Former state Representative Don Phillips understands the powerful hold of the unknown.

The retired state trooper from the southern Missouri lake town of Kimberling City was adopted as a baby, and like tens of thousands of other adoptees, grew up not knowing where he came from. So when a 75-year-old adopted woman asked him during his third term in the statehouse for help unsealing her birth records, he recognized a familiar ache.

"I knew exactly," he says. "I could empathize with what she was feeling and knew exactly what she was feeling."

Versions of a bill to open original birth records for adoptees had been kicking around Jefferson City for at least fifteen or sixteen years. A hard push in 2000 ultimately failed, and Phillips had no luck when he first tried in 2015.

"'Adoption' seems to be a poison word, even in today's society," Phillips says. "It's like an affliction. That's a hurdle we have to get over. We have to convince people adoption is a good thing."

As he worked on the legislation, he met Heather Dodd of the Missouri Adoptee Rights Movement, a volunteer organization. Dodd's mother had been orphaned at age six, and she and her siblings were sent to separate foster homes. When Dodd's mom tried at age eighteen to track down her long lost family, a social worker told her it was none of her business, Dodd says.

"I grew up hearing that story, knowing that we had other family out there," she says.

Dodd was eventually able to help her mother find her siblings, but she had to get creative to do it. She started by locating her grandmother's grave and leaving a note next to the headstone. The note was later discovered by relatives, who provided the first bits of information. "It took thirteen years to find every last one that was adopted out," Dodd says.

Interested in genealogy, Dodd later helped a woman in an online group track down down her dying mother, who was then in her 90s. The two experiences led her to team up with other volunteers and ultimately launch the Missouri Adoptee Rights Movement group on Facebook.

After the 2015 bill failed, the team — Phillips calls them the "Adoption Army" — came up with a new strategy. So far, discussion had focused on the harm. Opponents argued that any change to the law would essentially break the promise of secrecy made to generations of parents. That reasoning tracked with old attitudes of shame, recalling an era when pregnant teens were spirited away to "visit relatives." Unsealing records now, providing a path for adoptees to contact their birth parents, was seen as forcing women to confront dark secrets.

But Dodd and the Adoption Army were in contact with not only adoptees, but parents who had spent decades wondering what had happened to their children. "We had many, many birth mothers on our side who were really wanting their children to be able to come and find them," Dodd says.

In meetings with lawmakers the Adoption Army focused on the positives of offering a path for people to uncover their lineage. "You're really going to change people's lives," Dodd told legislators.

More than twenty states provide some way for adoptees to request their birth records. A few states, including Kansas, had never sealed them. Dodd argued that the rise of DNA testing and sites like Ancestry.com were already serving as a workaround in the remaining states, including Missouri. Providing adoptees access to their records would allow them to contact birth parents directly, rather than working backward through a DNA match to a second or third cousin, a process likely to involve multiple family members, some of whom might be learning of the adoption for the first time.

"'What sounds more private to you?' That was my question to them," Dodd says. "That's when the light bulb came on for a few of them, I think."

The Missouri Adoptee Rights Act passed easily in 2016, and it proved even more popular than Phillips ever expected.

"We knew there would probably be hundreds [of requests], but it ended up being more like thousands," he says.

The new law included a provision to allow parents who did not want to be contacted to opt out. But few did. The state was overwhelmed with applications from adoptees. Early estimates of six to eight weeks to get records ballooned into six to eight months. The Department of Health and Senior Services fielded 4,044 requests for original birth certificates between October 1, 2017, and December 31, 2018, according to the state. Slowly, the department has worked through almost the entire backlog and is now working on 2019 requests, a spokeswoman says.

Phillips, who left his legislator's job when Governor Mike Parson appointed him to the state probation and parole board, says legislators slog through bills year after year, hoping to pass something that makes a real difference. For him, the adoptees rights act was that bill.

"This was absolutely your dream come true for a bill," he says.

Most of the stories he hears are positive. But even in rare cases when parents do not wish to be contacted, adoptees at least have closure.

"The known is something people can deal with," he says.

He was 47 years old when he tracked down his birth parents. As a longtime lawman, he had the skills and resources others did not. "I was in the business of finding people," he says. And yet there was nothing that could prepare him for the first time he picked up the phone and dialed the number for his biological father.

"It sounded like me on the other end," Phillips says. "I couldn't even tell the difference. It brought chills."

Jason Reckamp's certificate of live birth arrived in the mail in October 2018.

He and his girlfriend, Jennifer Patterson, stared at the name: Karen Piper. When she gave birth to Jason, she'd been sixteen and lived in Florissant. After a lifetime of mystery — not to mention a significant amount of wasted effort and money — Jason finally had the name of his birth mother.

But while it was more information than he had ever had, it was also 44 years old. Surely, she had moved, and there was a decent chance she had married and changed her last name. His biological father was not listed.

Jason and Patterson spent the night googling names and diving down rabbit holes. They would come across a possible match, pull up pictures and search for any resemblance. "It's funny how you can kind of see yourself in every person," Patterson says.

They decided Patterson would write a letter to the address listed on the birth certificate and address it to "the Piper Family," hoping it might seem a little less intrusive coming from a third party.

In the meantime, they kept searching online. Patterson, an attorney, enlisted colleagues to help. One came up with a likely person from a Classmates.com yearbook page for McCluer North High School in Florissant. Jason's sister-in-law was then able to find a crucial piece of the puzzle by locating on Facebook a Karen Piper Harty, whose profile matched the information they had available. As far as they could tell, this was her.

Jason was not sure what do with this new information, gathered in a flurry over three days.

"I went from not having anything for years to having something concrete," Jason says. "Initially, in some ways, that was worse."

It was overwhelming. What if Harty did not want anything to do with him? What if she was horrible? What if they did not even have the right person, and he had to start over? Patterson again offered to make the first contact and sent a Facebook message. It was not only that they thought it might seem less threatening for her to reach out; he had followed so many false starts, he was not sure if he could bear another.

"Every other door I had tried to knock on or open was slammed in my face, or it was just a wall," he says. "I didn't think I could hear, 'No.'"

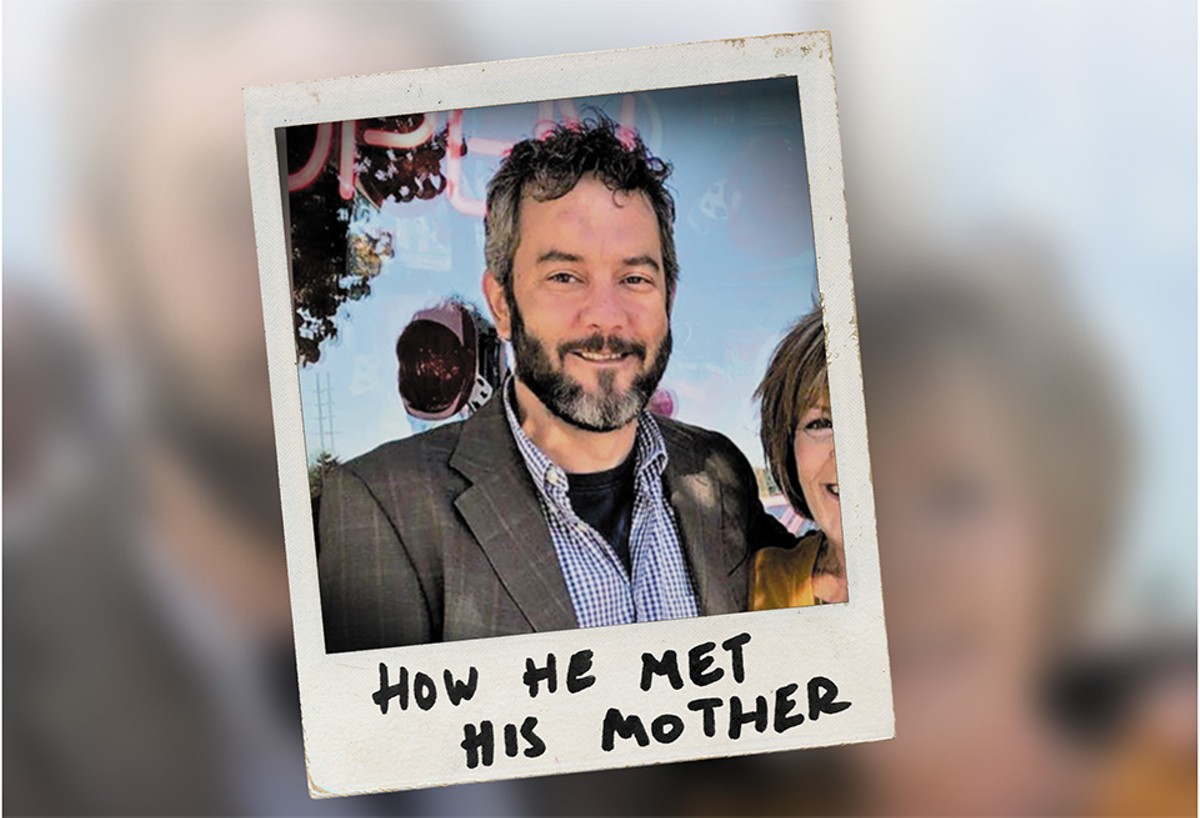

Harty responded to Patterson's message the next day and said she would love to talk. Patterson and Harty spoke first, and then one day in October 2018, less than a week after he first learned her name, Jason picked up the phone and heard his birth mother's voice for the first time.

Patterson watched his face change as he talked. In their relationship, Patterson is the outgoing one. Jason has "always been kind of a loner," she says. But his expression that day was so pure, she pulled out her phone and took a picture. In the snapshot, his eyes are bright and his mouth open in a grin.

"I had not seen him smile like that," Patterson says.

Harty was heading out of town with her husband to celebrate their 30th wedding anniversary. But after several days away, they cut their trip short and hurried home to Missouri to meet Jason.

Harty lives little more than an hour northwest of St. Louis in the small town of Eolia and works at a rural health clinic in Bowling Green. She had previously worked in Creve Coeur and used to have an apartment in St. Peters. All this time, she and Jason had been within an hour or two of one another.

It was equally surreal for her to learn his name: Harty had called him "Jason" after he was born. She thought the Reckamps must have known and decided to keep the name, but they did not. They picked "Jason" on their own.

She reserved a private dining room at BC's Kitchen in Lake St. Louis for their first in-person meeting. She and her husband met Jason and Patterson for lunch. They arrived around 11 a.m., and Jason gave her a bouquet of flowers.

They stayed all afternoon and into the evening. Lunch turned into dinner and then drinks — and the party grew. Harty's younger son, 41-year-old Ryan Hoffman, sent his mother texts until finally they invited him to join them. "He would not stop hugging Jason the whole time," Patterson says. The group did not leave until after 9 p.m.

Jason had tried not to expect too much, but the reality has been better than he could have imagined. Harty was warm and kind. Talking to her felt natural.

"I honestly couldn't have asked for a better situation — a better person, for one, just inside and out, a great person," he says. "It's been pretty cool. It's easy to say now, but if it had been the other way, or the other end of the spectrum, I would have at least had closure."

Harty was similarly moved. She was so nervous heading into their first meeting that she did not sleep the night before. But Jason thanked her for the decision she made all those years ago. He'd had a good childhood and was raised by people who loved him. "All those things you wonder," she says. "You bring them into the world — you want to make sure he's well."

After they parted ways, she contacted someone else she had not seen in more than 40 years — Jason's biological father, Jim Lownsdale.

"I just want to tell you, I had the best experience," she told him.