People started to drop during the first weekend in November.

Staggering, nearly passed out on their feet, they crashed to the sidewalks in a drab stretch of St. Louis' downtown. The stricken vomited, and some shook in the grip of seizures. Others slipped into zombie-like states of near catatonia. One man, unable to break his own fall, plunged face-first into the concrete and bashed out his front teeth.

A bad strain of synthetic marijuana, or K2, was just beginning to hit the city. Sold for $1 or $2 per joint, it swept through St. Louis' homeless community, with the primary concentration of overdoses striking sidewalk encampments that bookend the towering shelter at New Life Evangelistic Center in the 1400 block of Locust Street.

Nearly overnight, emergency calls began to flood city dispatch lines.

"You would be at one call, and someone would walk up and tell you there's another person down over there," St. Louis Fire Department Captain Garon Mosby says. "We were getting multiple overdoses — five, seven at a time."

Police Chief Sam Dotson was driving past during one of the early days of the outbreak when he spotted a half-dozen people down "in convulsions and foaming at the mouth" and stopped to help. It wasn't long before the police and fire departments decided to shorten response times by posting up on Locust and waiting for the next OD. They were soon joined by TV trucks and news reporters. By the middle of the week, the canyon-like strip of the old garment district was lit with the strobes of red and blue lights and camera flashes.

And still people were going down. The fire department's Bureau of Emergency Medical Services usually handles about 70 overdoses in a typical month. During the first week of the bad synthetic marijuana epidemic, the bureau ran 158 calls for K2 alone. The surge of emergency summonses finally began to break after five or six days, but the fire department's EMS still logged another 51 calls during the first five days of the second week.

None was fatal, but the frightening spate of overdoses left a lasting impression. This brand of K2 — some were calling it Tunechi, a reference to the rapper Lil Wayne, who has a history of seizures — caused dozens of people to overheat, seize and hallucinate. A majority became combative in their incoherence, wrestling with the very people who'd come to help them, authorities say.

"I know you've seen the TV show The Walking Dead," Mosby says. "Some of them were truly like that."

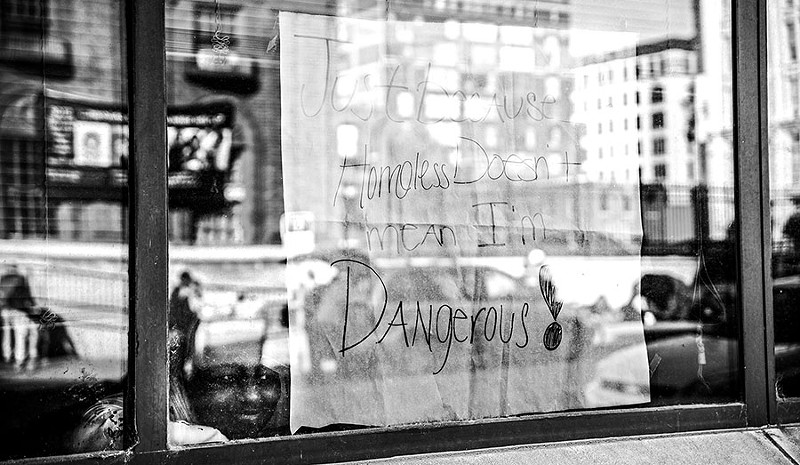

The unsettling episode was set against the backdrop of a renewed controversy surrounding New Life. The shelter's founder, the Rev. Larry Rice, saw the sudden onslaught of overdoses as both a tragedy on the human level and, in a broader context, a consequence of what he suspects is a conspiracy to undercut his life's work. Rice, a tall man with a boyish face even at age 67, has been fighting a years-long battle against the city and his neighbors to keep the shelter open.

Just as the K2 outbreak was beginning to hit, on November 9, the St. Louis building commissioner issued New Life a cease-and-desist order that gives Rice 30 days to close the shelter. Brad Waldrop, a longtime critic of Rice, filed a nuisance lawsuit against New Life a week later, alleging the pastor intentionally attracts people who need serious help to his doorstep and then turns his back as they wreak havoc on the neighborhood.

The suit cites the K2 overdoses as sparking an "unprecedented level of chaos and panic in the community," and lays the blame on the lawless atmosphere surrounding New Life.

In response, Rice points out the encampments are actually in front of the Waldrops' parking lots, largely comprising people who either won't come into New Life or have been barred for breaking the rules. He claims as many as half of the people hanging out on the sidewalk aren't even homeless — they just come to kill time or smoke K2. Waldrop refuses to clear them away because they're politically useful, the pastor says. The greater the chaos — Rice's theory goes — the more New Life's loft-dwelling neighbors will push the city to force the shelter to close.

"They're doing it to make us look bad," Rice says.