It was a chilly November evening last year when Melvin Bain, a homeless veteran in his late fifties, had a few bucks in his pocket and figured he'd try to win a few more at Lumière Place Casino.

"I used to be lucky," Bain says. "I'd go in with $2 and come out with $82."

Over the past few years, however, Bain's luck has changed. After losing his job as a cashier at a pizza shop, he fell behind on his child-support payments. One year went by, and, still out of work, Bain was convicted of criminal nonsupport and sentenced to eight months in prison. While he was locked up, his house burned down. Because Bain hadn't been keeping up with his insurance payments for the property, he left prison homeless.

Eventually Bain found his way to an encampment along the St. Louis riverfront — just a few blocks away from the gleaming lights of Lumière. To Bain, it made perfect sense to take a chance on those couple dollars in his pocket. Unfortunately, the casino didn't feel the same way.

"They discovered I was homeless," he says. "And they don't like the homeless around there."

Bain was pushing coins into a slot machine when police officers came up and questioned him. Since Bain didn't have identification on him, he was told he'd have to leave the premises and was given a trespassing warning. A few weeks later Bain returned to the casino with an ID. He says he was again kicked out and issued a trespassing ticket. Around that same time, Bain also picked up a few tickets for panhandling.

He now owed the city of St. Louis $200 in municipal ordinance violations, not including court costs. It was $200 the homeless vet simply didn't have. Still, Bain arrived for each of his court dates and told the judge that he couldn't pay. And each time the judge told him to return at a later date. If Bain failed to do so, the judge would issue a warrant for his arrest.

A similar process unfolds day after day inside the city's municipal court: A recent Tuesday brought traffic hearings. And like Bain, nearly all of those in court this day are black.

"I don't have the funds today, your honor," says a short African American man with a tired look in his eyes and tattered clothes on his back.

"I lost my job. I can't afford it," a young black woman with glasses tells the judge.

A few defendants are able to pay part of their fines, which range from $200 to several hundred dollars. Nobody, though, is able to pay their entire fee at once. And the vast majority can't pay anything. They are given an extension and a new date to reappear in court. If they miss it, a warrant will be made for their arrest.

To date, there are more than 700,000 outstanding warrants for municipal offenses in St. Louis. And when tickets become warrants for the poor, the problems pile up. There's the anxiety that comes from fearing arrest and — ultimately — the arrest itself. Even a few days in jail can cost people their jobs. And losing employment often means that those living on the margins will fall behind in rent and face eviction or homelessness. It's a chain reaction attorney Thomas Harvey sees all the time.

"The municipal court system financially exploits people of little financial means," says Harvey. "It works really well for people who have some money. It doesn't work at all for people who don't. And I don't think [the government knows] how serious of an impact it has outside of the financial part. They don't think about the next step, and the next step, and this sort of domino effect."

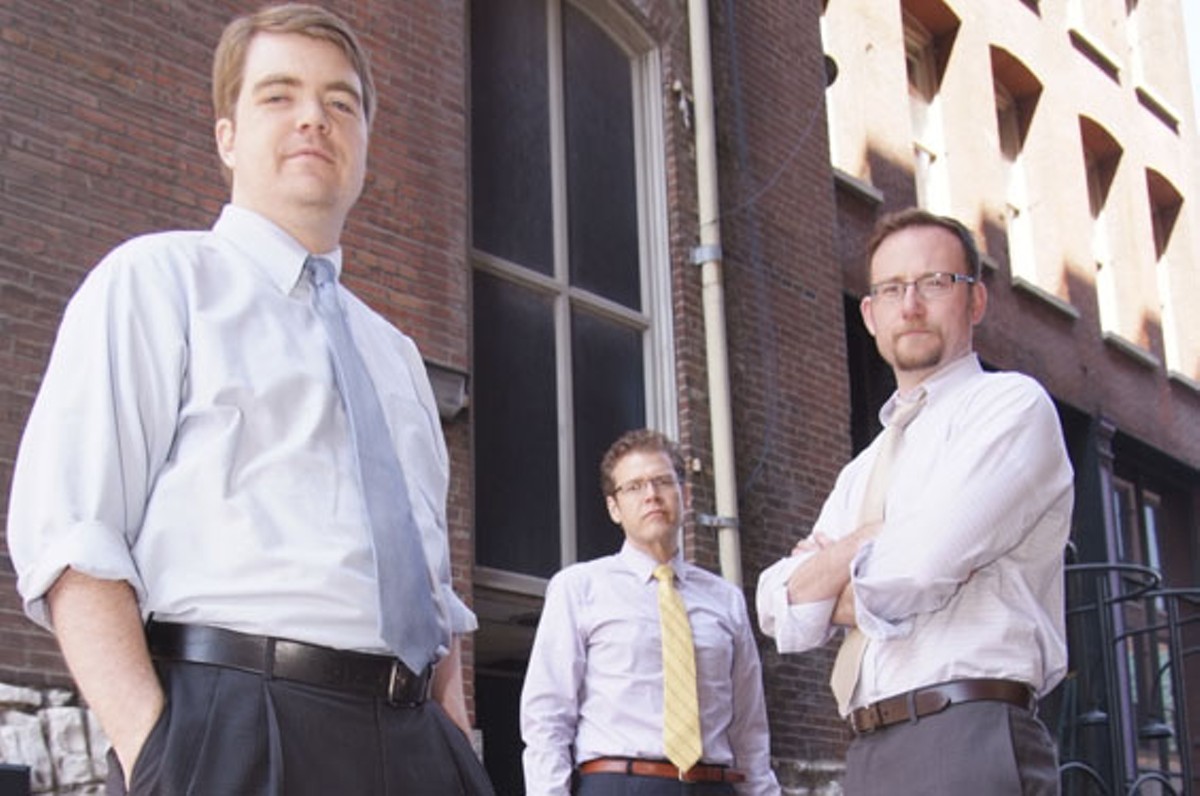

Five years ago Harvey and two law-school buddies — Michael-John Voss and John McAnnar — founded ArchCity Defenders, a nonprofit with a mission to rescue those caught up in this legal morass. But more than just offering legal aid to the indigent, ArchCity Defenders works to help its clients improve their overall lives, be it securing housing, getting drug treatment or finding a job. It's called "holistic advocacy," and it's a growing public-defense philosophy that's getting a shot in St. Louis.

"One of the pillars of holistic advocacy is to try to give people access to services all under one roof," explains Harvey. "And if you can't make them available under one roof, make access to services as easy as possible."

But that's a challenge in St. Louis, especially for a small nonprofit that often finds itself locked in battle with cash-starved governments — governments that have grown dependent on making money off the downtrodden.

ArchCity Defenders has a certain comic-book ring to it. Harvey is aware of this. So, too, is the mother of one of his colleagues. She stitched up a superhero cape and donated it to the office.

"When someone does something outstanding, they get to wear the cape," says Harvey, who had crime-fighting — though not exactly the caped-crusader kind — on his mind when he dreamed up the idea of ArchCity Defenders.

In 2009 Harvey worked as a legal intern at the criminal-defense clinic operated through the Saint Louis University School of Law. Part of his job was to work the intake desk, and it was there that he noticed a problem.

"I saw a lot of poor people who had mental-health problems and substance-abuse problems who weren't getting any of those services while they were waiting in jail to get a lawyer," Harvey says. "On its best day, the public defender gets the person's case dismissed, but that person still needs additional services to get on with his or her life."

It was a wake-up call to the law student. Even with adequate legal assistance, if people didn't get help addressing their underlying issues, they'd likely be back at the intake desk within a few days or weeks.

While Harvey witnessed this problem on the criminal side, his law-school classmates — McAnnar and Voss — were seeing a similar pattern during their internships working in civil law.

"Many municipalities depend on ticket revenue. And when rich people get tickets, they hire a lawyer who gets it turned into a nonmoving violation, and that person pays a larger fine but doesn't get points on their license," says McAnnar.

Voss adds: "And when poor people get tickets, they can't pay, so they go to court six months in a row, make monthly payments, maybe $50 if they have it. But if they miss a payment, a warrant is issued, their fines go up, and that person gets into a hole."

For the three SLU law students, seeing poor people get slapped with fines that inevitably snowballed into other problems made them want to do something. What or how wasn't exactly clear.

Harvey says he got the basic concept for ArchCity Defenders the way most people find things these days. He did a quick Google search of what he wanted to do and came across the name Robin Steinberg.

Steinberg, a New York attorney, founded Bronx Defenders in 1997. Today it is considered the nation's first holistic-defense organization and is part of the New York City public-defense system. If a criminal defendant in the Bronx qualifies for legal aid, they get an attorney from Bronx Defenders. With a large staff of attorneys and social workers (as well as relationships with social-services organizations throughout the city), the agency can then streamline the process of getting its clients the help they need and keep them out of jail for low-level offenses.

"This model doesn't cost more per case than a defender here in New York that's doing the work in a very traditional way," Steinberg says. "It's just a matter of how you allocate your money, where the resources go and how creative you become in terms of figuring out ways to harness the resources you need for your client."

Without addressing those needs, whether it's poverty, mental illness and addiction, or heavy-handed policing in poor areas, Steinberg says the cycle will continue and simply increase economic and societal costs.

"Public defenders are the least expensive part of the criminal-justice system. So if you're looking at the system, in any jurisdiction, you need to look at the overreliance on jails and begin to look at alternatives to that," says Steinberg.

A conversation with Steinberg helped Harvey and his law-school friends identify what they wanted to do, but they lacked the money to start it. After graduation, Voss and McAnnar accepted jobs at corporate law firms in St. Louis while Harvey hung his own shingle as a criminal-defense lawyer. Still, they never forgot their idea, and when McAnnar was briefly furloughed from his firm as a result of the recession, he set about getting ArchCity Defenders established as an official nonprofit.

"We took on cases whenever we could," Harvey recalls of those initial days in 2009. "I had more flexibility because I had my own practice, but we all made time. When somebody calls you from jail and they need to get out, you make time."

For nearly three years the three men ran and funded ArchCity Defenders mainly on their own, but they got a little help, too. Volunteer attorneys believed in the mission and offered services. Law students saw it as a great learning opportunity. And Voss' employers at Reinert Weishaar & Associates liked the idea so much that they donated some sleek and stylish office space just off the cobblestone streets of Laclede's Landing.

But it wasn't until 2013 when Mayor Francis Slay ramped up his campaign to end homelessness in St. Louis that ArchCity Defenders was able to fully devote itself to the holistic-defense model.

The mayor's BEACH Project (the Beginning of the End: Abolishing Chronic Homelessness) aims to assist chronically homeless people within St. Louis by providing them jobs and places to live. These people, by definition, have experienced repeated or long-term homelessness and have a disability. They also tend to have legal issues, such as warrants, for which free legal counsel is off-limits or unavailable.

In St. Louis, the federally funded Legal Services of Eastern Missouri can, by law, only assist the poor with civil cases. Meanwhile, the public-defense system can help people with outstanding municipal warrants in theory, but the financial reality makes that impossible to do.

"It's unfortunate because I'd love to handle these people with ordinance violations piling up," says Richard Kroeger, the assistant district defender in St. Louis. "But we are constantly fighting for funding, and that's just enough to effectively represent the clients we have now."

Through a contract with the BEACH Project that began in June 2013, ArchCity Defenders has been able to help fill that gap.

"Getting a person off the streets and into housing, sometimes there are legal barriers for that," says McAnnar. "They might have five warrants out for their arrest for traffic violations, and minor ordinance violations in the municipalities. This all might keep them out of certain housing units and job-training programs."

Adds Harvey: "And after getting a job, they're able to focus on noncrisis issues, like if they've been estranged from their family while being homeless. They can get child support forgiven, they're able to see kids and repair damage that was done."

The BEACH Project has led to other grants and contracts for ArchCity Defenders, allowing the agency to hire two staff attorneys, including Stephanie Lummus, a 2012 SLU law grad who had been volunteering for the agency while in school. The bolstered staff now allows ArchCity Defenders to handle hundreds of indigent cases at a time.

Yet for all the good work they do, not everyone — especially the powers that be in the small municipalities that border St. Louis — is pleased with ArchCity Defenders.

John McAnnar recalls a time when he attempted to introduce himself to the judge in a north-county municipality but was quickly cut off.

"I know who you are," the magistrate barked back in mock indignation. "You're the ones taking money out of my pocket."

The judge was only half-joking. For many St. Louis municipalities, especially the poorer ones, revenue from municipal violations accounts for large portions of the local government's operating budget.

"Some of our municipalities are seeking to raise revenue through the use of their municipal courts. This is not about public safety," says Harvey. "The courts in those municipalities are profit-seeking entities that systematically enforce municipal ordinance violations in a way that disproportionately impacts the indigent and communities of color."

And residents aren't happy about it. A Facebook page titled "Dissolve City of Pine Lawn Police Department" complains that the department is run "purely on traffic fines" and "has no reason to exist." The site has more than 10,000 "Likes," and perhaps for good reason. Pine Lawn has a population of only 3,275, yet last year it issued 5,333 new warrants, bringing its total outstanding warrants to 23,457.

Adding weight to Harvey's argument: Pine Lawn is 96 percent black, and its per capita income a measly $13,000. In 2013 the city collected more than $1.7 million in fines and court fees. That same year, the affluent west-county suburb of Chesterfield, with a population of 47,000 (about fifteen times bigger than Pine Lawn) and a per capita income of $50,000, collected just $1.2 million from municipal fines, according to statistics compiled by the state.

Several other north-county municipalities with high populations of African Americans also have similarly high warrant-to-population ratios as Pine Lawn. Country Club Hills, with a population of only 1,274, issued 2,000 municipal warrants last year and has more than 33,000 outstanding. Over 90 percent of Country Club Hills' residents are black and they have a per capita income of under $14,000. The same is true in nearby Wellston, a city that's 97 percent black and has a per capita income of less than $12,000. Last year its municipal court issued more warrants than the city has residents — 3,883 new warrants compared with a population of 2,300.

Monica Green, 33, knows the situation well. Between 2007 and 2013, the homeless mother of seven racked up about 40 traffic tickets, many of them in Wellston.

"They came in bunches," says Green. "They'd give me maybe four at a time. You get pulled over twice a year, that's already eight tickets."

Green, who has worked as many as three jobs at a time to make ends meet, had no way to pay the fines she received for violations such as driving without insurance and a busted taillight. When she couldn't pay those off, she started getting tickets for driving with a suspended license, too.

Buses couldn't get her to the baby sitter and work on time, so she kept driving.

"I didn't have a choice," she explains. "I might get pulled over, I might not. And if I did, I just hoped they don't tow my car and lock me up."

The fines and warrants kept coming. Eventually, Green's traffic tickets in Wellston, St. Louis and Breckenridge Hills totaled $1,200.

"I didn't have the money. It just wasn't there," she says.

A case worker at the homeless shelter where Green lives put her in touch with ArchCity Defenders. With a couple of letters to the court, attorney Stephanie Lummus was able to get Green's fines in Wellston reduced from around $900 to $100. Lummus was then able to get Green's $400 in fines to St. Louis reduced to community service. Without legal assistance, Green says, she just would have kept hoping that she didn't get locked up whenever she drove to work.

"Some of these cases do not take that much time for a lawyer to get involved in. Sometimes, it's just a phone call," Harvey says. "It's a very powerful phone call, but it's a phone call most people can't make."

That's especially true in municipal court, where defendants are not offered any legal aid. Couple the lack of assistance with the heavy fines people are forced to pay relative to their income, and it's no wonder so many of ArchCity Defenders' clients are leery of the system.

"Traffic courts are where most people interact with the justice system," says McAnnar. "And if this is how the justice system is treating people, that breeds complete mistrust for the system as a whole."

"And it's mistrust based on reality," adds Harvey. "You don't have to be a genius to see that when the judge asks you, 'Do you plead guilty or guilty with an explanation?' and regardless of the answer, the next instruction is to go see the woman at the cashier window."

But there might be a solution, and it's a simple one.

"What can happen is just change the sequence," McAnnar suggests. "Just allow someone when they show up to tell the municipal judge, 'I'm poor. I make $3,000 a year. I can't do anything about that. That's where I am.' Let them make that argument at the beginning instead of making them plead guilty, assessing a fine, and then trying to unravel everything and go backward."

This, argues McAnnar, would prevent a litany of problems for poor people and save city courts significant amounts of money in court and jail costs. It would also eliminate a few barriers that stand in the way of those people who genuinely want to improve their lives.

"People are entitled to an indigency hearing," adds Harvey. "But many people don't ask for it because they don't know about it."

Earlier this year, Melvin Bain was back at the St. Louis municipal courthouse for his trespassing charge at Lumière Place Casino. Only this time he had Lummus by his side.

Lummus remembers standing next to Bain in the courtroom, where the smell of firewood hung in the air, a result of her client trying to keep warm the night before at his camp along the riverfront.

"We know a lot of the homeless folks at the Landing because we deal with a lot of their friends," says Lummus, who was told of Bain's plight from another man staying along the riverfront. To Lummus, the charges facing Bain were unjust.

"This guy did not deserve a B misdemeanor," she continues, adding that it's almost as if the city has made being homeless a crime. "If you're outside, you're trespassing. If you pee outside, that's public urination. If you beg for money, you get a panhandling charge."

"Yeah, they gave me tickets for panhandling," Bain sighs in disbelief.

Eventually Lummus got Bain's panhandling fines thrown out. Meanwhile, his trespassing citation will be dropped if he stays out of trouble through his next two court appearances.

For most attorneys, Lummus' work would have ended there. But under the holistic- defense model, her next step is trying to get Bain into permanent housing. That way he won't be so susceptible to another trespassing charge or any of the other municipal violations that impact the homeless.

Lummus, who is a Navy veteran like Bain, figured he'd be a good fit for St. Patrick Center's Project HERO (Housing, Employment & Recovery Opportunities), a program that helps homeless vets get back on their feet. Participants get their own apartment and pay one-third of their income toward rent.

The problem was that Bain didn't have the paperwork to prove his military service. Lummus went through the bureaucratic process of getting him verified through the Navy and, finally, admitted to Project HERO.

Bain also found a dishwashing job at a coffee shop. He's working now and paying his way. For the first time in years, it's unlikely he'll go through the day at risk of picking up a trespassing or panhandling citation.

"It feels good, really good," Bain says. "Steph — she's my little guardian angel."