Chris Ward has a simple plea for the listeners of St. Louis.

"You know when you get out of the shower and you slip into that computer chair, and you open up an incognito browser, and then ten minutes later — maybe five minutes later — you feel ashamed?" he queries into the air room's microphone. "You're not gonna feel ashamed when you go to support dot KDHX dot org and help our little music station grow and do our thing, and be loud and be stupid and scream and — whatever, man! You can do it. Just be part of this. We're a community station, and we depend on you!"

It is the night of Monday, August 25, and Ward is hosting his weekly radio show, loudQUIETloud, on KDHX (88.1 FM). This week's program is outside of the ordinary: The station is in the midst of what it has termed an "urgent" pledge drive — one which has been moved up suddenly from the fall date on which it was initially planned.

A poster board hangs on the wall; drawn in sharpie is that familiar thermometer infographic often used to indicate progress on a fundraising goal. At the top it says "$200,000." It's colored in to just past the $100,000 mark, with a little note of encouragement in the margin: "Yeah!!! 1/2 way there!"

Ward is dressed in a Hawaiian-style button-up over a Dolly Parton T-shirt, and he opts to stand as he alternates between screaming and softly, delicately encouraging donations. Though the station has officially set his program's individual goal at $500, Ward has vowed to raise $1 million by the night's end, at which point he says he will "electrocute myself on-air."

Sounds dramatic, yes, but these are times of high tension at KDHX. 2015 might well have been the roughest twelve months in the indie radio station's history.

At the start of the year, long-time executive director Beverly Hacker revealed to the board that the non-profit organization had lapsed on its payroll taxes and owed money to the IRS. Though she conceded that finances had always been tight, Hacker pointed to the station's December 2013 move into its shiny new building in Grand Center as a tipping point.

That building had been gifted to the station, which was outgrowing its home in a former bakery on Magnolia Avenue. Rehab work, however, did not come cheap. The cost of the move was just shy of $5 million, and fundraising efforts had generated only half of that amount.

In the wake of the revelation of the organization's tax trouble, nearly half of the board members abruptly resigned. By early August, as bills continued to pile up and staff members saw increasingly wide gaps between their paychecks, Hacker herself was handed her walking papers after 22 years with the station and fifteen in her leadership position.

The dissension continued: Just one month after that, a questionable alliance with Phillips 66 — signed off on by Hacker — angered some members of the local music community.

And so beyond the urgent financial situation is a more complicated — though no less fraught — question. What should KDHX be now that it's growing up? No longer housed in an old bakery, even with its $1.7 million annual budget, it still doesn't feel quite at home in its Midtown office suite.

The next year could well determine the future of the station: whether it remains cussedly independent and wonderfully weird — or takes a step toward being more like everybody else. Whether it can survive one of the worst financial crises of its existence — or whether even bigger changes will be necessary.

The question is whether the strife of 2015 will be a passing bad memory — or a long nightmare that the station just can't shake.

At 13,000 square feet, the building that serves as KDHX's new home is triple the size of its old headquarters, in which the station's staff members and volunteers worked virtually on top of one another. The ground floor houses a modest cafe and an event space, "The Stage at KDHX," which seats up to 140 people at tables in front of a bamboo stage.

Ward is in the air room on the building's second floor, surrounded by state-of-the-art equipment housed beyond a bank-vault-thick soundproof door that alone cost $2,000. Joining him is music director and fellow DJ Nick Acquisto, who is helping to solicit pledges from donors. He is wearing a T-shirt in tribute to the late Bob Reuter, erstwhile DJ of the station's Bob's Scratchy Records program, who died suddenly in August 2013 after a freak accident in an elevator shaft. Acquisto claims the shirt is "for luck" — and that it is working.

A photographer, singer/songwriter and radio personality, Reuter's name is sacred in many St. Louis circles, and he's perhaps more venerated at KDHX than anywhere else. The south-city firebrand was known for his over-the-top, howling approach to radio, throwing records across the room at times and always bringing a borderline-insane energy to his broadcasts that set them apart from commercial radio fare.

"KDHX is weird," Acquisto says into the mic. "We are outside of the norm. We do things differently. We sound strange. We always have, we always will. Some people don't like it, but we don't exist for those people. We exist for you. We exist for the listeners of St. Louis who listen to real radio, right here. We've been at it for nearly 30 years. We exist for the people out there that say, 'Normal is a little bit boring.'"

The ensuing two hours are certainly weird. Ward screams names of donors — along with "thank you"s — over the mix of rock and punk and old-school hip-hop pumping across the airwaves. He calls out the owner of Imo's Pizza for a "challenge gift." ("I want you to give some of that pizza money. You've been poisoning everyone with your pizza for so many years. You should feel guilty putting all that Provel on there! You should donate a little back!") A slide whistle makes an appearance, as does Ward's cat Cricket, who the DJ claims has been trained to ring a tiny bell with each donation (the cat's meows are real but pre-recorded, though Ward makes a big faux to-do about supposedly gathering Cricket out of his crate). At one point, Ward breaks into a boisterous rendition of Celine Dion's "My Heart Will Go On" at the request of a donor.

When Acquisto relays the station's mission statement — "Our mission here is to build community through media" — he acknowledges that "community" can be hard to define. But, he says, "It's sort of like the Supreme Court's definition of 'pornography' — you know what it is when you see it."

KDHX's status as a "community" radio station is one of its most prized assets, earned through years of working closely with the local art and music scene. Its DJs — all unpaid volunteers — frequently play music from St. Louis artists who wouldn't otherwise see airplay, alongside more established national acts. Since the station is a non-profit, its staffers earn less money than they'd pull in at a commercial station. Even Hacker was making less than $100,000 a year, according to KDHX's tax returns.

DJs theoretically have the freedom to play whatever music they wish without anyone exerting control over content. The lack of corporate ties also allows the station to be more nimble. Simply put, no one is telling KDHX how to run itself.

But lately things have gotten more complicated. In 2010, the station launched an ambitious new marketing campaign ("independent music plays here") and a striking new red-dot logo. A marketing director was hired for the first time, with the hope surely that revenue would follow.

Yet the money that came in was never enough for the station's new ambitions.

Tax returns show increasing budget deficits. KDHX went from eking out slight profits in 2011 and 2012 to shortfalls of $99,000 in 2013 to $460,000 in 2014. In 2014, the most recent year in which detailed financial records are available, it wasted $12,676 on bank overdraft fees.

In its financially motivated bid for "stationwide appeal," too, the music has begun to represent a lot less diversity. Hard-edged or abrasive music such as punk rock or metal has largely disappeared from the station's programming in favor of blues or banjo-driven folk – or, at best, has been quarantined within late-night hours.

And in May, all of KDHX's talk radio programs — long-time favorites Earthworms, Literature for the Halibut, Collateral Damage and Collector's Edition — were converted to podcasts as the station moved toward a music-only format. That maneuver raised some controversy of its own, with dozens of programmers signing a petition against it.

See also: KDHX Takes Talk Shows Off the Air; To Be Podcasts Only

But Ward doesn't get into any of that. He only notices that as soon as Acquisto says "pornography" on air, the phones light up. In response, Ward screams the word at the top of his lungs four more times.

He reads comments from those donating money as well.

One comes from Katie in Pocahontas, Illinois. "I'm a young dairy farmer on the other side of the river," she writes. "Without KDHX I would be forced to listen to obnoxious commercials, Maroon 5 and Three Doors Down all day. I am grateful every day I don't have to put myself through that, and stick to KDHX... We sell a colt cow every week — maybe I'll pull some strings and send a livestock check your way. Full-grown colt cows go one grand, easy. I know that. I am from a farm. I know it sounds creepy knowing a dead cow might save you guys, but it's also sort of biblical or something."

Ward replies with a rambling rant about his own (possibly fictional) farm upbringing — involving his mom popping the eyes out of frogs with a pocketknife and saving them in a drawer, and his uncle throwing bags full of cats into the river — before abruptly teeing a befuddled Acquisto up for another plea. ("Wow. That's a tough one to follow" is Acquisto's immediate response.)

"Please, please, for the love of God, save us from corporate radio," reads another from a listener named Lonnie.

"Lonnie, we're trying," Ward responds. "Love you, buddy."

"Thank you, Chris, for honoring Bob Reuter's important work," Tim from St. Louis writes. "Radio is for more than just playing records."

"Bob is here. I can't stress this enough, guys — he is in the walls," Ward says to Tim. "His physical ashes are in these walls. Therefore this building is important to me. So no matter what you think of the situation or what's going on, we owe a debt to Bob."

Reuter's ashes are indeed in the walls. When he died in 2013, KDHX was at work rehabbing its new headquarters. A small group placed some of Reuter's remains into the walls of the air room.

"We gotta keep doing this thing," Ward continues. "I don't care where we do it. I don't care if we are in a bakery; I don't care if we're in a big building with shiny things. This is important, what we're doing. I believe it."

In many ways, Ward and loudQUIETloud are Reuter's natural heirs. Ward's show made its debut on March 10, 2014; Reuter's last show aired in August 2013. Ward's irreverent and manic approach helps to fill the gap Reuter's departure left on the airwaves. Ward is passionate and fearless and a little crazy as well, and he just may represent KDHX at its off-the-wall creative best.

The situation that forced the urgent drive, meanwhile, may represent the station at its bureaucratic worst.

In August 2015, Hacker published a letter on the Riverfront Times website revealing that she'd just been fired from KDHX. It was both a way to break the news and a canny way to take control of the narrative – and it was widely read across St. Louis.

But the letter was more than just an acknowledgment of her own departure. In it, Hacker publicly outlined for the first time the station's financial troubles.

Hacker described the decision to move to Grand Center as a "leap of faith." The problem, she acknowledged, is that the station leapt without all the financing for the move in place — and after the move, major donations stalled. Bills began to pile up.

"Changes had to be made, and I made them — open staff positions were not filled, other staff positions were cut, important equipment purchases were delayed, marketing efforts were cut back, and I made daily decisions on who got paid first," she wrote. "Payroll, artists, critical utilities, equipment leases and local businesses made the first cut. Many others have had to wait, and in some cases, are still waiting."

Perhaps most troubling: After the station fell behind on payroll taxes, Hacker entered into an agreement with the IRS to take on personal responsibility if back taxes were not paid. (The IRS declined comment on any matters affecting any individual organization or entity.) Hacker only informed the board after the fact — leading to a mass exodus of board members.

Hacker is collected and calm when discussing the situation over coffee at Mokabe's on South Grand in October 2015. She is clad in a pink and white hooded sweatshirt with the sleeves rolled up, revealing a tattoo on her right wrist of the Coonley Playhouse window, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Her tough, no-nonsense exterior mostly hides the shock she is still feeling from her sudden termination, but the slightest semblance of bewilderment remains as she elaborates on the station's financial difficulties.

"It was really tight when we moved, but it was not insurmountable," she says. "We had done all of our projections based on a couple things. One was that the ground floor — the restaurant and the event space — was actually going to be operated by someone else. And we had projections of a certain amount of income from that. Well, really quickly we realized that was not going to work, and so we ended up taking on the restaurant and event space ourselves. So that was a really big hit.

"And then we also had projected to both collect and bring in more capital funding, but once we moved, it got very difficult to get capital donations," she continues. "And there were people that did not pay their pledges, so it got more critical toward the end of 2014. We were in a position to where, at the end of [2014], if we had made $300,000, we could have paid off all the payables — all the taxes, everything. That didn't happen. We only got $111,000, and so we went into January knowing we needed to have that $300,000, plus our regular operating expenses that we needed to make it work, to pay off the old payables, to pay the taxes and get even on everything. Didn't happen."

Hacker's critics have said that she hid the depth of the station's financial woes from both the board and the staff — that the board's wake-up call came from learning of the payroll tax problem, while the staff became aware once paychecks started arriving irregularly. The situation culminated in staff members, led by chief engagement officer Kelly Wells, approaching the board with their concerns. Shortly after, board president Paul Dever moved to terminate Hacker, and Wells and chief content officer Ann Alquist were placed into the temporary positions of co-interim executive directors.

Hacker takes issue with that narrative.

"The information about the finances — I will say this on record — is that you should really ask the board. They knew early [in 2014] what the financial situation was, they had accurate, timely financial statements every single month and they agreed to raise $300,000 at the beginning of [2015]. When I left they had raised none of that. Every month in my director's report, from January [2015], I had been telling them the paychecks have been late and that we were in financial difficulty — that I needed their help. So the thing about mismanagement or them not knowing what was going on is completely false."

While plenty of people have pointed the blame at Hacker — "I believe the word is 'scapegoat,'" she says — they are not talking on the record. Neither are KDHX's brass — Dever, Wells and Alquist each declined to comment for this story, despite numerous (and, some might say, doggedly persistent) requests, citing a refusal to discuss "personnel issues."

Even when it was made clear that Hacker herself did not need to be the topic of conversation, all three still refused. At one point a sign was even posted in the station's air room telling DJs not to speak with the media, or anyone else, about its finances or former director.

In November, Alquist announced that she had taken a position at a daily newspaper in Maine, which seemed a particularly bad omen. If the ever-declining state of print media is preferable to the current status of KDHX, then just how bad is the latter?

Alquist, predictably, declined to comment.

Friday, September 11, is a particularly beautiful day in St. Louis, with clear skies and temperatures in the 70s. The street has been blocked off in front of KDHX's building, with a medium-sized stage set up for an event.

It is this season's third and final installment of Grand Center's "Music at the Intersection" series, and Son Volt's Jay Farrar is slated to play along with several additional St. Louis acts at a variety of Grand Center venues throughout the evening — the Riverside Wanderers, the Fog Lights, Brothers Lazaroff, the Dock Ellis Band and the Hobosexuals are among those performing. Vendors including Firecracker Press, the Big Shark Bicycle Company and Urban Chestnut line the street.

But there is one business entity whose presence is significantly louder than all of the rest: Texas-based Phillips 66. The oil company's logo is wallpapered all over the vendor tents, the barricade fences, the stage — any attempt to count all of them would be a truly Sisyphean task.

Mayor Francis Slay is present as well. At 6 p.m. he is slated to dedicate a new 1,200-square-foot mural on the west side of KDHX's building. Framed as a gift to the station, the painting depicts an explorer paddling a canoe toward dozens of St. Louis landmarks and institutions. At its highest point is the number "66," framed inside a heart. It isn't exactly the same as Phillips 66's logo, but it isn't exactly different either.

Following a ten-second moment of silence in "honor and remembrance of the victims of September 11, 2001," Mayor Slay dives right in to Phillips 66's newly launched ad campaign — "66 Reasons to Love St. Louis."

"So. Sixty-six Reasons to Love St. Louis!" he begins. "Well, I think I could come up with a whole lot more, but this is a fun and creative way for business to support our community and create a beautiful public art installation."

The oil company paid $20,000 to the father-daughter artist duo of Robert and Liza Fishbone, who painted the mural. Another $20,000 went to the "Music at the Intersection" series, for which KDHX was a partner, but Hacker insists that every dollar went toward "staging and sound systems and street closings and all the logistical stuff. And a whole lot of advertising — there were billboards all over town. None of that money came to KDHX."

The only compensation the station received, then, came from its work helping to curate the actual "66 Reasons" list of St. Louis landmarks, in addition to rounding up local artists to contribute to a Soundcloud playlist for additional promotion. KDHX was paid $2,500 for that work.

While the campaign generated plenty of good headlines for Phillips 66, for KDHX it was more of a mixed bag. Some in the community viewed its mostly unpaid participation as a missed opportunity for much-needed financial help. Others decried any relationship with the oil giant as contradictory to KDHX's status as an "independent" organization.

See also: New Mural Comes from an Unexpected Partner: Phillips 66Hacker, who approved the deal, views the criticism with some bemusement.

"I think it is really really funny, all the controversy about the mural, because one of the things that KDHX has always been incredibly committed to is getting artists paid," she says. "And the people that got paid for the mural were the artists."

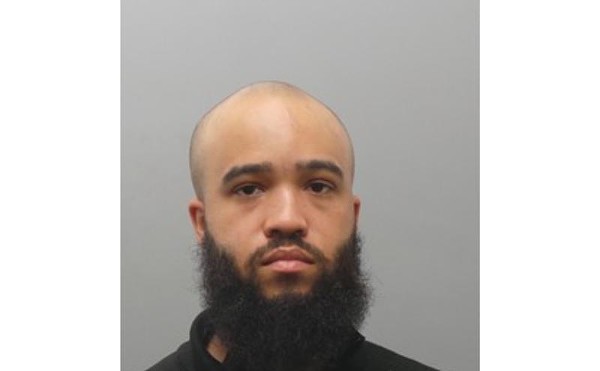

Chris Baricevic takes issue with that.

The head of locally based Big Muddy Records was a friend and bandmate to KDHX's beloved Bob Reuter. His label is home to Bob Reuter's Alley Ghost, Reuter's band at the time of his death.

"I'm definitely for artists getting paid," he says over coffee at the Mud House on Cherokee Street. "However, I think that KDHX needs to be working on building a community that can support local artists without having to invite in outside corporations that have international interests. I mean, if she's talking about the artists that actually painted the mural, then she's talking about very few people. And again, that's cool that they got some money, for sure. But they got some money putting a big red, white and black '66' on the side of an arts program building."

In addition, Baricevic says, two of the bands on Big Muddy's roster had their music used for the "66 Reasons" campaign without receiving compensation of any kind. KDHX enlisted their participation without first divulging that the campaign was related to Phillips 66. The Rum Drum Ramblers and the Loot Rock Gang, both of which feature the work of local guitarist Mat Wilson, entered into an open-ended contract under what Baricevic considers to be deceptive circumstances. (Wilson declined to comment for this story, directing questions instead to Baricevic.)

"Mat received an email [from KDHX] asking him to be involved in the '66 Reasons to Love St. Louis' campaign. The email was kind of vague and left out a lot of details," Baricevic says. "I can corroborate this because I received the same email for Alley Ghost. ... Mat just kind of understood it as, 'This is a KDHX thing — sure, well, we'd be happy to help out.' Mat has been a huge supporter of KDHX. So he agreed and signed the paperwork.

"After the campaign had started he found out that this is actually a Phillips 66 campaign. He went back and checked the correspondence and learned that that information was not presented to him. The information was included on the contract, insofar as the header of the contract said 'Phillips 66' and they were mentioned as an 'interested party.' But if you are an artist that is not versed in contracts, that stuff all looks like Greek."

Wilson wasn't the only local artist to sign on the dotted line based solely on faith in the station's good intentions. Melinda Cooper of the band Town Cars also received a release and signed it.

"We always do things for KDHX, so I thought, 'Oh, this is from someone I trust,'" she explains. It wasn't until later that she realized that the oil company was involved. "It was really upsetting."

But that association wasn't even the most egregious aspect of the agreement, Baricevic says.

"The contract itself was written very poorly and in vague enough terms that by signing it and returning it they actually were giving these companies license to use their entire catalog, for no compensation," he explains.

Baricevic and Wilson were able to secure an attorney through St. Louis-based Volunteer Lawyers and Accountants for the Arts. She sent a cease-and-desist letter and ultimately got the contract dissolved — but not before songs from each of Wilson's bands were used in promo videos for the oil company's ad campaign.

Matt Harnish, guitarist/vocalist of St. Louis' Bunnygrunt, recognized early on that the contract did not work in the favor of artists — it failed to list a specific track or to specify a time frame for use. He declined to sign.

"Then we showed up on the playlist anyway," he says. "I was getting ready to send a complaint when I noticed that we just as quickly got removed. Unfortunately the playlist had already been sent off to the advertising agency and we ended up getting used in one of the clips. Without our permission. Because KDHX sent them our music without our permission. A station that had always been a force promoting St. Louis music, and had always been about the little guy going up against the big guy, gave our music away. For free. To the big guy!"

He adds, "I don't think it was done maliciously, and I won't flatter myself to think that we were singled out at all, but it was a cavalcade of incompetence from the get-go, and our song is still out there tied to some dumbass ad campaign, and will be forever. And it's KDHX's fault. And that sucks."

"The bigger issue is that we as a creative community feel like KDHX has just kind of turned their back on us, the community that has built KDHX to be what it is," Baricevic says. "Not necessarily our generation, but the generations that have come before us, of people like us. And this is supposed to be an organization that is part of our community, that's helping our community, and they've recently kind of taken more of a sleek, profit-driven marketability approach that kind of leaves us in the dust."

The station's November 19 board meeting is a sparsely attended affair. President Paul Dever is present, as is board member Ray Finney. Joan Bray calls in and participates via speakerphone. Gary Pierson arrives about fifteen minutes into the meeting.

The rest of the eleven board members are MIA. Jeff Halzago, a physician, is working at an emergency room. Tom Livingston is flying and unable to call in from the plane; Franc Flotron, too, is traveling. Sam Coffey is in Dubai, as those in attendance are able to surmise from his recent Facebook postings. August Schlafly is "with clients." The whereabouts of James Hill and Mark Hamlin are never made fully clear, but in any case, they are not here.

Kelly Wells, the station's remaining interim executive director, is present. But without a quorum, the board can take no official action. Wells is disappointed. ("But I have all these packets printed," she says with a wry laugh.)

The spare furnishings of the board room belie the notion that unnecessary extravagances may have contributed to the station's financial difficulties. A modest conference room table formed out of four smaller tables sits in the middle. The chairs are all mismatched; the walls unadorned. If money has been spent wastefully, this room doesn't show it.

But the lack of members in attendance is telling, too. The board meeting is taking place on the heels of one of the most "urgent" financial drives in the station's history, yet a majority of board members are nowhere to be seen. (KDHX declined to provide minutes from past meetings prior to our deadline.)

Twelve minutes into the meeting, the group is already entertaining the idea of letting Bray off the phone, since they have no ability to conduct business. The members then discuss contacting lapsed donors, circulating call lists and conducting the station's year-end campaign. Letters will be sent to past donors who've gone silent, and the board members themselves will make calls to encourage them to come back.

About twenty minutes into the meeting, Wells perks up.

"The only other thing I need to chat about a little bit before next month would be a general feel for the art walk that is happening in the alley," she says. "Grand Center, you know, has a grand plan — Grand Center Incorporated." Part of that plan, she continues, involves an art installation on site, including the alley behind KDHX. "They want to beautify it, basically, and they plan to do this with alleys and walkways throughout Grand Center, and this is the first one. They were awarded a $40,000 grant from the Regional Arts Commission. And I asked — very detailed — there is no corporate money behind this at all."

As the members of the board cheer the lack of corporate involvement, no one in the room seems to notice or care that Wells just stated that the money had been awarded to Grand Center Incorporated.

"What I need to be able to say to them is how we might be willing to let the back side of our building that faces the alley be used for this," Wells continues. "Now, we haven't seen the final proposals from the three artists — they aren't due until mid-December. And at that point we'll have a better idea if there is a mural involved at all, but I wanted to go ahead and put it out on the table that that is a possibility."

As if sensing the fear in the room, she adds, "They have promised me no logos of any sort."

By 7:34 p.m., the board asks a reporter to leave so the group can conduct some "closed-door" business. The exact nature of that business remains a mystery; the station has gone into bunker mode. The silence has been deafening from the top down.

Ward is an exception. Though only a volunteer DJ now, he spent three years as KDHX's marketing director, from 2011 to April 2014, before being laid off for budgetary reasons.

On December 29, just before the start of the new year, he agrees to meet at the Kitchen Sink on Washington Avenue. He is careful to clarify that he is not an authority of any kind at the station now. Still, his experience gives him unique insight into KDHX's present predicament.

"I think you're not hearing a lot from the top because everyone is still sort of figuring out the best approach," he says. "At the end of the day everyone wants to see this thing thrive and succeed. I don't think there's some faction of people looking to destroy KDHX or something like that. I don't see what purpose that would serve.

"I mean look at me: I was fired," Ward continues. "And yet, I love KDHX. ... I mean, nobody stays at KDHX, or any non-profit, forever. The money's not great — you do it for the passion. The people there are the most passionate people I know. They've taken pay furloughs, they've worn a thousand hats, they've done things that aren't in the job description just to keep the place going."

And for now, KDHX will keep going. The urgent fall pledge drive raised $250,000, which, according to a year-end update posted to the station's website, was enough to pay down its most immediate expenses. Ward's own on-air efforts brought in $4,000 — eight times the goal set by the station for his program, and a record amount of money for his timeslot.

Still, KDHX says that it ultimately needs approximately $2.5 million to pay off the remaining costs related to the building.

"So luckily, the good side of that is we pulled it off, we made the money, we covered those most urgent needs," Ward says. "The bad side is we have to maintain that urgency without making people feel fatigued about the station."

With that in mind, there looms the big question: Was the move to Grand Center a mistake?

"I don't know if it's so black and white," Ward says. "I think intentions were good, and I think mistakes were made along the way that they couldn't have anticipated. ... We couldn't have stayed in a bakery that was falling down forever. We would have had to move somewhere. And then somebody comes and says, 'We're giving you this building.' I mean, I'd take it. In a heartbeat."

Faced with the same question, Hacker doesn't hesitate.

"No, absolutely not," she says. "The move was absolutely critical. It's critical for the long-term health of the organization, it was critical from the standpoint that the building that we were in was about to need some really major work."

In time, she believes, the station's new cafe has potential to be a real money-maker: "The other thing is that within about a year to eighteen months there's gonna be over 100 apartments directly across the street, there's gonna be a whole bunch of retail, the number of residences is going up substantially. To me it's a bit of a waiting game. We were a little ahead of the curve getting in there... Had we waited, had we not done what we did and gone forward when we did it would have cost about 30 percent more to do the build-out. And the board knew that and they voted to go forward.

"So to me, everything — all of the things that came out of the move — first of all, it was all done with eyes wide open, so coming back and reading things that say, 'Oh [Hacker] was hiding things' or 'We didn't know,' it's just not accurate. Do people dislike me? Sure, I ran a business for fifteen years. It wasn't a popularity contest, but I think it was absolutely the best move we could possibly make.

"[The station] just needs to grow up, and do that in a way that doesn't change what is core to it and essential, and what makes it what it is."

Ward echoes that sentiment.

"KDHX has kind of a proud history of not knowing if something is gonna work and going for it. And holding hands and jumping off the cliff. And that's kind of what excites me about the station," he says.

"The downside is you run into things like we're in now."