When the University of Missouri left the Big 12 for the SEC in 2012, many fans were upset because the school would no longer play games against its biggest rival, the University of Kansas. University of South Carolina head football coach Steve Spurrier tried to promote a game against Mizzou as the "Battle of the Columbias," since each university is based in a city of that name. He said the winner of the game would receive a trophy.

The idea hasn't really caught on. But still for the game Saturday, a significant number of Gamecocks fans flocked to the parking lot and stadium.

Eric Abel, a 30-year-old native of Greer, South Carolina, says his cousin has been named "the biggest fan of South Carolina in 2012."

I ask him who awarded that honor.

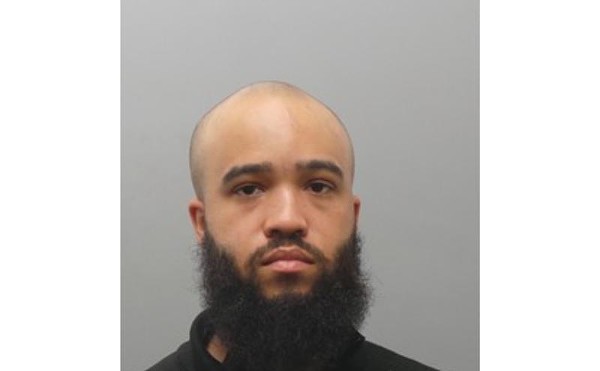

"The Baton Rouge police department," he says, and then gives me a koozie with his cousin's mugshot on it. His group of fans travel to one South Carolina road game each year.

"Usually we have a crew of about twenty, but people didn't really want to come to Missouri," Abel says.

He says he had no idea why. "We got here and were shocked; this place is awesome," he enthuses as his friends play drinking games nearby. "When you look at how great of a college it is and the downtown area, this is one of the best schools in the SEC. Oh, and also there are a couple hot girls walking around."

I wonder whether news of the protests reached South Carolina.

"We were cognizant of it," Abel says. He was surprised when he saw news about how much enrollment had dropped.

He and other South Carolina fans mention the racial tensions in their state, where a Confederate flag flew at the Statehouse until 2015, when Dylann Roof, a Columbia, South Carolina, native, killed nine black people at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston.

"Me and my friends were always proponents of taking the Confederate flag down," says J.W. Brunson, who was in the third generation of his family to attend South Carolina and is now president of the Gamecock Club in Nashville. "We were very thankful that they took it down."

Despite the flag, Brunson says he was "lucky enough" to not have grown up in a racist community. He adds, "I don't want to say that there wasn't racism." The church shooting, he says, had brought the white and black communities closer together.

Just like at Mizzou, USC has dealt with hateful acts on campus. In 2015, the school suspended a student who was photographed writing a racial slur on a white board, which then went viral over social media, according to the Washington Post. Shortly after the protests at Mizzou, about 150 students walked out of class at USC to "protest alleged racial and gender inequalities," the Charlotte Observer reported.

The students, operating under the name USC 2020, made similar demands of administration as Concerned Students 1950, such as "improve and expand minority recruitment efforts in order to increase racial diversity on our campus." They said they had moved up a date for a planned protest because of the events at Mizzou.

"In Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia and South Carolina, blacks represent about a third or more of each state's college-age population but less than fifteen percent of the freshman enrollment at the flagship university," the New York Times reported.

Maybe there were the right elements for a rivalry. At South Carolina, black students made up six percent of the freshman class in 2015; at Missouri, the figure was eight percent.

Or maybe there isn't anything unique about the lack of diversity at the schools.

Shortly after the protests, FiveThirtyEight.com, a data news organization, reported that Mizzou "is almost exactly in line with its peers in terms of how representative its student body is."

Maurice Benson, a former Mizzou defensive back, grew up in Manhattan, Kansas, home of Kansas State University, and has spent much of his life in the two college towns.

"A university brings people from out of the country, and there are black, white, Asian, Hispanic students. You ran across all walks of life," says Benson, 46, who is black. He roomed with black and white players and says he never felt they were treated any differently around town.

He remains an enthusiastic Mizzou fan. A few hours before the game, Benson, who now directs a YMCA center in Topeka, Kansas, is walking around downtown with his daughter and some friends. Like Grady, he believes most racism comes from ignorance.

"Things happen everywhere you go, but to think that this is more of a racist town, a racist place, a racist university, I can't agree with that." He notes that some of his black teammates were elevated to positions including athletic director and associate dean. "To portray this town as not accepting or against anyone who doesn't look like them, I think that's so far from the truth, I can't even speak to it."

But to walk around campus on game day, when the school is at its brightest, is of course to get a skewed perspective. Students who have experienced significant racism may no longer live in Columbia. And black student-athletes' experience may not mirror the rest of the black student body.

"If U were black at my alma mater, and ur name was not Maclin, Denmon, Pressey, English, Weatherspoon, Carroll, etc. You didn't feel welcome," former Mizzou basketball star Kim English tweeted shortly after the protests.

Alex Rideout, a black senior from St. Louis, plays club ultimate Frisbee at Mizzou but came to the school because he wants to be an athletic trainer for a football team.

"It's just the atmosphere of it, where not only the players are a giant family but also the fans, the crowd," says Rideout.

When the protests were occurring — and there were threats against African-Americans over social media, and a truck with a Confederate flag drove by the protesters' encampment — Rideout says he received calls and texts from ultimate teammates to see if he was OK.

Rideout said he had not experienced any racism on campus but understood where the protesters "were coming from."

Once, at a party, he recalls, a white student sitting near him on a couch told him that he was "OK with black people as long as you don't steal my stuff." He says, "Immediately everyone at the party condemned it and shut him down and he ended up leaving."

During the protests, his parents asked him if he wanted to transfer.

"Even though there was a lot of turmoil going on, I have never been one to run from it, and on top of that, my friend group has always been supportive," he says.

But Rideout was already there. What about those who watched the protests as they were deciding where they wanted to attend college?

Students Carlisle Smith, who is black, and Austin Wise, who is white, are walking toward Memorial Stadium just before kickoff. Smith, a freshman from Chicago, says he is "excited to see the fans and the student section." It is the first Mizzou game for each of them.

Smith, a business major, decided to enroll "because I knew some people down here and liked the campus and the culture a lot."

As a black student, he says, "there was definitely some hesitation about what might happen or what could happen but nothing that stopped me."

As to what their first month had been like, both Smith and Wise say they have been having a good time.

Do they feel as though the school has been making a concerted effort to make minority students feel welcome? Says Wise, "I think it's just natural. You see us; we're different races and we're friends."

Their first game begins well. A couple minutes into the second quarter, the Tigers are winning 10-0.