshed their families together. Now married seven years, they've added another boy and, finally, a girl.

In 2013, Garcia and his wife contacted Cortés to try to get him citizenship.

As Cortés looked into Garcia's case, she soon discovered bad news: The 2000 immigration deportation order was still in effect. A DWI from 2008 was the only mark on his record, but that 2000 expulsion for border crossing effectively killed any chance of obtaining legal status, Cortés says. It did not matter that his wife and kids were all natural-born citizens.

For awhile, everything was still fine. The family did have a scare in 2015. Garcia's sister had also crossed into the United States, and he decided to accompany her to a scheduled immigration check-in at an ICE satellite office in Kansas City. He had originally planned to just stay in the car, but the location seemed a little sketchy so he escorted her.

Cortés says that was a mistake. ICE agents questioned Garcia and eventually identified him from the 2000 order. Before he knew it, he was being detained.

He was locked up for two weeks before Cortés was finally able to persuade ICE officials to grant him a stay of removal. To make her case, she included signatures and letters from hundreds of people as well as medical records for his son, demonstrating the ongoing need for Garcia to remain in the country.

She was able to get another year-long stay using essentially the same argument in 2016, but things had changed when she tried again in 2017. Under Trump, stays are much more rare. Even if they're granted, they tend to be for shorter amounts of time, 30 days or six months as opposed to a year, according to the agency. An ICE official says the recent policy changes and the more sweeping nature of arrests is basically a return to pre-Obama enforcement directives.

There is some truth to that, says former federal prosecutor Javad Khazaeli, but the Trump-era changes go much further than Bush ever did. Now in private practice in St. Louis, Khazaeli worked for the Department of Homeland Security under George W. Bush and Obama. He says prosecutors previously had discretion to go after the most dangerous people. The idea was to focus their limited resources on terrorism and violent crime.

"I'd rather go after the child molester than the 80-year-old Guatemalan grandmother who has no criminal record," he says.

A guy like Garcia would have gotten a look under the old policies, Khazaeli says, but it is unlikely he would have ever become a priority for removal once it was determined he was not a threat.

"What the Trump administration has done has totally changed that," he says. "What I think they're doing is trying to increase their statistics."

After all, it is a lot easier to find and arrest people who are already checking in than to hunt down a gang member living on the fringes.

"The downstream effect of that is now you can't put as many resources to go after people who are actual threats to national security," says Khazaeli, who sent an inquiry to ICE regarding Garcia at Cortés' request. "I think we're significantly less safe because of this."

In the first 100 days after Trump's executive order, ICE arrested more than 41,000 people confirmed or suspected to be in the country illegally, a 38 percent increase over the same period in 2016. That translates into more than 400 arrests every day. And while nearly three-quarters of those arrests are of people with criminal records, the number of those arrested without criminal records is surging.

The proof is in the stats for non-criminal arrests during the first quarter of 2017. Busts spiked to 10,800, more than double the 4,200 recorded the previous year.

None of that is good news for Garcia, who is hoping immigration officials will look beyond his legal status to all the positive things he has done — and the harm his deportation would do to his family. He thinks that should count for something. Whether it will is up to ICE.

All Garcia can do is wait. He spends his days biding his time, trying to be useful, waiting for a reprieve that may never come. He and Carleen have told the two youngest children he is just working at the church. The three older boys know vaguely that his absence has to do with immigration, but they do not fully understand. Garcia does not quite understand it himself. Like anyone without legal status, he always knew there were potential consequences, but considered the possibility remote. He had followed a code over the years to assuage his fears.

"The longer you do good, don't harm nobody, you'll be OK," he told himself.

The Rev. Turner and more than a dozen other clergy members meet on a windy October morning outside of Robert A. Young Federal Building in downtown St. Louis.

Garcia's last, best legal option is to persuade ICE to take a second look at his request to stay in the country on a temporary basis. The trouble is that agency officials have so far refused to even accept the paperwork.

It hasn't been for lack of trying. His wife, backed by a few dozen activists, attempted a month ago to hand-deliver the paperwork, but a clerk at the ICE satellite office turned Carleen away.

The pastors have decided to try again. There will be no march this time, and Carleen is not with them. The plan is for Cortés and Turner to deliver the documents, which include more than 800 signatures of people in favor of Garcia's application. They have kept the group small, enough people to show support but not so many as to give Department of Homeland Security officers a reason to say they're causing a disturbance.

Still, within minutes of their arrival, officers stride over and inform them they cannot congregate on the marble floor of an outdoor courtyard. The group dutifully moves onto the sidewalk, where Turner addresses them. She reiterates that they are not there for civil disobedience, but simply to drop off the paperwork and leave. Eventually, eleven people and a toddler head through the spinning doors of the building.

But when they reach the mouth of the hallway leading to ICE's office, a pair of DHS officers steps in front of them. The office is locked for lunch. No one can accept the documents. "They want me to tell you they won't even answer the door," one says.

Cortés speaks up: "ICE accepts documents here all the time."

They make it to the doorway, but the office behind the glass door is indeed locked when they arrive. The officers tell them they have to go, but the pastors refuse. Eventually, the officers agree to ask the ICE staff if two people can come just far enough in to deliver the papers.

Instead, the officers return with what appears to be a police or security supervisor.

"Any tenant in any federal building has the right to refuse service," the supervisor tells the group.

John is incredulous, pointing out that these are taxpayer-funded government offices. Turner repeats that they just want to deliver the papers. "We are not here for civil disobedience," she says.

"Well, that's what this is," the supervisor replies.

Just as it's getting tense, a manager steps out of a side door and finally agrees to let two people into the office. This seems to satisfy the police for the moment; they disappear down the hallway again.

Cortés leans against the wall and shakes her head as she waits for the door to be unlocked. "Fuckery," she says under her breath. She and Turner are eventually allowed inside.

Through the glass, the clerk can be seen cracking an interior door just wide enough to poke her head out and accept the papers before she ducks back inside. Minutes pass as Cortés and Turner wait for her to return.

As the clergy wait hopefully in the hallway, the officers return yet again. This time, they are adamant: Everyone has to leave.

"It's not me asking," one of the officers says. "I'm telling you, you have to go."

He and the pastors go back and forth. The officer wants to know if everyone is refusing to leave. Worried that arrests are coming, three of the people in the group leave, but the others stay. The officers sighs.

"We'll see what we have to do," he says, before leaving again.

Whatever the police decided, the group will never know. Moments later, Cortés and Turner exit the office. The clerk had stamped their papers and given them a receipt. Turner smiles a huge smile and gives the group two thumbs up. They're euphoric over what is the bureaucratic equivalent of mailing a letter.

"That was incredible," Cortés tells the group. "You guys did that."

Later, an ICE official will tell the RFT that staffers had only locked the office door because it was their lunch break, not to avoid the pastors. However, that does not appear to be true. The times posted on the door say lunch ends at 12:30 p.m., and the group lingered until nearly 1 p.m. Conversely, when the RFT returns on two separate occasions during the posted lunch break, the doors are unlocked.

Three weeks after the hallway showdown, Garcia receives a response from ICE: The agency has denied his request. After all they went through to deliver the documents, it is as if officials did not even read the paperwork, John says. Both the timeline described in ICE's denial letter and the number of Garcia's children are wrong, she says. Not that Garcia's supporters are surprised.

John says they always thought it could take multiple attempts. Now, they are settling in for the long fight ahead.

The drive to Poplar Bluff from Maplewood winds south, rising and falling over the hills for more than 150 miles. It was still summer when Garcia left home in September, but now the leaves have begun to change to bright oranges and reds as fall takes hold.

Benjamin Zuniga, Garcia's father-in-law, has been at work since 4 a.m., splitting time between two job sites along the city's main commercial district.

"Alex is the man every man wants for his daughter," he says. "That will tell you everything."

Built like a jockey, the 56-year-old has a graying mustache, a tape measure on his hip and wire-rimmed glasses. He and Garcia have worked side-by-side nearly every day for the past six years, or at least they did until the trouble with ICE.

Zuniga immigrated to the United States from Mexico at age seventeen. Back then, in the pre-9/11 era, it was much easier to obtain legal residency, he says. He traveled from California to Illinois and met his wife on his first night in Chicago. He first visited the town of Poplar Bluff nearly 30 years ago to work with his father-in-law, who had a contract installing cable TV service. When the contract was over, Zuniga decided to move there for good.

He estimates there were only one or two other Hispanic people there at the time, but like Garcia decades later, he proved himself through work. He took a job at the Tyson plant and switched to construction when he grew tired of chickens. Over the years, Poplar Bluff has become home. He raised his daughter here, and now gets to see his grandchildren grow up here, too. He has a house twenty minutes outside of town and another 35 acres of woods he uses as a hunting camp on the rare days he can get away. It is the kind of middle-class life that has always been the promise of the American Heartland.

Garcia was following the same path, and he worked alongside other men doing the same thing. The only difference is that he remains undocumented.

Jim Bailey, a developer who hired Garcia and Zuniga to overhaul a pair of shopping centers in town, says Garcia had "gotten himself in a pickle" by entering illegally, but he can't see any sense in throwing out a working man who has five kids depending on him.

"You take Alex out of the equation, and you're going to see a mother and five kids on some type of assistance, if not full assistance," he says.

Bailey, Zuniga and a handful of contractors, laborers and business owners feel so strongly about supporting Garcia that they have pooled money to cover his bills during the past two months.

"He's just a good, honest guy that wants to work hard for his family," Bailey says. "That's a very rare thing these days."

Shortly after lunch on a cold, windy day earlier this month, Zuniga drops by what will soon be a new Starbucks to help finish a concrete pad out back. With a population of about 17,200, Poplar Bluff has managed to avoid the decline of other Midwestern towns. In addition to Bailey's two resurrected shopping centers, new buildings are going up on the west end of town near the four-year-old Poplar Bluff Regional Medical Center. A coalition of businessmen is pushing a plan to expand a section of interstate to create a prime Chicago-to-Dallas route that would pass through town.

There's plenty of work, which makes Garcia's absence all the more noticeable.

Near the future Starbucks, Zuniga is met by a host of familiar faces. Everyone on the site knows about the potential deportation.

"Almost puts tears in my eyes, all the things they've done to him," Corbit Barnet, 58, says.

Poplar Bluff is a conservative town, and the men on the crews are about the opposite of bleeding-heart progressives. During a break, 51-year-old Jarrod Lewis jokes about how shocked his daughter's liberal classmates at Saint Louis University law school were when they learned about the AR-15 rifle he gave her as a gift. The story gets a round of laughs.

The Second Amendment might as well be a commandment, but discussions about immigration have become pretty nuanced. There is general agreement that immigrants should come here legally, but they also believe there should also be a better path to citizenship for a guy like Garcia, someone who has worked hard and supported his family.

"He's been living the American Dream, and there's a lot of people who are natural-born citizens that are not taking advantage of the American Dream," Lewis says.

The men commiserate about what they see as the rise of a welfare state, populated by a growing number of able-bodied adults on public assistance. Zuniga similarly sees a laziness in the government's approach. He figures if federal officials would put in the effort to look at Garcia's case, it would be obvious that he's an asset.

"They need to do their homework," he says.

Among the construction crews, this is part of what bugs them the most. They figure arresting Garcia is the easy way out, a way to pump up the number of arrests and deportations without actually going after the trouble-makers. In the end, they look at Garcia's case and see one more example of the working man getting screwed.

"I'm not a Democrat," says Jamie Tyler. "I'm not a liberal. I'm supposed to be a Republican, but I don't know about them anymore. But I know a good guy when I see one."