Inside a Costco, anything seems possible. It is a monument within itself, a vastness of pallets and supersized packaging, aisles selling widescreen televisions and caskets and rotisserie chickens. And it is astonishingly lucrative for both the corporation that owns it and any city that hosts it.

That is why, for the promise of a new Costco — and the expected influx of millions of dollars of desperately needed tax revenue — University City is willing to wager a chunk of its soul.

The $190 million project, dubbed "University Place" by Webster Groves-based developer Novus, would install a 158,000-square-foot structure to house the behemoth wholesale club just off the intersection of Interstate 170 and Olive Boulevard, one of the city's most diverse commercial corridors.

Olive is a street of contrasts. It is home to numerous small businesses, and although it is among the densest urban stretches of St. Louis County, it is in disrepair. In many places, the areas between storefront and street are slabs of uneven concrete, the ground bulging and cracked, and cars often use these surfaces for parking, right there on the "sidewalk." Pedestrians must find their own way around.

But for years, what they also find on Olive, to their delight, is a galaxy of immigrant-owned restaurants, making the street the closest thing the St. Louis region has to a Chinatown.

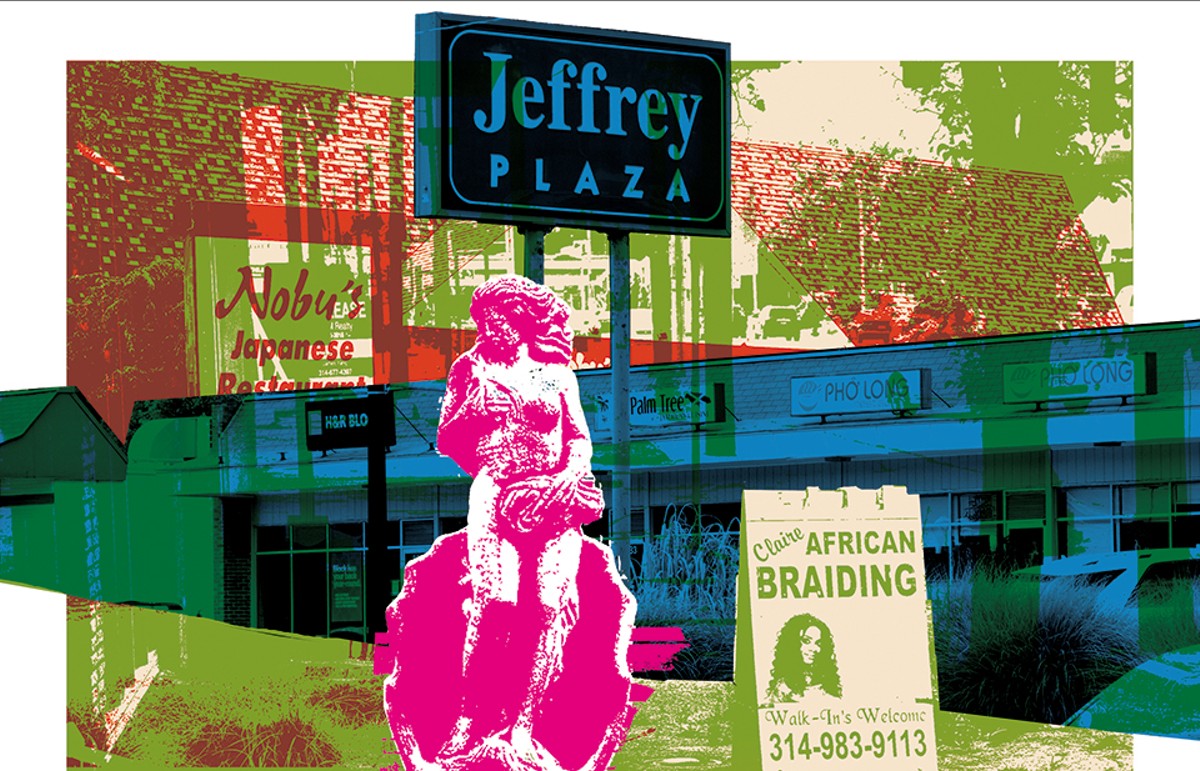

Driving west on Olive toward I-170, one passes an unassuming strip mall called Jeffrey Plaza, home to more than a dozen businesses, a celebrated sushi restaurant, a barbershop and an East Asian grocery. In 2018, the strip mall got a new owner: Novus Development.

In the renderings Novus submitted to the city that year, the entirety of the strip mall is erased within the vast boundaries of a parking lot and the Costco itself. The full project requires razing 67 homes, dozens of apartments, two churches and a school, among other things.

There are all very reasonable reasons to do this, University City officials say. By unleashing millions in new tax revenue, they believe Costco can help revitalize slumping neighborhoods and protect the city from future financial calamities. As part of the deal with Novus, University City committed $15 million in community benefits earmarked for improvements in the Olive corridor and the northern, predominantly black Ward 3. There, neighborhoods remain in a stranglehold of bottomed-out home prices, and the communities are on a downward path of disinvestment and disrepair.

Not everyone is onboard. A spirited opposition movement raised alarm at the scale of displacement, including the loss of longstanding, successful small businesses. Despite vocal efforts, the project is now beyond the reach of its detractors. In June, the city council approved a development agreement with Novus, pledging $70 million in diverted property and sales taxes to help make the project more than just a rendering.

But while "University Place" remains a project that exists only on paper, the people living and working in its footprint are already feeling the squeeze. They can't rent their buildings to tenants when they don't know if they'll be forced out, and they can't sell their homes (or make plans to move to new ones) until Novus' say-so. In more than a dozen interviews with University City residents, business owners, activists and city officials, the picture that arises is one of a city stuck at the starting line, and several use the same word to describe their predicament: limbo.

On the ground, University City's residents and businesses are facing these consequences alone, while Novus insists, with a combination of caution and confidence, that the end is near. Novus tells RFT that it aims to finally start construction in the first quarter of 2020.

But the reality is that not even Novus is willing to guarantee that the Costco project's financing will come together. In the meantime, some in University City are anxiously waiting their payday and relocation. Others are just trying not to fall apart.

For more than 30 years, Letha Baptiste has lived in a 900-square-foot house on Elmore Court, a cul-de-sac of houses built in the 1950s, many smaller than modern-day two-bedroom apartments. Along with Elmore, this corner of Ward 3 has three similar cul-de-sacs, or "courts," named Mayflower, Richard and Orchard — and in Novus' plan, all four are due for "redevelopment."

"They're all just like me," Baptiste says of her neighbors. "We're playing a waiting game."

According to property records, Novus, through its affiliate organization U. City L.L.C., has purchased four of the 54 houses within the "courts," three on Mayflower and one on Richard. However, Novus claims that it has already signed options to buy 90 percent of the residential properties within the project site, and that just nine homeowners remain uncommitted.

On Elmore, however, Baptiste has rebuffed Novus' attempts to get her house.

"I can't speak for anybody else, but I've been here for a long time. I was expecting to stay here 'til my last days of life," she says. "I never ever dreamed of having to move just because they wanted to do a big box store."

Last year, Baptiste says she answered a knock at her front door. On the other side was a representative from Novus, who told Baptiste that the development project would require the site cleared of existing structures (like her house) and readied for construction. Baptiste says she was offered an option contract to buy her home at a later date.

One of her neighbors got the same offer and eventually took it, she says. On Elmore and the other residential courts, home assessments generally land at about $70,000. While Novus never made a direct offer to Baptiste, she says that the prevailing rumor was that the developer was offering homeowners $150,000.

"My neighbor was telling me, 'You need to make up your mind, because if you get whatever they're offering, that's good money,'" Baptiste says. "That's good money to him. But not to me."

Baptiste remembers feeling unconvinced and underwhelmed by Novus' development, as well as the price they reportedly offered. She didn't see a good reason for the redevelopment project to uproot her neighborhood. She told the Novus representative, "I'm not interested."

The Novus representative was, at first, undeterred. "She kept coming back every other week," Baptiste says. "She even went as far as to bringing me a Christmas present, good nuts, so I ate them of course. I still said no to her."

Across the street from Baptiste, Jeff Sharmey and his brother similarly rejected Novus' offer. In an interview by phone, he says he simply doesn't want to move. Despite the buyout offer and promised relocation assistance, he doesn't see his finances stretching far enough to stay in town. "There's nowhere in University City that suits me for what I can afford," he says.

Some might call being priced out of your own city an example of gentrification. Sharmey just calls it "a bunch of junk."

"How does someone make someone move if they don't want to move?" he asks angrily. "I think it's a big waste, a waste for nothing, and it aggravates everything."

And it was aggravation that met the city when, during a series of hearings in the spring and summer of 2018, it first unveiled the plan to the public. During a four-hour public hearing in May, more than 700 people showed up, and more than a few let loose at the presence of Novus president Jonathan Browne. Among other things, they demanded the city and Novus reach a Community Benefits Agreement, add affordable housing to the project and conduct a public vote on the whole matter.

Through the jeering, in a scene caught on video, Browne pleaded with the crowd. "Listen to me, this is good for you," he said. "Do you want me to walk away?"

A few voices shouted, "Yes."

But Browne persisted. "I heard at least one 'no,' that's all I need," he said. "I'm not alone here."

By then, Novus and University City had been in talks for more than a year, working their way through two rounds of proposals to arrive at the final plan to redevelop 50 acres on a prime location near a major interstate. Along with the city's mayor and city council, some residents also saw Novus as a boon.

One homeowner, who lives in one of the courts (and who asked not to be identified by name), says that he decided to sign an option contract with Novus because it was "an opportunity to find something different."

He acknowledges that not everyone in the neighborhood feels the same way. But with his kids grown, he says that he and his wife were already planning to move out of University City. When asked about the price he agreed to, he declines to specify a number, citing a confidentiality agreement he'd signed with Novus.

"I didn't get everything I wanted," he admits. "I told [Novus], if they give everyone $200,000 or more, this would have been solved a long time ago."

Time, though, isn't on the side of even those residents who have signed on to Novus' plan. The unnamed homeowner says he's frustrated with Novus' "deadlines," which seem to disappear without reason. He complains that he's researched potential houses for future purchase, only to see them leave the market while he waits on the developer.

Back on Elmore, a renter of one of the small homes tells the Riverfront Times that she's only recently learned about the Novus project and worries that she may have to move in a matter of months. Judy Forland's landlord has given her no notice or alert. She doesn't know where she'll move, or if she'll qualify for relocation assistance.

"They said they are going to help relocate us, but they haven't given us a date," Forland says. "I don't know the story. I don't know if they could come today or tomorrow."

And so the waiting game stretches on. For University City officials who back the development, it's a game the city can't afford to lose.