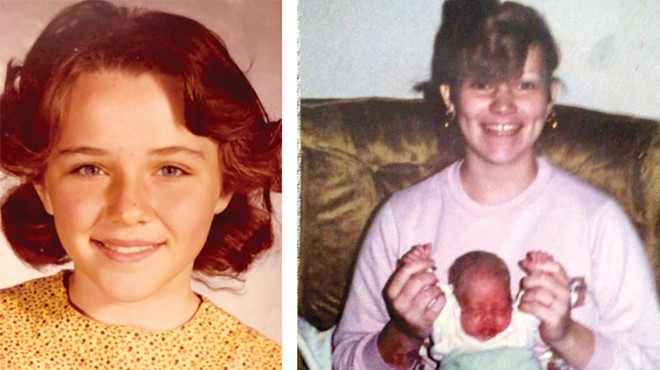

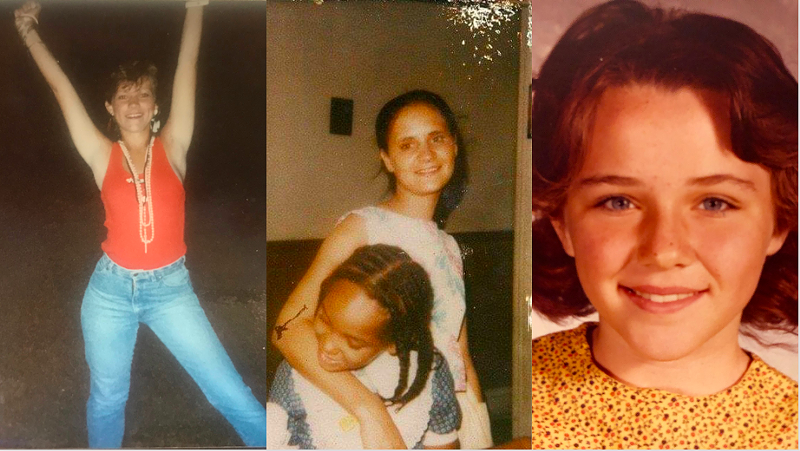

Courtesy Korky Sanders, Antinelle Pruitt, Barb Studt

Three of Muehlberg's victims: Robyn Mihan, Brenda Pruitt, Sandy Little. All three had young children when they were killed

Alvin Maze and Andre Jones, Maryland Heights municipal employees, had just finished clearing trash from a park abutting an apartment complex near Page Avenue around 9 a.m. on the first Thursday of October 1990. It was a perfect fall morning, the bright sun taking the teeth out of the chill in the autumn air. They headed down Basston Drive, an isolated outer road, boxed in by Page on one side and thickets of trees on the other.

There they noticed a brown plastic trash bin sitting in the grassy median between the street and a wooded area.

Whoever had left the bin there had pulled a black trash bag taut over its top and secured it with wire. A stench of rot and decay emanated from within.

“What the hell is in this thing?” Maze thought as he approached it. He undid the wire, removing the bag. His brain struggled to process what he was looking at.

“That’s a human,” his coworker, Jones, exclaimed.

She had dark hair and wore a halter top. A ligature had been wrapped around her neck, a cloth tied around her mouth and eyes. Her legs were pulled tight against her chest, an unnatural position, as if she folded like cardboard.

To this day, Maze vividly remembers her black cross necklace with a jewel in its center.

Maze and Jones had just stumbled across the so-called Package Killer’s latest victim.

Thirty-two years ago, a serial killer with a macabre modus operandi stalked St. Louis, abducting women from the city’s south side and then taunting law enforcement by leaving their lifeless bodies in plain view of morning traffic on the outskirts of the metro. Over the course of 1990, the Package Killer murdered Robyn Mihan, Brenda Pruitt and Sandy Little — all young mothers.

Then the murders stopped. The case went cold. The three women were all but forgotten in the city’s collective memory even as their deaths shaped the lives of those they left behind for decades to come. Cold-case detectives never stopped poring over evidence and case files, hoping for a break.

Earlier this summer, that break arrived, and on Monday prosecutors formally charged 73-year-old Gary Muehlberg for the murders of Mihan, Pruitt and Little as well as another woman, Donna Reitmeyer. The probable cause statement accompanying the charges says that Muehlberg has confessed to killing five women in total.

Mihan, Pruitt and Little were abducted from the Southside Stroll, then the city’s red-light district running along Cherokee Street between Jefferson and Gravois avenues. Muehlberg has confessed to taking them to his house in Bel-Ridge, where the victims were subjected to numerous acts of torture before Muehlberg strangled them. He then left their lifeless bodies in conspicuous “packages”— between a pair of mattresses, in a large trash bin, in a plywood box — along major highways where they would be easily found.

“He’s playing games with us. Leaving bodies out in the open, and he’s doing a good job,” one frustrated detective told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at the time.

A 1991 report created for the FBI’s Violent Criminal Apprehension Program referred to the crimes as the packer killings. In time, the unknown serial killer became known as the Package Killer.

For more than three decades, the Package Killer remained the city’s most notorious serial murderer to elude justice. Until now.

The Package Killer murders began on March 22, 1990, when police say Muehlberg abducted Robyn Mihan from the stroll.

Mihan, already a mother of two at 18, had established a call-girl phone line with her friend Faye Sparks as a way to make money via sex work while avoiding the worst perils of walking the street. However, on that night, the escort service’s phone sat silent in its cradle. Mihan, in the grips of severe crack cocaine addiction, was desperate for money.

“I told her to take a Valium and come down, crash,” says her brother Tommy, who worked security for his sister and Sparks as he battled his own addiction. “Instead, she went to the stroll. She took Faye with her.”

Mihan and Sparks parked on Texas Avenue near Cherokee Street. As a rule, when one of the women got in a man’s car, she would ask him to circle the block once so the other woman could get a look at the car and its driver. This provided a measure of security. But it didn’t always work. That night, Mihan went around the corner onto Cherokee Street looking for a customer, and Sparks sat in the car, waiting for a drive-by that never happened.

Gary Muehlberg had abducted his first victim.

Now 66, Larry Kennedy knew Gary Muehlberg in the early 1990s when the two hung out at the same diner in Overland. Kennedy remembers Muehlberg as a condescending narcissist, twice divorced and openly feared by his then-girlfriend, a diner waitress.

“He was always staring down at somebody,” Kennedy says of Muehlberg, who stands at 6 feet 3 inches. “Gary didn’t like anybody who didn’t respect the way Gary lived.”

Muehlberg worked construction both in St. Louis and around the country. Various people who knew him tell the RFT he was a creepy man with a hostile demeanor who often espoused bizarre ideas. When he was in town, he lived in a rundown house on an out-of-the-way street in Bel-Ridge. According to a 1993 police report, his home was defined by its filth, disarray and a basement where he maintained a “secret room.”

Given what we know now, that basement became what was almost certainly a torture chamber for Robyn Mihan, a place where Muehlberg murdered her.

Joe Burgoon, a St. Louis city detective in the early 1990s who now works cold cases, says that Mihan’s body was found with quite a bit of blood and a ligature around her neck. There was a stab wound to the head that pierced the scalp but didn’t go through and contusions on her face, cheek, wrist and feet. Some of these were defensive wounds, implying a struggle. Others were postmortem. “My guess was she was in pain,” Burgoon told the RFT in 2019.

Korky Sanders, a former boyfriend of Mihan’s, was shown photos of her corpse taken by the medical examiner. The photos show unthinkable torture that still haunts Sanders 30 years later. “Whoever did that to Robyn deserves to be sent to hell the same way he sent Robyn to heaven,” Sanders says.

Four days after abducting Mihan, Muehlberg dumped her lifeless body along State Highway E, 60 miles northwest of St. Louis in Lincoln County. He’d tied two mattresses around her remains, leaving a gory scene soon found by a lone commuter.

Maze and Jones made a similarly gruesome discovery seven months later on October 5, 1990.

It would take months of painstaking work to identify the decomposed remains, but a dedicated fingerprint analyst named Janet Majors eventually found they belonged to 27-year-old Brenda Pruitt, whose family had reported her missing on May 5, 1990, five months to the day before her body was found. She lived near the intersection of South Grand Boulevard and Cherokee Street.

Pruitt’s granddaughter Antinelle Jackson says neither she nor her sister, also named Brenda, know very much about their grandmother. “Nobody ever talks about her because it’s too painful,” Jackson says.

Jackson did recall one ominous story she’d heard from her mom about one of the last times Pruitt was seen alive.

Pruitt took Jackson’s mom, Danielle, out for ice cream on Cherokee Street. While the nine-year-old ate, Pruitt got in an argument with a man in an alley. Pruitt came back to her daughter in tears.

Shortly after that, Danielle didn’t see her mom for weeks, and the family filed the missing-person report.

The ice cream story has become family lore, and Brenda Pruitt’s granddaughters can’t help but wonder if the man their grandmother got into an argument with was Muehlberg.

“My mother, Danielle, died three years ago,” the younger Brenda Pruitt says. “She was depressed her whole life. She was very scared, with anxiety through the roof. This man has caused us more agony than I could ever explain.”

Muehlberg worked for Cherick Construction, a company headquartered in Maryland Heights. Authorities long suspected that the Package Killer may have been employed in construction. The killer used Conex cable, a material used by electricians to wire houses, to tie the mattresses around Mihan’s body and to tie the trash bag over the bin containing Pruitt.

Detectives interviewed employees of Beiner Hardware, where the trash bin Pruitt was found in had been purchased. They identified a semi-regular who may have bought the bins. Police showed the employees photos of three suspects. The employees didn’t recognize any of them, and none of the suspects was Muehlberg.

By the time Pruitt’s body was discovered in Maryland Heights in October, Muehlberg had already abducted his next victim, Sandy Little, whom Muehlberg held captive in his Bel-Ridge house. Police believe Little shared the basement with Pruitt’s dead body.

“He had two people,” Burgoon, the former detective, told the RFT in 2019. “Whoever it was had a couple of bodies at the same time.” Little, 21, disappeared Labor Day weekend 1990 from the Southside Stroll and was found dead five months later, on February 17, 1991, in O’Fallon, Missouri, 30 miles west of St. Louis. A motorist on his way to work that morning discovered her body alongside Interstate 70, crammed in a home-fashioned box.

“He was smart about where he dumped the bodies,” Burgoon said in 2019. “He knew to spread them out across jurisdictions to make things harder for us.”

In addition to the Conex cable, other physical evidence connected the murders of Pruitt, Mihan and Little. The three women had hair from the same type of dog on the clothes they were found in, meaning they were likely held in close proximity to the same animal. According to a 1993 police report, Muelhberg did indeed have a dog in the early 1990s.

All women were found with ligatures around their necks, their faces covered.

Like Mihan and Pruitt, Little was also a new mother when Muehlberg allegedly killed her. She’d given birth to her son Chris Day Jr. in 1989.

In the months prior to her death, Little lived with her infant son and her boyfriend, Chris Day, in Day’s mom’s apartment above an antique store at Nebraska and Cherokee streets. A sense of duty to her newborn son motivated Little to get clean and get a more stable job. She died wearing the tattered remains of the uniform from her fast-food job.

But her old life still beckoned. Day says Little worked the stroll in 1990, and he was at her side, himself hustling for clients. He kept an eye on her, and she kept an eye on him. But the night she was abducted, he was locked up in city jail.

“I’ve never been able to go visit her grave,” he says. “I couldn’t face her. Now I guess I’ll have to.”

After February 1991, Burgoon says the St. Louis Major Case Squad came to an agreement with federal law enforcement: The next time the Package Killer struck, local police would seal off the scene so that investigators from the FBI could fly in from Quantico, Virginia, and process all the evidence.

However, the Package Killer never struck again. At least that was the thinking for three decades. Investigators assumed that because dead women stopped showing up in containers along highways, the Package Killer must have stopped taking lives.

But the notion that serial killers never change their methods is more fiction than fact.

Kenna Quinet is a professor emeritus of criminology from the University of Indiana-Indianapolis and one of the few academics who studies serial killers.

“They change their M.O. all the time. They want to kill as many people as they can for as long as they can,” she told the RFT in 2019. “They don’t want to get caught.”

A man who lived on Miami Street in south St. Louis was the police’s prime suspect for the Package Killer murders at the time. Police interviewed him on multiple occasions, showing him pictures of the victims.

“I didn’t worry because I didn’t know any of them,” this man told the RFT nearly 30 years later, adding that he believed that meant the police wouldn’t be able to pin anything on him.

But then came one more photo. “Then there was a blond that I did recognize,” the man said, “and I thought, ‘This is not good.’” In 1992, the Post-Dispatch reported that police had physical evidence connecting the man to Mihan’s murder, likely the blond the man had recognized. Police asked Lincoln County’s prosecuting attorney to bring charges.

Ed Grewach, now the general counsel for the Missouri Gaming Commission, worked for the Lincoln County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office in 1990.

According to Grewach, the only physical evidence connecting Mihan to the man on Miami Street was candle wax found on Mihan’s body. “She was apparently tortured before she was killed,” Grewach says. “This guy had this candle with the same type of wax, but that candle was sold in hundreds of different outlets.” The man was questioned extensively on numerous occasions but never charged.

Throughout the 1990s, Burgoon and other detectives continued working the case, investigating more than 450 leads over three years. Detective Sergeant Jodi Weber, the woman who eventually caught Muehlberg, says that it was only dumb luck that allowed him to evade capture at the time.

“He was never on any detective’s radar,” she says. “More than 50 investigators worked on these cases back in the day, and not one linked anything to him.”

Bill Carson worked the case as a detective in the early 1990s. Now he is chief of police in Maryland Heights, a municipality with only one unsolved homicide in its entire 37-year history: Brenda Pruitt. “Over the years, there were a lot of persons of interest, people that we thought were capable of doing this that we looked at long and hard,” Carson says. “[Muehlberg] was not on our radar.”

In 1995, a series of similar murders occurred in St. Petersburg, Florida, and St. Louis detectives were intrigued enough to travel there to investigate.

They had no idea that the Package Killer had been sentenced to life in prison earlier that year. That case didn’t involve packages or sex workers. It didn’t even involve a woman.

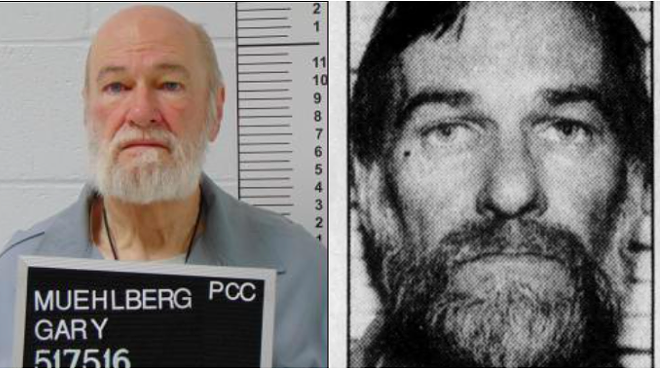

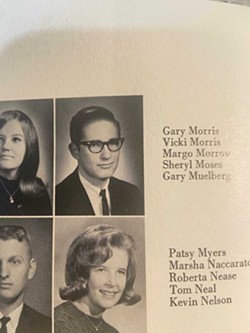

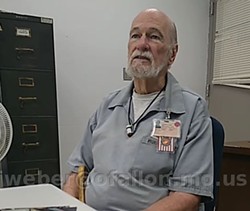

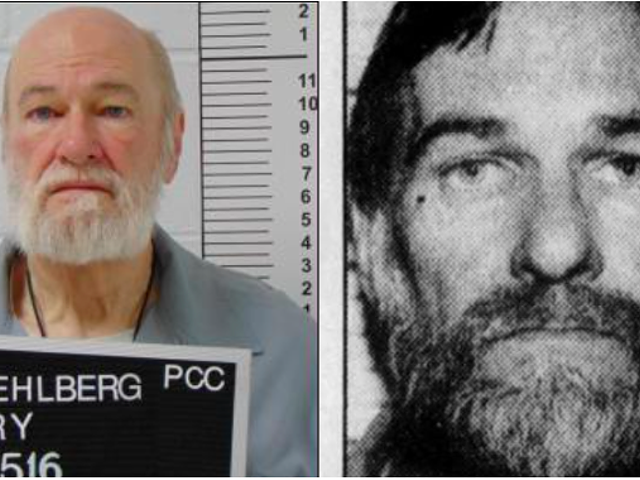

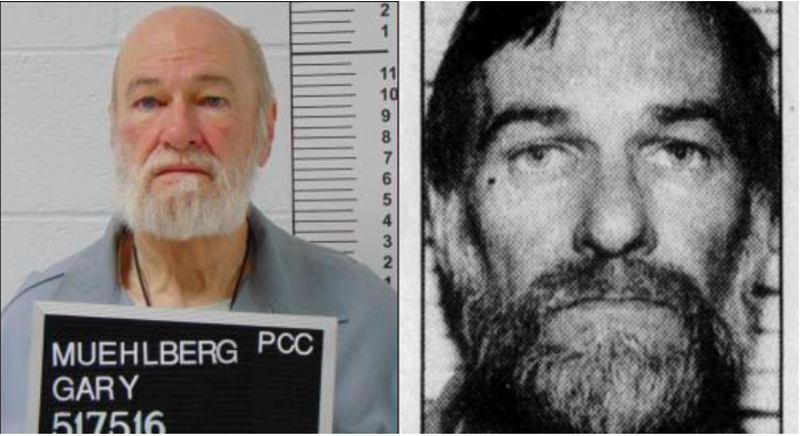

Missouri Department of Corrections, Police Booking Photo

Gary Muehlberg, revealed to be the so-called Package Killer, in March 2020 and in 1993.

Born in 1949, Muehlberg grew up in Bellefontaine Neighbors at a time when the north-county municipality was experiencing rapid growth. Muehlberg’s father, William, had been a policeman until he left to join the military during World War II, earning a Purple Heart after being wounded in the Pacific Theater. He later served as mayor of Bellefontaine Neighbors for one term, 1955 to 1957.

Less is known about Muehlberg’s mother, Palmyra. One of Muehlberg’s ex-wives tells the RFT Christine worked in accounting for a department store.

In 1966, when Gary was 17, the family moved to Salina, Kansas, where his father took a job with an oil company.

Like their father, both Gary and his brother, Ronald, enlisted in the military during the Vietnam War. Gary completed basic training in 1968, though it’s not clear if he was ever deployed overseas. That same year his older brother, who was 21, died during battle in the Mekong Delta.

Gary married for the first time in June 1970. A grainy photo in the Salina Journal announcing the wedding shows a tall Muehlberg flashing a toothy grin. The photo, even in its low resolution, belies the terror that was to come.

In February 1972, Muehlberg was charged with rape, kidnaping and aggravated robbery after breaking into a house in Salina where an 18-year-old girl was home alone. She told police the 23-year-old Muehlberg held her at knifepoint, raped her, and then forced her to accompany him to the bank to withdraw $25 to hand over to him. A judge ordered a mental-competency examination be done on Muehlberg prior to his trial. He was convicted on the robbery charge but acquitted of rape. After spending a month in prison, he was ordered to check into treatment at VA facility in Topeka, though it’s not clear if he ever did.

In January the following year in Salina, a 14-year-old was babysitting even younger children when Muelhberg knocked on the door, asking if he could use the telephone. Brandishing a knife, he told her he was going to rob the house. He then tied up and gagged the young girl, locked her in the bathroom and began filling the bathtub with water. However, a car drove by and a panicked Muehlberg, thinking it was the girl’s parents, fled.

Muehlberg was again charged with aggravated assault.

At trial, Muehlberg’s lawyer claimed that Muehlberg had gone insane at the time of the incident. Muehlberg’s wife, mother and psychiatrist testified for the defense. The jury found Muehlberg guilty, and he was sentenced to five years in prison.

Later in 1973, Muehlberg’s first wife divorced him. He had little contact with his wife or son from that first marriage thereafter. That same year, his mother and father moved back to St. Louis, where his father died of a heart attack soon after.

Upon his release from prison, Muehlberg attended classes at Central Methodist College and Central Missouri State University before moving to St. Louis in the late 1970s.

He married again in 1980. The RFT spoke to the woman, now in her 70s, who was married to Muehlberg for six years before divorcing him in 1986.

She describes Muehlberg as an unremarkable husband who was just “fine” as a father. He always had problems with authority at work, she says. He always resented having to listen to a boss. After their divorce, she says, he wasn’t particularly interested in spending time with his two children, who lived with her but also frequently spent time with Muehlberg’s mother. Muehlberg himself was rarely a presence in their lives.

“I got away from him,” she says. “And I was glad I did after I found out that he killed that guy later on.”

When told why exactly a reporter was calling inquiring about her ex-husband, she adds: “Now I'm really, really glad. I could have been dead.”

In February 1991, the same month that Muehlberg allegedly left Little’s body beside a highway in O’Fallon, Missouri, a fire destroyed a portion of Muehlberg’s home in Bel-Ridge.

The timing of the fire is significant. It occurred in the basement where Muehlberg almost certainly had been keeping the bodies of his victims, in some cases for several months, over the past year. And it likely destroyed important evidence.

In those years, Muehlberg was a regular at the Diner, a restaurant open 24 hours a day in Overland.

“It was your friendly neighborhood coffee shop,” says Larry Kennedy, a regular who got to know Muehlberg. “Aside from the people who went there at night.”

Another regular from that time said at night the diner became host to a “wild crowd” where people avoided telling each other their last names.

Muehlberg was part of the night crowd, Kennedy says.

“You’d see him there at 10, 11, 12 o’clock,” Kennedy says. “And then he’d be there off and on the rest of the night.”

Muehlberg stalked his waitress girlfriend, often posting up at the Diner for the majority of her shift, regulars say. When someone Muehlberg didn’t like came in to eat, Muehlberg would wait outside by his van, peering in until the person he disliked left.

“She was scared to death of him,” Kennedy says.

Deborah Layton, who frequented and later worked at the Diner, says that among the milieu of regulars, Muehlberg rubbed just about everyone the wrong way.

“Gary Muehlberg was crazy. He was always bringing women to his house. He was a very bizarre man. He had bizarre ideas, and he was dirty, like he never cleaned himself,” she says. “He kind of thought he was it, but no one really wanted anything to do with him. From what I learned later, he was picking up waitresses from Waffle Houses and places like that.”

Both Layton and the brother of a woman Muehlberg dated at the time say that Muehlberg often bragged about being an officer in the Freemasons and had a highly inflated sense of his importance. “He always talked about what a secret organization it was and that they helped children so nobody would ever investigate the Masons,” Layton says.

“He was more narcissistic than he was anything,” Kennedy says. Layton adds that Muehlberg was always hanging out with a man who openly displayed his gun and claimed to be a police officer, even though everyone knew he was a security guard. “A rent-a-cop,” Layton says.

Muehlberg had previously worked construction, but in 1993, the 43-year-old was telling others that he was in ailing health. Instead of manual labor, he sold marijuana and dabbled in buying and selling used cars. He later told police that he frequently kept considerable quantities of weed in his basement.

Layton says that in the early ’90s Muehlberg tried to recruit her husband into his burgeoning marijuana business. Muehlberg even showed her husband where he kept his stash.

“He took him over to his house and showed him a false wall in the basement, and said, ‘I got all these bricks of weed. Do you want to help me get rid of them?’” Layton says.

“He was the type of guy who was always sniffing around, trying to make a quick buck,” says another diner regular at the time who asked his name not be used.

In February 1993, Muehlberg spread word around the Diner that he was trying to unload a 1989 Cadillac Fleetwood. Kenneth “Doc” Atchison, another regular, was interested in purchasing the car.

On February 8, Atchison told Kennedy and Layton that he was going over to Muehlberg’s house with $6,000 to buy the car.

Both Kennedy and Layton said they were worried about Atchison going by himself, as Muehlberg had always been a menace and was now involved in large-scale drug dealing.

But Atchison, 57, waved his friends off and headed over to Muehlberg’s house alone.

He was never seen alive again.

Muehlberg, however, showed back up at the diner later that same night, showing off a stack of newly acquired cash.

Atchison’s family filed a missing-persons report, but though Muehlberg was immediately a suspect, police waited to search his home.

In the following days, according to a 1993 police report, Muehlberg contacted at least two people and asked them to construct a plywood box made to his specifications. Investigators would later learn that Muehlberg used the makeshift box to store Atchison’s body.

Muehlberg remained in the house for a week with Atchison’s dead body in the makeshift coffin in the basement.

According to a 1993 police report, he then fled to Illinois, telling his “rent-a-cop” friend that if police searched his basement he would be “locked up the rest of his natural born days.”

From Illinois, he called friends offering them money to go to his house and pretend to do lawn work while checking to see if police were surveilling the premises. He offered one man, Jerry Akers, $20,000 to move the box containing Atchison’s body out of the basement. Akers declined. He asked another man to let his dog out and, while he was at it, move the box containing Atchison out of the basement. The man agreed to let the dog out but left the crude coffin alone.

Muehlberg was arrested one month later, on March 27, 1993. The deputy from the Wayne County Sheriff’s Department in Illinois had no idea he’d handcuffed a serial killer.

During interrogation in St. Louis, Muehlberg admitted to police that Atchison was dead in his basement, though he swore he hadn’t killed him. He began to cooperate with law enforcement, but only because he was trying to pin the murder on his boss at the construction company. Muehlberg insisted that he was being framed.

Prior to police searching his home, Muehlberg told detectives that he had built a “secret room” in the northeast corner of his basement.

“He advised that entry to the room could be gained by pushing on a drywall panel just inside the door leading from the basement to the driveway,” the police report says.

Muehlberg’s house near Endicott Park was leveled at some point in the past two years, but old photos show a forlorn-looking, vinyl-sided ranch far recessed from East Edgar Avenue. Its rear door led directly to the basement. A shoddily overbuilt front porch would have concealed whatever Muehlberg was doing from any prying eyes on the street.

Detectives searching the premises in 1993 found total disarray. Muehlberg had been sleeping on a foldout bed in the living room. Its sheets were soiled, and dirty clothes were strewn about everywhere. In the basement’s “secret room” they found Atchison dead, entombed in the hastily constructed wooden box. “A crude coffin” is how police later described it to the Post-Dispatch.

“They couldn’t get his whole body in there. His feet were sticking out,” Kerry Wisdom, one of the detectives who searched the house, tells the RFT.

Wisdom adds, “This guy must have been a pretty tough old guy because he had a rope around his neck. He’d been stabbed. And he’d been shot. They tried to kill him three different ways.”

Muehlberg had also secured Atchison’s hands in a pair of handcuffs. The car Muehlberg had claimed to want to sell to Atchison turned out to be stolen. After killing the prospective buyer and taking his $6,000 cash, Muehlberg sold it to his boss at the construction company.

During Muehlberg’s 1995 trial, the defense claimed he had been framed by his boss. The jury didn’t buy the implausible story, sentencing Muehlberg to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Doug Sidel, the prosecutor who put Muelhberg in prison in 1995, tells the RFT through a court spokesperson, “We had no information tying him to other crimes.”

Nowadays, the name Gary Muehlberg doesn’t ring much of a bell at the Diner, which operates under a different name, even for some longtime regulars. The loved ones of those he killed, though, still remember. Atchison’s friend Kennedy recalls the moment in the Diner right before Atchison went over to Muehlberg’s house to buy the Cadillac.

“I told him to stand there and wait for me. I was in my work uniform, and I wanted to go up to the house and get a shower and change,” Kennedy says.

Atchison said he didn’t want Kennedy coming along. Kennedy says he realized years later that it was probably because Kennedy and Muehlberg were perpetually at odds.

Kennedy still clearly remembers that night.

“Like it was yesterday,” he says.

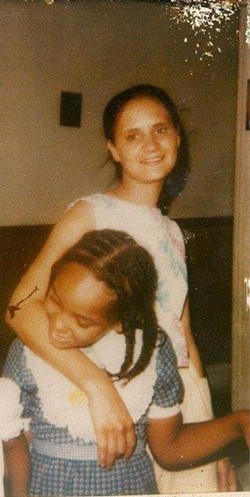

COURTESY CHRIS DAY

Chris Day (left) with his son Chris Day Jr. Day Jr's DNA helped crack the case against Gary Muehlberg.

Despite his life sentence for Atchison’s murder, Muehlberg refused to concede his guilt, penning lengthy longshot legal motions appealing his conviction on the grounds that his trial had been unfair, the jury biased and his defense inadequate.

By 1999, his options for appeal had been exhausted. Muehlberg would be spending the rest of his life in prison.

According to a source familiar with Potosi Correctional Center, Muehlberg has been a “model inmate” who keeps to himself and doesn’t give corrections staff problems.

Muehlberg had been in prison for 29 years when, this summer, Jodi Weber, the detective with the O’Fallon Police Department, showed up to ask him about the murders of Mihan, Pruitt and Little 32 years prior.

O’Fallon, Missouri, is where Sandy Little’s body was dumped in February 1991. Weber is a 22-year veteran of the force and a member of St. Louis County’s Major Case Squad. She arrested infamous killer Pam Hupp. Since 2008 she’s taken a keen interest in the Package Killer cold case.

Detectives describe boxes upon boxes of reports, evidence and other material associated with the case, all of it stored in the Maryland Heights police station. Weber went through it all again, but Muehlberg’s name was nowhere in the countless pages of interviews and witness statements.

Weber says the case became her passion. For 14 years, she worked on it by herself, poring over old reports and re-interviewing key people. But most of all, she was waiting for technology to advance to the point where the remaining pieces of physical evidence from 1990 could be tested for DNA.

Her meticulous investigation crawled along for more than a decade. Then, this summer, a major breakthrough came.

“The lab said, ‘We got a hit. We don’t know who it is, but we got a hit,’” Weber recalls.

It wasn’t long until Weber had a name to match the DNA: Gary Muehlberg.

Maryland Heights Police Chief Bill Carson acknowledges that Muehlberg was not on the radar before that: “It wasn’t until the DNA match came back. Then we started looking at this guy, and all the pieces started falling into place.”

Weber says that because Muehlberg is a prison inmate, his DNA was in the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, waiting for her to connect it to the murders of Mihan, Pruitt and Little.

In July, Sandy Little’s son, Chris Day Jr., was asked to come to the O’Fallon police station where Weber swabbed his nose for a DNA sample.

“Chris, I’ve been working on your mom’s case since 2008,” Weber told him. “And the reason we have you here today is because I’m getting pretty close.”

Day Jr. battles fentanyl addiction. Like his mother had done, his girlfriend works the street. It’s a tragic repetition of history that gives his father, Chris Day, abundant heartache and worry. Weber needed Day Jr.’s help because the DNA that detectives had from his mother had been compromised. They needed a sample from Day Jr. to prove that Little’s DNA was on the same material as Muehlberg’s. By the summer, police sources said they had four pieces of physical evidence from the three victims that connected back to Muehlberg. Weber paid him a visit in Potosi.

“He was surprised to see us after 32 years,” Weber says of that first meeting.

Muehlberg was not in good health, which meant that Weber had to act quickly or risk the man taking his secrets to the grave. “I have to be friends with him,” Weber says. “‘Friends’ is too strong a word. I have to be open to what he says whether I like it or not.”

Muehlberg was initially hesitant to discuss his heinous crimes. “It was hard for him to talk about,” she says, describing him as remorseful. “If you can believe that.”

However, Weber says she developed a rapport with Muehlberg. The second time she interviewed him, he opened up.

She says he described the details of all three gruesome murders, giving her a confession. It almost seemed to give him relief. “He wanted to shake my hand at the end of the interview,” she says. Weber says she had no choice but to extend her hand as well — it was in everyone’s interest that Muehlberg remain willing to keep talking.

She’d soon find out that he had even more to tell her.

Ryan Krull

Detective Sergeant Jodi Weber (center) with the families of three of Muehlberg's alleged victims.

On August 5, friends and relatives of Robyn Mihan, Brenda Pruitt and Sandy Little gathered in a nondescript municipal courtroom in O’Fallon, Missouri, to find out who killed the three women 32 years ago.

Weber had arranged the private event quickly. The family members were only notified the day prior. No one knew for certain what police were going to say, beyond that they had good news. In chairs where trespassers and drunk drivers typically wait to have their infractions adjudicated, the dozen or so family members took seats.

“I wanted to give you guys some answers,” Weber said. “That’s what this is all about.”

Weber said that she’d be sharing the first name and a photo of the man who, though he hadn’t yet been charged, she was certain had killed Mihan, Pruitt and Little. She said that she had interviewed this man in prison twice and that during the second interview, he had confessed.

Several gasped at the word “confessed.”

Weber then asked those assembled to share memories of Mihan, Pruitt and Little.

Geneva Talbot, Sandy Little’s half sister, said that she hates that she never got a chance to really know her sister. “There was a big age gap. She was 20 when she died; I was just 13, a brat annoying her all the time,” she said.

“They were somebody’s sister, daughter, you know, my mother,” Talbot added. “Just because you have the devil on your back doesn’t make you a bad person. My sister was only 20. She could have gotten out of that situation and become an amazing person. We’ll never know.” More than anything, over the last 30 years, the family members had felt their loved ones’ absence.

Brenda Pruitt’s granddaughter, also named Brenda, said that the only things she knows about her grandmother are that she was petite and energetic, always up on her feet, going for early morning walks. She was also clumsy, a trait the younger Brenda inherited.

“And that’s about all I really know about her,” Brenda said. Mostly, they talked about how the murders impacted the families for generations.

“I’m a paranoid person to this day,” Talbot said. “My six-year-old child knows that there’s bad people out there. And I’m teaching her that at six years old because there are bad people out there.” In the wake of his girlfriend’s death, Chris Day remained mired in addiction for decades, serving long stints in prison. Burgoon often visited Day when Day would get locked up. “He’d show me the picture of Sandy he kept with him. He’d say, ‘This isn’t what she’d want,’” Day recalled.

In recent years, Day has settled down, gotten his life on track. “Sandy would be proud of me,” he said.

He felt that her murder being solved would be an important step toward closure, though he was upset his son didn’t make it to the private meeting that day.

“What could he have more important than this?” he asked afterward. Saundra Mihan expressed gratitude to Weber and the other detectives, but she still held bitterness over how the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Department had treated her family in 1990. Lincoln County is where Muehlberg left Robyn’s body alongside a Missouri highway, and deputies told her that Robyn “was not murdered in our fair city. She was just dumped here.” That still smarts.

After everyone had a chance to speak, Weber displayed a photo of Muehlberg, and for the first time the families of Mihan, Pruitt and Little saw the face of the man who took their loved ones.

The group fell silent. The pain that had clung to the families for 30 years now had a face and a name — “Gary.”

The photo of Muehlberg showed him with a neatly trimmed, white goatee, a crown of short white hair around his bald head. He sat upright at the table where Weber interviewed him. He wore a drab prison-issue shirt.

Tommy Mihan asked if Gary was a St. Louis guy.

Weber said he was.

“City or county?” Tommy asked.

Weber, careful with what she could reveal at that moment, said truthfully he had addresses associated with him in both. Weber explained that Gary had been in prison since 1993 for murder. “What kind of murder was it?” one of the family members asked. The question had been awkwardly phrased, but there was no good way to ask it.

Weber explained that the 1993 murder had been different. The victim had been a man, someone Muehlberg knew, the motivation money. After the meeting, Day found himself struggling with complicated feelings. He was grateful to Weber, to Burgoon, to everyone who hadn’t forgotten about Little.

“But he ain’t going to do a day for this,” he said of Muehlberg. “He’s already doing life without. They can’t give him anything else.”

“But at least he ain’t going to hurt no one,” Day’s girlfriend, Jackie, added.

Day was convinced he recognized Muehlberg from crossing paths with him during a stint in state prison.

“He was quiet,” Day said. “He kept to himself.”

After the meeting, Little’s stepsister Barb Studt said, “When it’s all said and done, Sandy’s killer still gets to eat meals, watch TV, read, make friends if you can do that in prison. But he hasn’t suffered, and I don’t know if he will ever suffer enough for robbing the lives from these girls and causing the cascading traumas of the children left behind.”

Talbot says she was sick when she saw Muehlberg’s photo. “I was disturbed that he looked so average. Like a grandpa,” Talbot recalls later. “That face will forever be in my head. I hate his face, and I only saw it for five minutes. Knowing he took the lives of these young women without a piece of remorse. There’s no way he could feel remorse. He’s lived with this just fine for 32 years. I don’t think he ever had a real desire to confess. He just couldn’t deny the hard evidence. I hope he gets death for this. It won’t bring these women back, but an eye for an eye. He deserves no less.”

Gary Muehlberg has children and a sister. His family, to some extent, is still in touch with him. An individual who has interacted with him says that he likely fears the reaction from family members once they learn he didn’t just kill an acquaintance 30 years ago but also tortured and murdered five women, at least three of them young mothers.

Muehlberg’s crimes, by their nature, defy any attempt to make sense of them. Weber says that he has not given any reason that he did what he did other than stating “it was a dark period in his life.” About three weeks after the meeting with the families, Weber went to interview Muehlberg for a third time. He didn’t have much more to say to her.

But then, a few days later, Weber got a letter from Muehlberg. Details are still scant about the content of Muehlberg’s letter, but in it, he confessed to two more murders.

Both women.

Three months after Mihan’s murder, 40-year-old Donna Reitmeyer was out working the stroll with her friend, 24-year-old Sheila Leach. Leach and Reitmeyer had a tight bond, having met while serving time together in prison and now keeping an eye on one another while on the street.

Leach told police that on June 3 she drove Reitmeyer to the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Chippewa Street where Reitmeyer hoped to make some money. Reitmeyer gave her friend a business card and, according to a police report, said that if anything ever happened to her, Leach should tell people about this guy.

The name on the card was Frank, whom Reitmeyer had dated a few times. She was afraid of him because he seemed obsessed with her, stalking her while she was working.

Leach went to a nearby KFC to buy a soda, and when she came out, Reitmeyer was gone. Hours went by without Reitmeyer returning, and the next morning, Leach reported her missing.

Eight days later, Reitmeyer’s body was found in a brown Rubbermaid trash bin near the intersection of South Broadway and Gasconade Street, seven blocks south of the stroll. A price sticker on the bin indicated it had been bought from Beiner Hardware, a store with only two locations in town. Brenda Pruitt would be found in a similar trash bin in October.

There was talk on the street that Reitmeyer had overdosed and the panicked people around her had put her body in the bin. Police had investigated Reitmeyer’s death in connection to the Package Killer, but never had any definitive proof until Muehlberg’s written confession.

Muehlberg says there is a fifth victim as well, a woman he killed in early 1991.

Muehlberg told Weber he doesn’t remember the fifth victim’s name, if he ever even did know. All he can say is that he left her body in a metal container in a self-service car wash.

Weber is now poring through missing-persons reports from that time frame. There’s likely another family out there who for three decades has been left to wonder what happened to their daughter, sister, mother.

Weber wants to bring them some answers.

An earlier version of this story had the incorrect name for Gary Muehlberg's mother. It has been updated. We regret the error.

We welcome tips and feedback. Email the author at [email protected] or follow on Twitter at @RyanWKrull.