A bill filed by Missouri state representative Tony Lovasco would allow eligible patients to try certain psychedelic substances.

Elaine Brewer thought she was out of options. Therapy didn't solve her constant anxiety and depression. Nor did five different antidepressant prescriptions.

Her husband, Heath Brewer, served with Navy Special Operations. In 2011, several of his military colleagues — with whom he and Elaine were friends — died after their military aircraft was shot down in Afghanistan.

The survivor's guilt was crushing.

"I was constantly anxious that my family would be the next one to have that knock on the door," says Elaine Brewer.

After exhausting all options to alleviate her mental distress (therapy, yoga, medication, meditation), she traveled to Mexico on a wellness retreat last July, where she tried psilocybin and MDMA for the first time. The effects were immediate.

"It was like 10 years of therapy in two days," Brewer says.

Brewer discovered what psychedelics experts have long believed, and what scientists are working to confirm — that the drugs can effectively treat mental illness.

State and municipal governments across the country are catching on, too. In 2020, Oregon became the first state to legalize psilocybin, a.k.a. magic mushrooms. Voters approved a ballot measure allowing eligible patients to take psilocybin in supervised, licensed therapy sessions.

A cascade effect ensued. More than a dozen states began considering psychedelic legislation reform, including Missouri.

A new bill sponsored by Representative Tony Lovasco (R-O'Fallon) would allow patients with approved conditions to try certain plant- or fungus-based psychedelics after exhausting all other treatments.

If signed into law by Governor Mike Parson, patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, terminal illness or any serious condition unresponsive to treatment could use these psychedelics. These are people who, like Brewer, seek more than the thrill of a mind-altering "trip."

Brewer's experience in Mexico followed a long effort to quell her anxiety and depression through traditional routes.

She says she felt resentment at "being thrust into a life" she didn't expect to be so difficult. There were the constant funerals for dead military friends, while raising two young boys, now 11 and 3, during her husband's frequent deployments as a bomb technician attached to the Navy SEALs. She quit a job she loved at a veterinary clinic to raise her kids.

But her depression lifted when she took a dose of psilocybin and MDMA, with psychotherapists present, at a private residence in Mexico. The next day, she took 5-MeO-DMT, a psychedelic called "The God Molecule" for its ability to make users feel connected to a divine, higher beauty.

She laid in a bed in a controlled environment, she says, and, with a mask over her eyes, met "her higher self." A sense of comfort washed over her.

"It was really weird," Brewer says. "Like my higher consciousness giving affirmation and love to myself, which I guess brought out a lot of self love and self acceptance."

Brewer has since campaigned to allow Missourians the same opportunity she had. She, along with 14 other witnesses, testified in support of Lovasco's bill during Missouri House of Representatives committee hearings last month.

And yet, members of the Health and Mental Health Policy Committee weren't sold.

"I think the whole thing is rather odd, and I'm concerned that we're even hearing a bill like this," said Representative Brian Seitz, a Republican from Branson who represents Taney County.

Committee Chairman Mike Stephens (R-Bolivar) was also skeptical.

"Because of the history of these substances and our familiarity with it — if not the substance than the stories — we have a very high level of discomfort with this, and I think we're approaching it with great caution," Stephens said.

Some opponents couldn't see past most psychedelics' classification as Schedule I drugs, the same class as heroin.

"To me, that's just absurd," Lovasco tells the RFT. "When you're looking at stuff that is clearly demonstrated not to be dangerous, there's no reason not to let people give it a shot."

Lovasco's bill is the latest attempt to make psychedelics available to certain patients in Missouri. Kansas City state legislator Michael Davis twice filed bills to add psychedelics to Missouri's Right to Try law, but neither passed the committee stage.

Missouri became one of the first to adopt such legislation in 2014. The act allowed terminally ill Missourians to try drugs not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Right to Try wasn't approved at the federal-level until 2018, when Donald Trump signed it into law.

Courtesy Joshua Siegel

Researchers at Washington University map participants' brain activity after they take doses of psilocybin.

Washington University houses one of fewer than 30 academic centers in the U.S. equipped to conduct clinical research with Schedule I substances. With the potential legalization of psychedelic medicine on the horizon, researchers with the school's Program in Psychedelic Research, or PiPeR, hope to pave a way toward a new generation of safe and more effective treatments for psychiatric illness.

"Psychedelics seem to be a rapid antidepressant," says Dr. Joshua Siegel, a founding director of PiPeR, who directs clinical studies on psilocybin. Common antidepressant treatments stimulate plasticity, or the brain's ability to adapt to change, he explains. Psychedelics have the same effect on the emotional parts of our brains, but can spur change much more quickly.

"It allows for shifts in perspectives and behaviors," Siegel says. "That's part of what recovering from depression is — changing your patterns of behavior."

But relief from depression or anxiety is not as simple as one trip, says Larry Shapiro, a psychologist based in St. Louis.

Shapiro assists patients seeking psychedelics' therapeutic effects. He doesn't provide patients with psychedelics, but he helps them undergo therapy sessions before and after their travels out of the country to consume psychedelics.

"The positive outcomes are almost always in conjunction with therapy," Shapiro says. "It's not just, 'Take this and you'll feel better.'"

Brewer incorporated therapy into her Mexico trip. She also started a low-sugar diet with no meat or alcohol.

Before departing, she feared riding on planes and driving in cars, she says, but her fears have vanished.

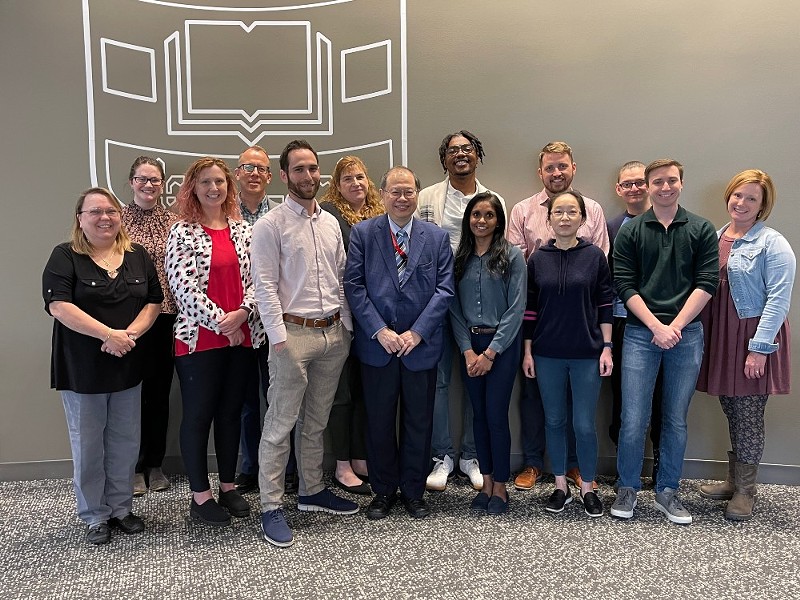

Courtesy Joshua Siegel

From left to right, the team behind Washington University's Program in Psychedelic Research: Teddi Gray, Christine Horan, Ginger Nicol, Eric Lenze, Joshua Siegel, Julie Schweiger, Dean Wong, Demetrius Perry, Subha Subramanian, Jordan McCall, Zhaohua Guo, Avi Klein, Rick Reneau and Vicki Martin.

As Lovasco's bill is now written, eligible patients could use psychedelics at home without supervision. But psychedelics may not be safe for people with severe cardiovascular disease or psychotic disorders, cautions Dr. Ginger Nicol, who cofounded PiPeR with Siegel.

Is Missouri ready for psychedelics? Lovasco says we have a lot of work to do. After a committee hearing in late March, he guessed the bill would need to be revised in order to secure votes. He's looking toward a substitute bill that would allow only for psilocybin use, instead of the broad range of plant and fungus-based substances outlined in the bill's original draft.

"I don't think it's super likely to be signed into law this year as it's a very new issue for Missouri," Lovasco says. "We definitely gotta start the conversation and work towards something we can get consensus on."

But even if Lovasco's bills don't pass, change seems likely to come. And it could be a total game changer.

"If the results of the smaller studies that have been done carry through in our larger studies," Nicol says, "then it will probably be a revolution in mental health and psychiatric pharmacology."