May 12 was more than just the date of Joe Vaccaro's attempted media tour of the Workhouse. That day, the mayor had her own plans.

At the same time that Vaccaro was leading a group of reporters toward the jail's front doors, Jones' office was making headlines with a lengthy statement that had nothing to do with the alderman's demands for transparency and everything to do with the conclusions Jones had drawn from her visit on April 24. Particularly, the press release mentioned the "first-hand accounts from detainees ... of lackluster COVID protocols, inedible food, lack of running water, rodents and cockroaches, as well as a fear of violent retaliation from Corrections staff."

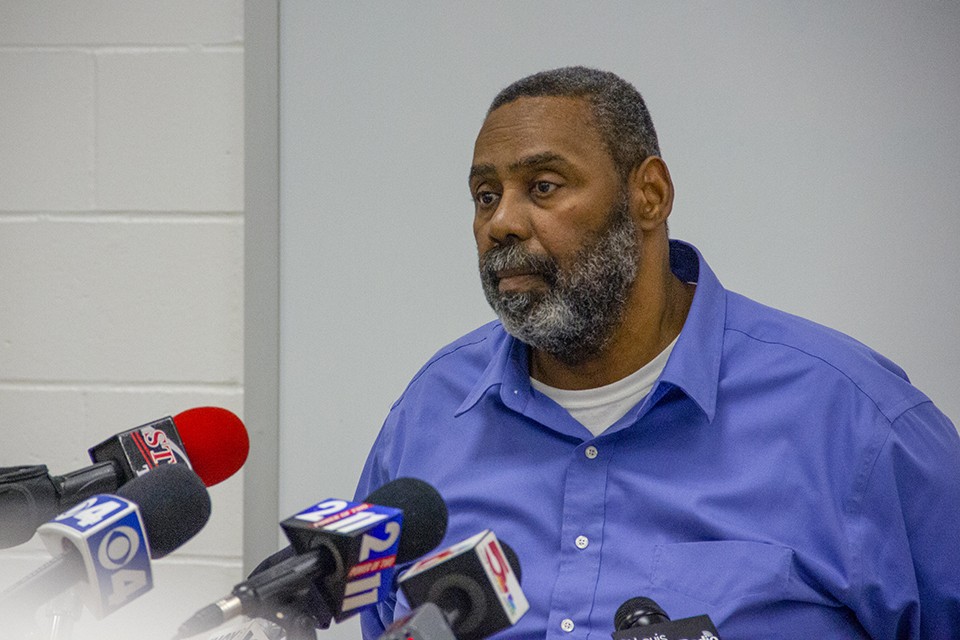

The subject of the press release was the resignation of Dale Glass, whose oversight of the jails, according to Jones, was a "failed leadership" that "left the City with a huge mess to clean up."

It was the end of a nearly decade-long tenure for Glass. He had presided over the 2017 Workhouse heat crisis, the first protests demanding the closure of the jail and, in 2018, the media tours in which he dismissed detainee concerns as mere attempts to "entertain" for the cameras.

That era was over. Glass, the mayor's press release concluded, "was not asked to resign."

Vaccaro was outraged. In a recent interview with the RFT, the alderman argues that Glass was responsible for "tremendous" improvements to the Workhouse; he says the department has evidence that the mayor's jail plans will end badly for everyone — especially the detainees crowded into the newly consolidated Justice Center or relocated miles away from St. Louis.

"We haven't fixed the problems," he says. "And shutting the Workhouse down will do nothing."

The Justice Center, he notes, has already endured multiple uprisings. In February, more than 100 detainees took over a fourth-floor unit, with some using furniture to smash street-facing windows and light small fires that scorched the exterior.

If the Workhouse truly closes later this summer, he predicts, "There is going to be such an uprising from the people who are being moved over to CJC and out of town. They're probably going to break the rest of the windows out."

In Vaccaro's view, Jones is trying to close an invented version of the Workhouse — a decrepit, crumbling and irredeemable jail that he says doesn't actually exist. Based on his own tours inside its walls, he insists the Workhouse is much improved and, in fact, necessary for the well-being of the city's detainees.

It's a notable reversal of roles. For most of the last four years, activists, attorneys and detainees have argued that the glowing reports of a well-functioning Workhouse were blatantly alienated from reality, representing a version carefully constructed by its defenders. Now, with the mayor on the side of the detainees, it's Vaccaro accusing Jones of being disconnected from reality, spinning what he calls "a certain narrative that's not necessarily true."

The swirling accusations also complicate the May 12 visit. Both Vaccaro and Jones dispute the other's account of the tour's origin: Vaccaro claims he notified Jones of his intentions beforehand, only for her office to retract permission in a phone call the night before. Jones tells the RFT she and her staff had "no knowledge of prior approval of his tour" and only learned of his attempt when it appeared on the Board of Aldermen calendar.

"I did talk to her about transparency," Vaccaro maintains, as he describes a phone call Jones says never happened. "I told her, 'I'm going to do this. I'm going to take media.'"

Both sides claim to recognize the real conditions of the Workhouse. But across news reports, media tours and lawsuits, the discourse has often become detached from its subject. In this arena, the experiences of detainees, jail staff and public officials are pitted against one another in a scrum of anecdotes, while the rare media tours attempt to extrapolate short visits into definitive descriptions of what it's like to live there for weeks, months and years.

Two pairs of eyes can look at the Workhouse and see completely different things. One day after Vaccaro's tour, he uploaded several photos from what he described as an "unannounced" tour he took to the Workhouse in 2020, before the pandemic hit.

This was the real Workhouse, he claimed. The one the mayor didn't want the media to see.

Two of Vaccaro's photos show the Workhouse kitchen. Aside from some patches on the floor, the space appears neatly organized and fairly clean. One photo shows a large bread-making table and, in the background, freshly baked loaves stacked on a metal rack. Another shows a large bread oven gleaming in fluorescent light. There are no detainees in Vaccaro's pictures.

It is the same kitchen where, in early May, Heather Taylor filmed insects crawling on the spotted floor, just a few feet from the bread-making table and oven. In fact, the oven is among the only functioning appliances in the kitchen — with its gas ranges deemed unsafe and removed by 2018, today all food must be shipped from the Justice Center. Except for bread.

It's like Vaccaro says: When it comes to the Workhouse, it's all about transparency. But the real question isn't who is being transparent — it's who you believe. And who you don't.

"I just keep going back to, you know, what are they hiding?" Vaccaro says. "There is, obviously, two different stories going on here."