Duncan just likes school. As a child, along with the physical abuse and mental abuse, he says he was sexually abused, although he refuses to discuss that in detail. Even during the worst days, he could find a refuge in the classroom.

Linda Lawson first noticed him while working as a substitute teacher at George Rogers Clark Junior High School, now a burned-out shell on State Street in East St. Louis. He stood out because he was well-mannered and smart, but he also seemed to be by himself.

"He felt comfortable around adults, because he was an outsider," Lawson remembers. "He was in a rough-and-tumble area. There was something that made me want to help him or protect him."

At the time, she did not know much about his background, other than he was a foster child and the other kids would pick on him. When she asked him why he did not fight back, he replied, "I'm going to let God fight my battles."

Other teachers also recognized something in the skinny boy and gently guided him toward after-school writing programs, where he began to work on stories and plays. He loved fantasies most of all — superheroes and Star Wars — but also tales about kids with seemingly normal lives.

Deborah Granger, an East St. Louis native who now publishes an arts magazine in Los Angeles, returned to her hometown for a couple years in the early 2000s and spearheaded the Miles Davis Arts Festival in honor of the 75th birthday of the city's famous son. While she was in town, Granger helped teach one of the writing programs that had become Duncan's outlet. She lost contact with him in the years that followed. Her voice softens when she learns he is in jail.

"He was a very talented young man," she says, later adding, "That's so sad."

Alice and Willie Duncan still wonder how exactly his path has led to prison.

"As a kid, I never had a problem out of him," Alice Duncan says. "That's why I can't understand."

He spent most of his time in his room reading or watching movies. He tried writing some of his superhero fantasies and made a short film recorded on VHS.

The Duncans, both in their 80s now, fostered 42 children over 34 years by their count. Some stayed only briefly, others for years. Willie Duncan worked as a laborer for Midwest Rubber, and Alice Duncan did a little of everything from warehouse work to selling Avon and caring for senior citizens. It was a solid, middle-class life with occasional vacations. Once, when Duncan was still a young teen, they even went to Disneyland.

Duncan recalls his years in their house as the best in his life, but he grew more rebellious as he reached his later teens. He eventually moved out. During a low point, he stole $8,000 from his foster parents. He says now that he had reconnected with his biological mother and younger sisters and had begun writing bad checks; he says he was trying to help cover the bills. The Duncans were hurt but ultimately forgave him.

"[Alice Duncan] knew what kind of person I was," he says. "She was mostly upset that I hadn't told her what was going on."

In the end, the incident seemed like a lapse from which Duncan would learn a lesson. He had a stroke of luck when his old teacher reached out to him. Lawson had read the Post-Dispatch story about Williams' children after the fire and realized for the first time he was one of those kids.

Lawson had worked with East St. Louis Mayor Carl Officer, and so she connected the two.

Officer hired Duncan at his family's funeral home and was so impressed with his sharp, young employee that he helped him win a full scholarship to Talladega College, a historically black college in Alabama.

But Duncan left Talladega after a few months. He says now he was homesick.

Everyone who knew Duncan as a kid had thought he managed to escape his mother's legacy unscathed, but Lawson says she now realizes that was not the case.

"It's just been a sad situation," she says. "In some ways, the lives of [Duncan] and his brothers were as destroyed as the ones she buried."

Duncan racked up a few convictions for writing bad checks after dropping out of Talladega. It was the beginning of snowballing legal and financial troubles. "Trying to stretch a dollar is what I was doing," he says.

He wrote bad checks to his dentist, the eye doctor and his landlord for rent. One of his first, in March 2010, was for $279.58 worth of groceries at a Schnucks in Illinois.

They were a string of short-term solutions, and they led to lasting problems. It was not long before his criminal record made it impossible to find a job, he says. Duncan had worked for nonprofit social work organizations, using his experience to counsel kids from rough backgrounds. But those avenues were drying up, and even low-level jobs in restaurants had begun to seem out of reach. So he made a deal with an old friend from the East Side named DeMarcus Brewster.

Brewster had his own problems growing up, and he had lived with Duncan off and on when he got older and had nowhere to go.

Duncan claims he hatched the plan after he returned home from one of his bouts in jail and found his possessions had been stolen. He blamed Brewster and says they worked out an arrangement to settle up.

"I said, 'DeMarcus, look, you owe money. I will work under your name. I will give you half the money, and you can stay with me for free,'" Duncan recalls.

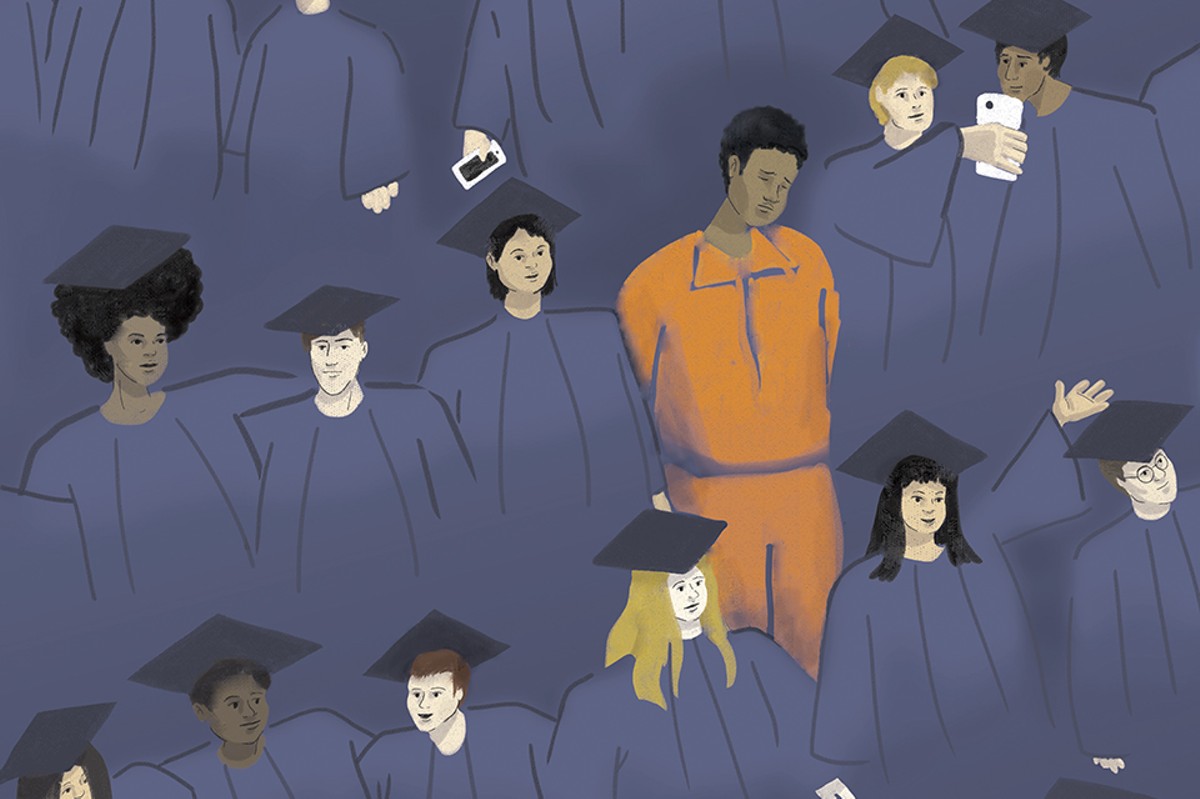

Duncan had continued to pursue college after Talladega, but he was running into problems there, too. Arrests and jail time meant missing classes and often dropping out all together as bounced from one school to another. A probation investigator would later count five colleges and trade schools Duncan had to abandon because of repeated jailings.

He says he wrote his first bad checks to help his younger sister with groceries, and when his biological mother found out, she urged him to write more for cash. To this day, he says he does not know how many he wrote over the years. He did it recklessly, willing the consequences from his mind even as he wrote bad checks to pay court fines for writing bad checks. He was smart enough to know he would get caught but did not see much hope for anything better.

"One might think well as many times as I been locked up how do I get by?" he muses in a letter. "Well I don't."

The bad checks kept popping up like tiny landmines he had buried and temporarily forgotten. All it took was a pissed-off creditor to call the cops. "In my head, I thought I could put the money back, but I kept getting farther and farther behind," he says.

Making things even harder, he had cases on both sides of the Mississippi River. At one one point, his foster parents cashed out bonds they'd saved for his college tuition to settle a case in St. Louis, only to see him delivered directly to jail in Illinois for violating probation, he says. If he was supposed to be staying in Missouri, he was in violation for going home to Illinois, records show. And each time he was locked up, he risked losing whatever job he had managed to get.

"I was trying so hard to turn my life around, and I realized I couldn't do it," he says. "I never was going to make enough money."