Technically, it was the U.S. Marshals who caught up with Duncan.

The Justice Department's human bloodhounds had been searching more than a year before they cornered Duncan in front of a Tennessee apartment complex. They missed him in Indiana, where agents arrested the friend who'd lent Duncan his identity, and in Mississippi, where he contemplated turning himself in.

By the time they found him in March, he was in his third semester at the University of Memphis, enrolled under the name of his youngest sister's boyfriend. It was one of more than a dozen colleges he attended over a fifteen-year period, using at least three different identities in the process. The financial aid he obtained under his own name was no crime, but federal prosecutors say he ran up a bill of more than $50,000 with the U.S. Department of Education while masquerading as others.

Duncan remembers it was raining the morning of his arrest, and the deputy Marshals had brought with them a fifteen-year-old photo to aid in identification. After brief stops at jails in Tennessee and Oklahoma, they hauled him back to Missouri, where he spent the better part of a year in the Ste. Genevieve County Detention Center, about an hour south of St. Louis.

"I never wanted to be back in here, ever," Duncan says. "I was doing everything I could."

By "here," he means any jail anywhere. He had been locked up multiple times in the past on small-time fraud cases and probation violations, but never for more than a month or so.

Now he is 33, and more than four years have passed since he took the stage at Jefferson College. He wears a Ste. Genevieve County orange jumpsuit, the graying sleeves of a once-white long-underwear shirt stretching toward his thin wrists and long fingers.

He was sentenced in November to three years and nine months in prison after pleading guilty to federal charges of student loan fraud and aggravated identity theft stemming from his time at Jefferson College. Prosecutors say he conspired with his friend to falsely obtain federal financial aid, enroll in classes, apply for student housing and land a campus job. His sentence includes a demand for $57,139 in restitution, which includes $2,000 to the state of Tennessee and $4,529 for a fraudently paid car repair. It might as well be $57 million in light of Duncan's ability to pay it all back.

Someday soon, the Bureau of Prisons will ship him to one of the federal holding facilities it has scattered across the country. Duncan does not know when or where. He tries not to think too far into the future when it comes to things like that.

The past can be a little hazy, too, he says. Suppressing old memories of abuse makes it easier to handle the daily life: "I try to put things in the back of my mind."

But he remembers the play. It was his therapist's idea, he says. He should try doing something fun that was just for himself, she suggested. He had always wanted to be a filmmaker and had done a little acting and writing in high school. When he saw there were open auditions for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, he decided to try out.

"It felt good," Duncan says, his nose wrinkling as he smiles. "I hate to say this, but it felt normal. I don't get a lot of chances to do things that a lot of normal people do — things that normal college students do."

A normal life would have been a small miracle for Duncan.

He is one of Virginia Williams' eighteen children and one of seven who are still alive. He was born three years after a fire torched the family's two-story East St. Louis house and killed eleven of the kids who would have been his older brothers and sisters.

Newspaper stories about the January 11, 1981, tragedy described a blaze that burned with such violence that frantic neighbors and firefighters had no hope of reaching the children, who ranged in age from ten months to eleven years old.

"By then, there was still a little screaming, and I heard what sounded like footsteps," a neighbor told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in the aftermath. "But the fire was too bad and no one came out. By that time, there was no way to get them out."

At the time, Williams had twelve kids. The oldest, who was living with relatives in Mississippi, was the only one left. Williams had left the children alone for hours while she was out gambling with her boyfriend, Will Arthur Jones, who was the father of seven of the dead kids. The doomed siblings suffocated in the smoke.

Nearly 40 years later, the funeral photos of eleven little white caskets arranged side by side are as heart-wrenching as ever.

Williams ultimately pleaded guilty to neglect. A merciful judge, concluding that she had endured enough, sentenced her to a year probation. Williams was pregnant at the time with the first of six children she would give birth to after the fire. Duncan was the youngest of four boys, followed by two sisters.

"I don't know that she's mentally able to really comprehend the effect she's had on us," Duncan says of his mother. "I believe in her mind, she did what she thinks is best."

Williams had a gambling problem and a history of mental illness. Even before the fire, she had been investigated by child welfare agencies, and the horrors of losing eleven of her first twelve children only made things worse.

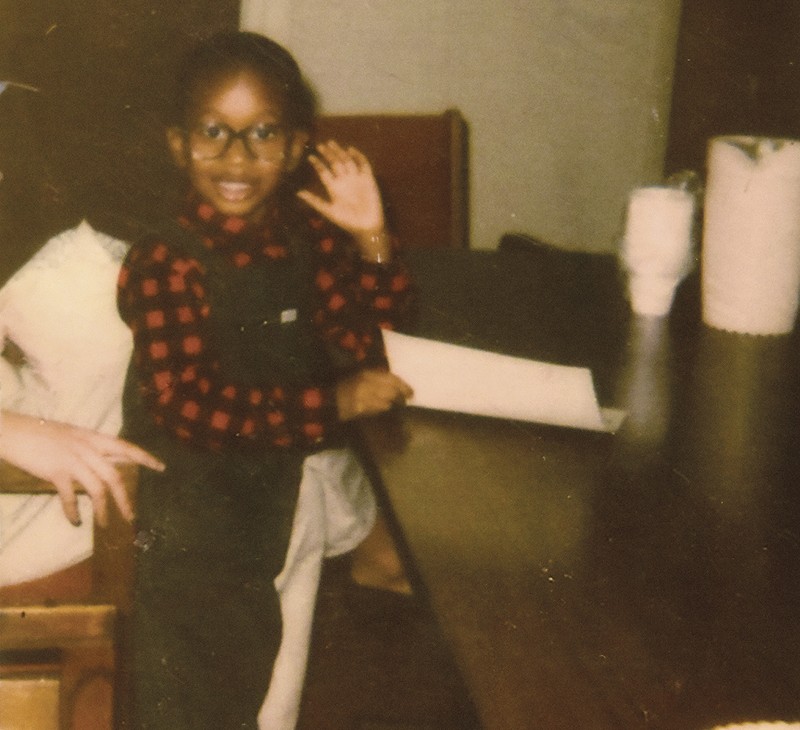

Duncan avoided the worst of it for years; shortly before his first birthday, he was placed with foster parents. A few months later, in 1985, Williams was sentenced to prison in Illinois for child abuse, records show. When Duncan mentions his "mom" and "dad," he is speaking about Alice and Willie Duncan. Born Matthew Jones, he took their name when he turned eighteen. Alice Duncan still remembers when he asked what she would have named her son if she'd had another boy. "Malachi," she answered, thinking little of it. He changed his name the same day.

But Duncan's life with Alice and Willie was marred by lengthy interruptions. The state of Illinois was eager to reunite foster kids with their biological families, and so Duncan started visiting his mother's home on weekends when he was eight or nine. He remembers his father beating his mother on his first night in the house. The culture of violence and abuse in his mother's home was a shock to him.

"It was bad then, but it got worse when I eventually moved in with her," he says.

By the time he was ten, he was living with his biological mother full time. He remembers her whipping him and his brothers with an air conditioner's cord, punching and stomping on them. She would erupt over minor offenses or just a bad night gambling.

"Me and my youngest brother, we were getting beat so much we didn't think we would survive," Duncan says.

They eventually plotted to poison her to death by mixing boric acid into her coffee creamer, he says. "I had it in my head, if we didn't get rid of her, she was going to get rid of us."

The scheme backfired when she discovered the toxic concoction and forced Duncan to eat it, he says. He got sick but survived. Williams declined through a daughter to be interviewed for this story, but she discussed the poisoning incident with a Post-Dispatch reporter in 2001.

"I don't remember," she told the paper. "Maybe that's true... I could have. I probably did to see if [the boys were telling the truth]."

She admitted that she was rough with her boys.

"I whipped them with whatever I got my hands on," she said in the interview. "I didn't want them to come up like me, poor, uneducated and living on the state."

The Post-Dispatch story, which came twenty years after the deadly fire, detailed years of abuse and the toll it had taken on Duncan's brothers, who had lived with her much of their lives. Duncan, however, had returned to the home of his foster parents and, as the story told it, seemed to have escaped their fate.

"Of the four sons, only [Duncan] appears to have emerged relatively unscathed," the paper wrote. "Except for a brief, tumultuous stint with Williams, [Duncan] has lived nearly all of his life in the same foster home, where, he said, he has received guidance, discipline and support. He is a straight-A student with aspirations of going to Yale University."