Every time she goes to the grocery store, she prays. “I don’t wear gloves, I don’t do any of that, because I just feel like, if that is God’s plan for me, it’s not something I’m going to necessarily try to avoid. I’m just taking it straightforward. If I feel like I have a fever, then I will cover up with a mask, but I haven’t done that. We’ve been going places daily, and we are very healthy. And you can still get it with the mask and the gloves. A lot of people you see still touching their faces and using the same gloves and pulling the mask on and off of their mouths. You can try to be a germ freak and go OCD with this whole thing, but if it wants to strike, it’s going to strike. And if it’s in the air, you have to breathe.”

This is not a new way of thinking, born of the pandemic. “It’s how I live,” she says with a shrug. “I live like that daily.” Before she was able to buy a car, she was “pushing three babies in a stroller down the street, and at night I’d try to get inside fast, before some man could come up.” For courage, she’d remind herself, “If anything is supposed to happen to me, it will happen.” Still, she was scared.

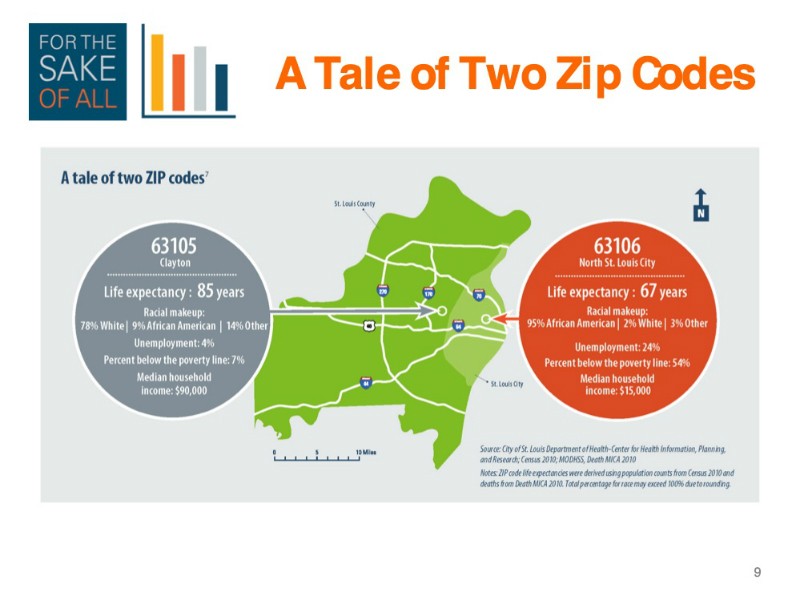

And now she’s even more scared. She knows she lives in 63106, the ZIP code where people’s lives average eighteen years shorter than those of people in 63105 (Clayton). The difference, she figures, is because “there is no hope. There is no money, so that changes hope. You get stressed. There’s a lot of drugs, a lot of alcohol. People turn to different ways to try to survive, and sometimes those ways are horrible.” She pauses to answer Angelino: “It’s a monster! Oh, my!” Then she resumes: “There are programs; the government does eventually reach out. But it’s hard. Say a girl is going to school, and her brother’s in gang violence, and he dies. You just can’t even focus.”

Rogers does focus — she finds every possible opportunity for her kids, and she was just starting to have real dreams for herself. Now, this.

She pulls Angelino close, patting his bottom. “I just want them to find a cure. I feel like, if we can wash our hands with soap and water, they can find a cure! I know we’re against China, but I feel like we really need to pay attention to what China does. First of all, they built a whole hospital for the virus, to contain the virus.” (In fact, they built two in Wuhan alone and more than 30 temporary hospitals.) “And they have been very strict. They have trucks that are sanitizing the air. Here, they had to come close everything down for us to even listen. And the U.S. is spiking numbers higher than where it started!”

What would she say to the nation’s president? “Trump? Bless his heart,” she says, her soft smile hard to read. “Bless his heart. I would just tell him to think about the decisions he’s making for everyone. I’d say, ‘Would you want these same decisions to be made for you and your family?’ The Lysol? I thought that was like something a fifth-grader would say. OK, so now you just really want us to die.” She shakes her head. “I just want to pray for him.”

She thinks reopening is “a horrible idea, because this thing has not been contained. If we are going to reopen now, we should never have closed. It’s only been, like, three weeks, and we have done nothing to get it contained.” It’s not that she loves quarantine, mind you. “I miss being free,” she says, fervent as she’d be in church. “I miss being free, and my kids being able to see their friends and go swimming. I feel like we are caged in, and it’s like if you go outside you are going to die.” She shuttles between being terrified the world is ending and thinking the precautions are obsessive. “I don’t want it to hinder me. If I’m supposed to get the virus, then, ‘God, so be it.’ I don’t want to run from this thing; I don’t want to hide from it. But I also don’t want to not be smart.”

What she did not know, until this interview, is that far more African Americans are being struck down by this virus than whites. (African Americans are dying at 2.7 times the rate for whites, according to data compiled by the APM Research Lab from states reporting by race.) Though Rogers had been cautious, in the back of her head there was always a tiny bit of reassurance: On social media, in the early weeks, she says she saw again and again, “‘Oh, Black people can’t get it.’”

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity project, is telling the story of families in 63106 one by one over the course of the pandemic. Courtnesha Rogers’ story is one of as many as ten that will be shared with a handful of St. Louis media outlets for what will likely be months to come. You can watch this space for further episodes in her life and find an archive of other family stories at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.com.