In retrospect, he admits that he let his feelings get the better of him. In the sign's place, he put up a postcard on which he'd written the words #WalkAway.

The hashtag has gained popularity with conservatives describing their "walk away moment" from the Democratic Party. Sullivan says he was acting out of frustration, and wanted to "ruffle the feathers" of the people he considered bullies, the leftists he felt had wronged him and his business.

"But that just affiliates me with some other thing that I don't know nothing about," he says now, chuckling. He regrets retorting with the hashtag; he soon took that sign down too.

The conflict continued online. The River Des Peres Yacht Club eventually deleted its Facebook page entirely, but not before Delgado lashed out in the comments, arguing that the Proud Boys' "cash was green" and that she didn't want to mix politics with her business. Her retorts were quickly screen-grabbed and used as additional proof that the Yacht Club was defending a "fascist organization."

Scrolling through the archived messages on the now-deleted Facebook page, Delgado finds a message sent to her inbox: "If the Proud Boys are allowed to meet at your establishment, they will be met with massive, violent resistance with no regard for your business."

After getting that, as well as similar messages, Delgado says she called the cops and shut the store for a day. Before all this, she'd never even heard of the Proud Boys, and suddenly she was getting threatened for serving them sandwiches.

But the Antifa group got its way: Delgado and Sullivan asked the Proud Boys to stop coming by, and the Proud Boy on staff left his job there. The group soon moved to Tuckers.

The damage to the deli had already been done. "It really hurt our business bad," Delgado says. Regulars stopped coming by. A neighborhood group moved its meetings to a different restaurant, and Delgado says she had to cut a full-time position and shorten other shifts to compensate for the lack of business. No matter how good the sandwiches, few people want to be connected to a Proud Boy-supporting deli. Delgado estimates that the Facebook posts and protests drove away half of the shop's July and August sales.

For the loss of business, Delgado blames the anti-fascists and Facebook commenters more than the Proud Boys.

Still, she also doesn't want to see any Proud Boys in her deli again. These days, she gets nervous when a group of young guys enter the restaurant. Sometimes, she asks them: Are you a Proud Boy?

Reached by email, the St. Louis Antifa coalition called the Community Power Network refuses to participate in an interview with "entities that give a voice to fascism."

"A desire to see [the Proud Boys] as individuals with a story is a desire to present them as a non-threat," the group says in a lengthy written response. "We will not work to humanize our people's oppressors."

Its message, basically, is don't be fooled. To St. Louis' anti-fascists, the Proud Boys' insistence that they're a harmless men's club that drinks beer and shares right-wing memes is hardly credible.

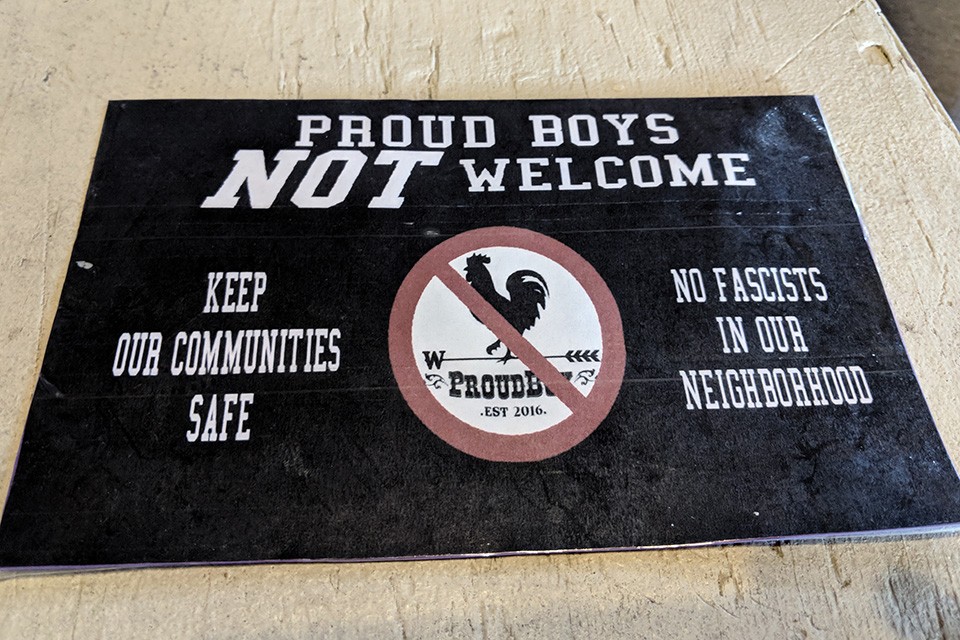

"The Proud Boys are a violent fascist organization that masquerades as a drinking fraternity," the Antifa group contends. "They are known nationally for harassing and attacking women, immigrants, Muslims and those that oppose their beliefs.... We believe it is not only important, but necessary, to take on fascism at the street level with highly organized and militant tactics."

But as the statement continues, the manifesto slides into socialist theory: The Proud Boys, as a group, are "a cog" within global capitalism, and opposition to the right-wing fraternity is just one more fight to be taken up by the working class.

The statement ends on a revolutionary note: "We must collectively oppose all parasites in our neighborhoods, not just the Proud Boys."

The Proud Boys' opponents aren't just groups with Marxist talking points. There's the Southern Poverty Law Center, or SPLC, whose 2017 description of the Proud Boys as a "general hate group" follows them in every documentary and news article. Twitter also suspended numerous Proud Boy accounts prior to the first anniversary of Charlottesville's Unite the Right rally, for what a spokesman claimed were violations of the company's policy against "violent extremist groups."

Keegan Hankes, a research analyst for the Southern Poverty Law Center's Intelligence Project, says the Proud Boys more than deserve their "hate group" label.

"They end up making comments targeted at immigrants, American Muslims,' Hankes says. "And their founder, Gavin McInnes, openly admits he's an Islamophobe."

McInnes co-founded Vice Media before creating the Proud Boys out of whole cloth — taking the name from "Proud of Your Boy," a saccharine show tune from Broadway's adaption of Aladdin. His persona is a pillar of the SPLC's case against the Proud Boys.

In fact, the organization's report on the Proud Boys is largely a dossier of quotations taken from McInnes' various shows, most recently Get Off My Lawn on the conservative online outlet CRTV. It was McInnes who invented the cereal beat-downs and the group's more esoteric habits, such as the encouragement to stop masturbating, or "no wanks."

Hankes acknowledges that the Proud Boys present a confounding image to outsiders, creating an intentional incoherency of internet memes and inside jokes. But within far-right spheres, he warns, the Proud Boys occupy a unique gray area — giving them a membership ripe for recruitment and infiltration by hard-core supremacists.

"They serve as a gateway for so many people who have gone on to other extremism," Hankes says. "The Proud Boys have kicked some of these extreme figures out, and they have let others stay, either out of ignorance or out of willful ignorance."

Hankes mentions that Unite the Right organizer Jason Kessler was a second-degree Proud Boy before his excommunication, and that the Proud Boys' most revered text, Pat Buchanan's Death of the West, is a thinly veiled treatise on danger posed by demographics shifting toward minorities rather than those of European descent.

"The basic argument of that book is that the decline of white birth rates is leading to the death of Western civilization," Hankes says. Similarly, he says, the Proud Boys' noble talk of defending "Western civilization" is both a simplification and a smoke screen.

Further muddying the waters is the Proud Boys' tendency to borrow imagery from quasi-white-nationalist sources: The Fred Perry shirts favored by the Proud Boys were first adopted by mod culture in the 1960s, then taken up by skinheads and later claimed by explicitly anti-Nazi punk bands. (Last year, a Fred Perry spokesman told the Washington Post that the Proud Boys are "counter to our beliefs and the people we work with.")

And then there's the "OK" hand gesture Lasater flashed during his first-degree initiation. According to the fact-checking website Snopes, the gesture was intentionally appropriated in 2017 by trolls hoping to create a "hoax" white-supremacist symbol to enrage liberals. Now the gesture has a life of its own, embraced by an assortment of right-wing personalities and Trump supporters. (Twitter erupted during Brett Kavanaugh's confirmation hearing when an aide appeared to flash it.) A St. Louis trainer who marched with white supremacists in Charlottesville was captured in photos making the same gesture.

But even as their jumble of borrowed ideas and symbols brings them into conflict with the left, the Proud Boys' ongoing battles with Antifa have led them to comity with hate groups on the right.

"The Proud Boys constantly look to seek out the sense of victimhood; they thrive off conflict and controversy," Hankes points out.

Right Wing Leaks, the group that successfully infiltrated the Missouri Proud Boys Facebook group, has its own theory on what's driving the Proud Boys. In a phone interview, a representative (who declines to give his name) argues that the group is offering something its angsty, Trump-supporting members thirst for.

"They're like lost boys," he suggests. "The Proud Boys' ideas don't challenge these men to think critically about any of their behavior or choices. It's just reassuring to be told, 'You've been right all along.'"