At the Missouri State Capitol in January, Keeley Kromat did one of the few things she thought she could do: She begged.

Kromat, a mother of two daughters, told a room full of strangers some of her family’s most personal stories in a plea for them to reconsider a bill that would restrict health care for transgender minors.

Twelve Republicans made up the 17-member General Laws Committee, which Kromat drove two hours from St. Louis to speak to. The chances of them actually considering her words were slim, she thought. Still, House Bill 419, which she came to speak against, was a horror that couldn’t go unchecked.

“The cowardice to target children with your culture war is staggering,” Kromat said to the committee. She spoke in a firm tone as she tried to catch legislators’ eyes. Some sat slouched in their chairs, their faces tilted downward. Others tinkered with phones under their desks. “Gender-affirming care is lifesaving health care. Are you prepared to deny children lifesaving care?”

This was the first time Kromat had traveled to Jefferson City to testify at a hearing. Really, she says, she’d never paid much attention to state politics. Other transgender Missourians and their parents have been thrust into a similar position as they say the state “attacks” their lives.

Missouri is second only to Texas in the number of proposed bills that target LGBTQ+ rights this legislative session, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. GOP legislators in Missouri will try to block access to transgender healthcare before the legislative session ends this week. If they don’t, Governor Mike Parson has said he’ll call legislators into a special session on the matter.

And as Attorney General Andrew Bailey works to restrict access to gender-affirming care through no legislative process, parents and trans folks are left wondering: How much longer can they stay in Missouri?

Kromat’s family is “lucky,” she told legislators during her testimony. They have the resources to leave the state if they have to. But the idea that they would be turned into “refugees” to save her eldest daughter’s life due to a state law was “sickening,” she said.

In the months since Kromat’s testimony, what started as an idea of last resort has become more of a reality to transgender people and their families. They’ll leave Missouri if they have to.

“Finally happy”

When Kromat’s eldest daughter, Rowan McGrew, was in preschool, she had no idea what to be when she got older. Kromat used to lovingly refer to McGrew as “Peter Pan,” the boy who famously refused to grow up.

Several years later, when McGrew was 14, Kromat learned that her child’s hesitation to grow up wasn’t because of some childish determination not to mature. It was because McGrew couldn’t bear the thought of growing up to be the adult man that biology had destined her to be.

But in the three years since, McGrew has “blossomed,” Kromat says. Before, McGrew was sullen and withdrawn; she couldn’t state her own opinions, or would seldom speak at all. She spent hours isolated in her room.

That changed after McGrew came out as nonbinary, then later trans, and started to actualize her gender. She’s now bright and social. She’s a competitive skateboarder. She has a large group of loyal friends. She’s “finally happy,” her mother says.

“Just the level of assuredness in the past two years is night and day,” Kromat tells the RFT. “I don’t recognize who she is compared to then. She’s very much the little kid I had. My bestie again.”

Missouri legislators have gradually started to accept that gender dysphoria is a real health impairment. Even the attorney general’s emergency rule to restrict transgender health care recognizes gender dysphoria as a condition that should be treated (though how and when Bailey, who has no medical background, believes it should be treated contradicts the opinions of most health care organizations).

McGrew describes gender dysphoria as “constant.”

“It’s like a disconnect, like you’re not being perceived how you want to be perceived,” McGrew says.

That’s a feeling McGrew doesn’t want to go back to. Now, she and her mother fear that life-saving health care will be taken away from her.

First, there were the bills. A lot of them. Forty-eight anti-LGBTQ+ bills were filed in Missouri this session. One Senate bill would ban puberty blockers, gender transition surgeries and hormone therapy for new patients younger than 18. Another would require transgender athletes to compete on sports teams that match their biological sex.

Attorney General Andrew Bailey's emergency order would make being trans in Missouri even more complicated.

In all, the order outlines 21 guardrails trans folks and gender health care providers must follow to comply with state law. Here are a few things patients must do:

- Prove, at least once a year, they are not experiencing “social contagion” in regard to their views on gender

- Undergo 15 hourly therapy sessions to explore “developmental influences” on their gender identity

- Minor patients would have to receive a “comprehensive screening” at least once a year for social media addiction and prove they have not suffered social media addiction within six months prior to receiving care.

- Exhibit three consecutive years of documented gender dysphoria

- Receive a screening for autism

- Show any mental health issues have been treated and “resolved.”

Transgender Missourians and their parents who spoke to the RFT view these rules as “impossible” to meet and worry they’ll eradicate access to gender-affirming care.

But for trans people of color in Missouri, gender-affirming care has long been hard to reach.

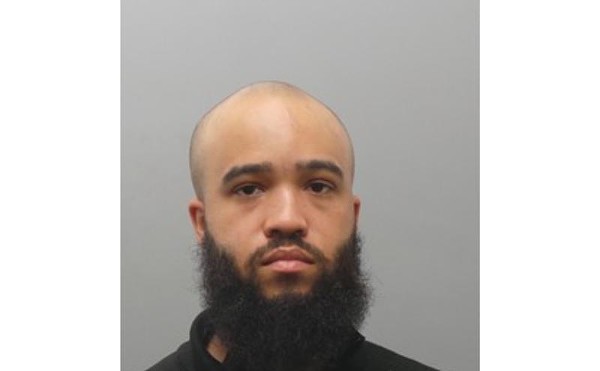

While Bailey’s order would take away her gender-affirming care, Amariah Hardwick says those who face the “double minority” of being Black and a trans woman like her have already struggled to access health care.

“We’ve already been traveling to other states to receive HRT (hormone replacement therapy) or collecting hormones from the black market,” Hardwick says. “This isn’t something that’s new to us.”

“He will never come back”

Christine Hyman’s son, Corey, came out when he was in fifth grade. Hyman didn’t see it coming, but it started by Corey saying he didn’t want to be “in a box.” Not a boy box, not a girl box. So Corey went by they/them pronouns for a while, until he called his mom at a sleepover and said, “I have something to tell you,” Hyman recalls. He came out as transgender and switched his pronouns to he/him. Hyman helped Corey legally change his name about a year later.

It was a “pretty smooth path” until Missouri legislators started proposing measures to restrict trans rights, Hyman says. It started with so-called “bathroom bills” in 2017 after the Trump administration reversed Obama-era protections for transgender students in public schools. The protections allowed students to use restrooms and locker rooms that corresponded with their gender identities.

Missouri bills targeting transgender people have progressively gotten worse since then, Hyman says.

Corey, now 17, was 13 when he first went to Jefferson City to testify. That first year, Corey wrote his testimony out on a piece of paper. Now he looks legislators dead in the eye, his mom says.

“He says what he’s feeling, and it’s not ever nice,” Hyman says. “The only thing he knows is he cannot curse at them.”

It’s the same thing over and over, Hyman says of her own testimonies. She can only tell the same story so many times, so she tries to come up with something different to humanize herself and her family.

“Year after year I go up there and try to plead with them,” Hyman says. “It doesn’t matter. You just get this feeling that they do not care.”

Hyman’s family moved to Missouri from New York about 18 years ago. Soon Corey will be 18, and he’s planning to move away for technical school, according to Hyman.

“He will never come back,” Hyman says. “[Missouri] holds nothing but bad memories.”

Around the end of February, Corey got sick. By then, news of Missouri’s extreme anti-trans legislation was making national headlines as the majority of legislators approved trans sports and health care measures vote after vote. And earlier that month, Jamie Reed, a former case manager responsible for patient intake at the Washington University Transgender Center, had published an op-ed in the Free Press about the center’s “medically appalling” practices.

Among many claims, Reed alleged the center lacked any formal protocol for treatment, that patients were often “disturbed young people” who were not informed of what they were getting into and rushed into treatment. The center lacked regard for parental rights, Reed claimed.

Hyman and her son had been in Jefferson City four Tuesdays in a row fighting legislation around this time. When Corey started to get sick, Hyman brought him to an emergency room. She thought he was dehydrated.

Doctors ended up putting Corey on feeding tubes. Corey had quit eating for 10 days because he was so worried, according to Hyman. It had “finally gotten to him,” she says. “If it wasn’t going to be the legislation, it was going to be this thing that came out from Jamie."

“He ended up in the hospital for 12 days because there was no light at the end of the tunnel,” Hyman says. “He was like, ‘What’s the point?’”

Several patients of the Transgender Center or their parents have since come forward to contradict Reed’s story.

Reed seemed so supportive at the gender center, Hyman says. She was decorated in tattoos, had her hair shaved on one side, and wore glow-in-the-dark yoga pants. “The kids loved her,” Hyman says. “She had this really upbeat personality.”

Reed was the intake specialist for Kromat’s daughter, McGrew. Reed’s account couldn’t have been more different than McGrew’s experience.

“They definitely weren’t pushing it,” McGrew says. “Every step of the way, they told me to carefully think about what I was doing. They asked me the same uncomfortable questions about fertility and if I wanted biological kids all the time.”

Reed’s allegations in the Free Press and in an affidavit to the attorney general (both released on the same day), were enough to kickstart investigations into the gender center by three different Missouri agencies.

The attorney general announced his emergency regulation targeting gender-affirming care on April 13. Since then, the start date for Bailey’s regulations have been pushed back twice. A lawsuit filed by Lambda Legal and the American Civil Liberties Union has caused a judge to push back the start of the restrictions until July 24 at the earliest.

Transgender Missourians and their families hope the lawsuit will annihilate Bailey’s rules altogether. But they’re trying to plan for the worst.

Jennifer Harris Dault, a mother of two daughters, says it’d be “impossible” to follow all the regulations set forth in Bailey’s order. Her eldest daughter, an eight-year-old who is trans, won’t need any medical interventions for a few years. Yet, in the meantime, Harris Dault and her family are considering leaving the state after Missouri’s onslaught on trans rights.

“I think everyone is thinking through, ‘At what point do we leave?’” Harris Dault says. “We’ve certainly been among those. We’ve worked out where we would go, what we would do if we needed to escape to allow our daughter to get medical care.”

“They’re just kids”

It’s always a challenge to communicate to her daughter what the state is doing, Harris Dault says. She tries to make it “less scary” by showing her daughter pictures of people who showed up to hearings and press conferences in support of trans kids. But her daughter still wants to speak to legislators at hearings. Harris Dault asked the RFT to leave out her daughter’s name out of concern for her safety.

Her daughter is a sensitive soul, Harris Dault explains, but a fierce advocate for justice. “She’ll say, ‘I want to hear those bad things, because I want to know what they’re saying so I can get them to believe the opposite.’”

“The parents of trans kids — we just want our kids to grow and thrive and live their lives,” Harris Dault says. “I’m not trying to make her into something she’s not; I just want to support her the best I can.”

Her daughter is so wonderfully herself, but is still no different from any other kid, Harris Dault adds. She loves to read; so much so that she has to be reminded to put her books down to get ready for school in the morning. She loves Pokémon, making funny noises, irritating her younger sister, and school. At her birthday party this year, her friends came over to do science experiments.

“These kids are kids, leave them alone,” Hyman says. “They should be outside with their friends until the streetlights turn on and not worrying about what their state is doing to them. And neither should their parents.”

When asked if there’s anything that gives them hope, McGrew and her mother mention the lawsuit targeting Bailey’s emergency order. They’re hoping it will stop this. But both acknowledged that even if the suit does succeed, there’s still the bills, each a threat of their own.

Kromat and McGrew fall quiet for a brief moment as the totality of all that’s before them sinks in. Kromat later turns to her daughter and smiles. She strokes her hair.

“She’s my hope,” Kromat says. “My little anarchist.”

Coming soon: Riverfront Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting St. Louis stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter