In October 2007, Toby Weiss, an architectural blogger with an interest in mid-century modern design, wrote a piece about Rizzo's Top of Tower restaurant. Five years later, she uploaded a post about the Tower's broader history to her blog, Built Environment in Layman's Terms, or B.E.L.T.

The two posts have since taken on something of a half-life, constantly referenced and linked during online conversations about the Tower's past, present and future. The comment sections have seen dozens of St. Louisans pouring out memories of the Tower's faded glory; while not always accurate, they're certainly passionate and lively.

Weiss' stories have informed the conversation about the abandoned landmark, something that gives her joy. She calls the ongoing attention to her coverage "beyond fucking cool!"

She writes, "It's heartening to know that people care, both in past-tense (their nostalgia for by-gone glory days) and currently. I'm a research junkie, and knowing there're others like me who get their fix FROM me is a blast! There's no way of knowing what will interest someone down the road. I simply cataloged what mattered to me about St. Louis built environment and the Google bots take care of the rest. I'm thrilled that so many natives care enough to even put something like 'Ackerman Buick sign' in as a search term!"

Weiss' 2012 post in particular answers a lot of questions about how the Tower came to be: planned in 1963, constructed in 1964, with business and residential tenants fully arrived by 1965. While what eventually cropped up was a fascinating, unusual destination for li'l Moline Acres, the site's development never fully realized its potential. For one very big reason.

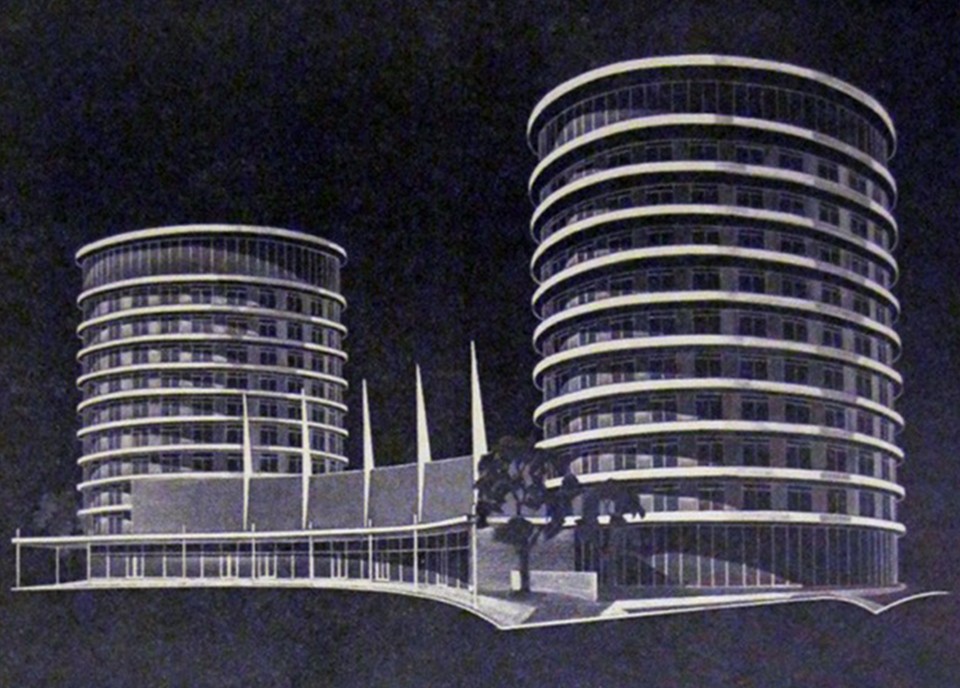

Originally, audaciously, two towers were in the plans.

Architectural sketches Weiss posted on B.E.L.T. show a pair of alike buildings, with a single-story, multi-unit retail plaza running between the two anchors; the towers are described as featuring "St. Louis' first cylindrical apartments," which did come to pass, as did a single tower's completion. Its twin never came to be, presumably due to financial woes on the developer's part. So only a single, cylindrical tower was built, designed by architects George J. Garza & Associates, built by United States Construction Co., and featuring the output of the Laclede Steel Co. But the idea, footprint and ghost of that second tower remain today; looking at the plaza, you can see that the outermost business, Dowling Optometry, has both a slope and curve to its outer wall, with ample space for the missing ghost tower beside it.

Once you're aware of the intended second tower, you can't help but notice its non-presence on the site. But while that second tower wouldn't rise, there was a longtime subterranean life to the space. As Weiss wrote of the building's heyday:

In 1966, the place was 100 percent jumping with at least seven floors of wedge-shaped residential apartments (now condominiums,) each with two sliding doors out to the continuous balcony, with its own swimming pool and gym in the basement. Businesses on the first two floors of the Tower included Alpha Interior Designer, Donton & Sons Tile Co., Figure Trim Reducing, King's Tower Pharmacy and a Missouri State License office.

Shooting off the Tower is a strip of retail facing Hwy 367, long-anchored by Stelmacki Supermarket, a rare, independent grocer still unaffected by the continuous grocery wars. The site slopes down to the West, creating a lower 2nd level building which held the Towers Bowling Lanes and the Lewis & Clark Theater. Occupancy for the complex was robust for 10 years, with an influx of dentists and doctors filling tower spots when others moved out. The Courtesy Sandwich Shop even had a storefront for a bit. The Tower didn't show any longterm vacancies until the late 1970s.

In time, the submerged ground floor would become a pair of clubs: Animal House, an all-ages venue that birthed a significant number of notable St. Louis bands of the '80s and '90s, and Club 367, which was St. Louis' punk-and-metal linchpin during its too-brief lifespan. Eventually, that space became a flea market; today, it's just as condemned as the Tower, with busted police tape across the entryway and police units frequently circling the huge parking lot out back.

Our recent attempts to explore that particular space were foiled on a couple of occasions by the presence of Moline Acres' Finest. But the Tower itself is accessible.