To anyone paying attention, the weeks and months preceding July 2, 1917, contained plenty of evidence that a disaster was on the horizon for East St. Louis.

In the 20th century's first two decades, waves of Southern blacks followed reports of jobs in Northern industrial towns. The positions, they were told, were high-paying, affording the prospect for families to escape the lynchings and servitude that remained in place in the South.

Thousands arrived in East St. Louis, but the hopeful working men found themselves pitted as strikebreakers against the unions, whose lengthy battles with the area's smelting plants and stockyards had resulted in hundreds of white workers walking off the job in protest.

The bitterness of these white workers was further abetted by a city notorious for crime and almost completely given to vice and corruption.

Then a community of about 60,000, East St. Louis sat just over the river from its bigger, boomtown cousin. St. Louis boasted a population of 600,000 and growing. Just 5 percent of its residents were black. East St. Louis' black occupancy, meanwhile, would roughly double in the seven years leading up to 1917 — swelling to about one-sixth of the Illinois city's total residents.

One year prior, the residents of St. Louis passed a ballot measure putting segregation laws on the books. While Illinois had outlawed such formal discrimination, racism and separatism persisted in East St. Louis all the same.

And while factories, smelting plants and railway lines provided employment, East St. Louis was less a city than a collection of lawless fiefdoms stitched together into a bad caricature of a civil government and law enforcement. Factories were intentionally built outside city limits to stiff the city on tax revenue. The mayor was barely a figurehead; the actual power brokers were businessmen and industrialists whose bribes animated their pick of corrupt politicians.

Into this environment entered thousands of black workers; they made their homes just blocks from whites, shopped in the same downtown stores and, crucially, were seen as competition for the same jobs.

The tension of this relatively sudden integration was later described in a congressional investigation, whose final report was delivered one year after the riots.

"White women were afraid to walk the streets at night," the report claimed, characterizing the concerns of East St. Louis' white residents and business leaders. "Negros sat in their laps on street cars; black women crowded them from their seats; they were openly insulted by drunken Negroes. The low saloons and gambling houses were crowded with idle vagabonds; the dance halls in the Negro sections were filled with prostitutes, half clad, in some instances naked, performing lewd dances."

By 1917, tensions between white workers and black strikebreakers intensified. Prominent members of the black community began to see the coming storm all too clearly. That summer, blacks began drilling in secret, gathering arms and preparing for the worst.

On May 28, 1917, a local man named Alexander Flannigan took control of a city council meeting. Flannigan, described in the congressional report as "an attorney of some ability and no character," advised the crowd that blacks couldn't move into the neighborhood if they never reached the front door. "As far as I know," he told the people assembled, "there is no law against mob violence."

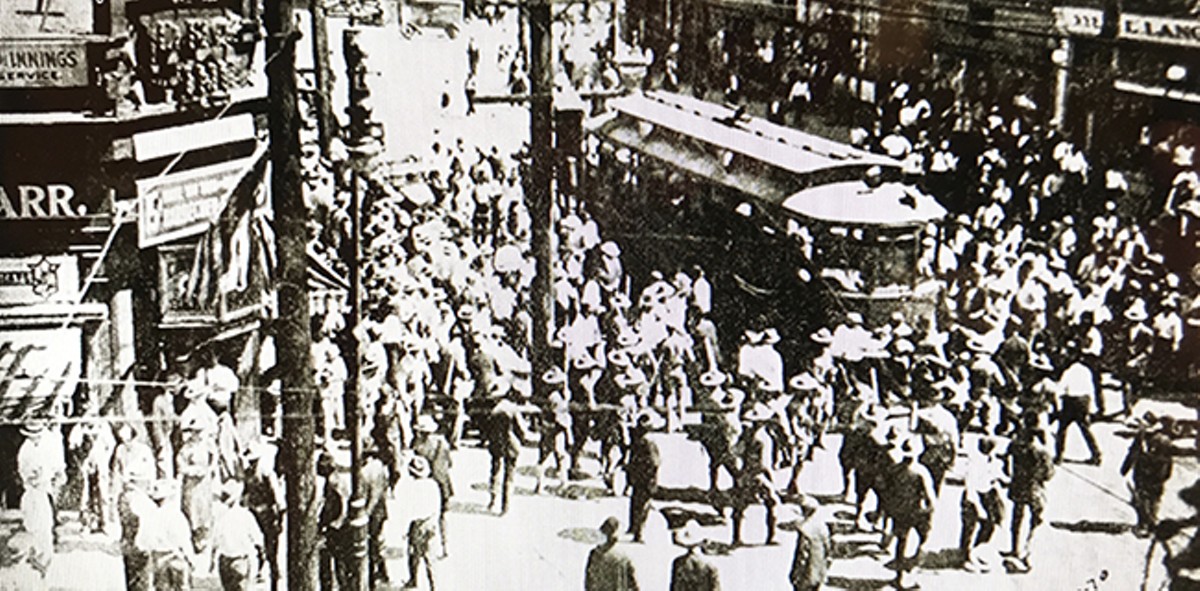

Numbering over 1,000, the white mob fanned into the streets, beating several black bystanders and burning a handful of homes and business. On this occasion, however, soldiers from Illinois National Guard were able to halt the violent tide before people started dying.

Pressure built over the next month. As the Argus indicated, unprovoked beatings happened daily, and the violent attacks increased in frequency and severity. At this point, it would only take a spark to set the whole town ablaze.

One hundred years later, on a recent afternoon, SIUE professor and East St. Louis historian Andrew Theising angles his red Nissan SUV out of the college parking lot and hangs a right onto 8th Street. There are no street signs, however, so Theising counts the blocks until he gets to Bond Avenue.

In 1917, "all this used to be houses," he says, gesturing as he drives to barren stretches of gravel crowded by vegetation and overhanging trees. He pulls up to 10th Street and Bond. It was here, on the evening of July 1, that two plainclothes police officers drove through the intersection in a black Model T Ford.

"There had been some shooting in the neighborhood, over at 17th and Market," Theising recounts. A crowd of several hundred armed blacks, drawn by the ringing of the church bell, arrived to defend the neighborhood from additional drive-by attacks.

"So this unmarked police car came," says Theising, "and it would have been totally dark, no street lights down this way. Right about here is where the officers were shot."

The next day, the blood-spattered and bullet-riddled vehicle sat parked across the street from the police station, and the grim sight attracted a hostile crowd of white men. In his 2008 book Never Been a Time, St. Louis journalist Harper Barnes cites the accounts of newspapermen on the scene who witnessed a sharply dressed lawyer named John Seymour approach the mob.

"[Seymour] said he would be happy to defend anyone who could 'avenge the murders of the two policemen,'" Barnes writes. "The crowd cheered. Policemen standing nearby bantered with the angry white men, and it became apparent to bystanders that they were making it clear, intentionally or not, that they would do nothing that day to stop white men from killing blacks."

Police officers and soldiers would later be implicated for much worse than offering tacit approval to the violence. Two policemen and three soldiers were accused of shooting the arm off a twenty-year-old woman. "Instead of being guardians of the peace," the congressional report noted, "they became part of the mob."

Additional reinforcements from the Illinois National Guard marched into town in the early hours of July 3. The divisions deployed immediately, quelling the most intense violence by placing hundreds of white rioters under arrest.

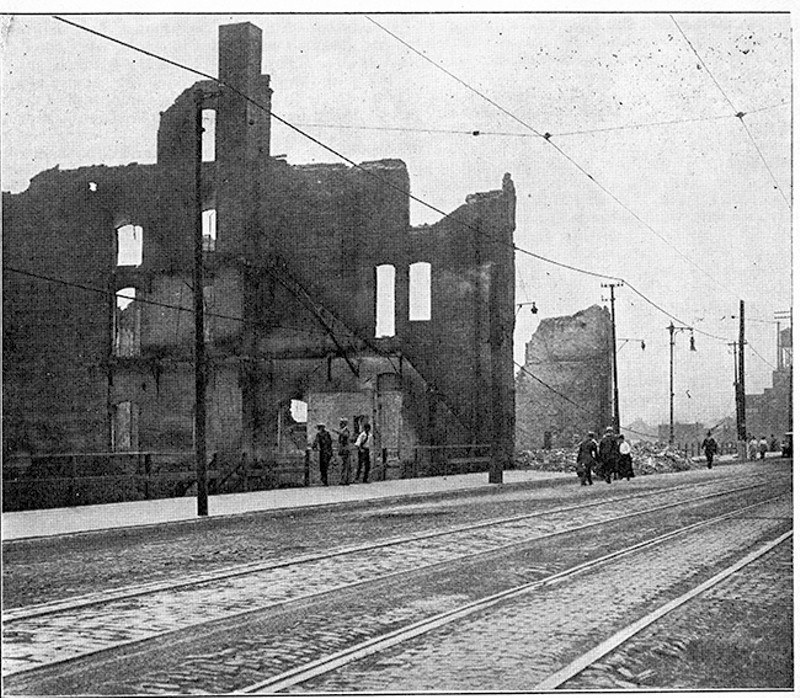

By then, thousands had fled across bridges to Missouri. Some 1,500 blacks sheltered in East St. Louis municipal buildings; when they finally emerged, the city that greeted them must have looked like a hellscape.

More than 300 buildings had been burned, leaving entire neighborhoods decimated. The official death total came to nine white men and 39 black men, women and children. It was an absurdly low estimation. Other accounts placed the black death toll as high as 500. Contemporary historians like Theising believe the number is closer to 100.

"Illinois had a reparation law, and here's where the inability to count bodies really hurt people financially," he notes. "We've tried to find coroner records, and so much of them have been destroyed, if they were even accurate to begin with."

An unknown number of victims were burned inside houses, though it's debatable whether the flames could have completely obliterated the bodies. It's more likely that Cahokia Creek hid many atrocities. In 1917, the waterway ran through the sunken city, coursing under bridges and streets before washing out into the Mississippi.

Theising stops the car at an unassuming intersection that faces an old railway bridge. Piles of grain dropped by passing semis swirl on the pavement. Theising consults a printed map, a list of "sacred sites" he's compiled to help visitors taking self-guided tours.

"I think it was in this very spot," he says, tracing dotted red lines on the paper, which show where the creek once ran. "Either the bodies would have floated underneath us right now, if they were dumped at Broadway, or they were just dumped here. I think they were just dumped from here. This was closer to where people died."

In the fall of 1917, more than 100 people, white and black, were indicted on crimes including murder, rioting and arson. Thirteen people, all black, stood trial for the murder of the two plain-clothed detectives on July 1. Ten were ultimately jailed with fourteen-year sentences. The Illinois Supreme Court upheld the convictions.

But in the end, only a handful of the white mob's ringleaders faced jail time, and police officers and soldiers who were found to have participated in the massacre largely escaped punishment.

That was not true of one black resident who tried to defend his community from the attackers.

A black dentist named Leroy Bundy had organized the self-defense forces that repulsed the white mob from attacking deeper into black neighborhoods. He was accused of causing the riots, and after a sham trial he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Bundy's conviction was overturned in 1920 by the Illinois Supreme Court.

In the end, despite a congressional investigation and widespread outrage at inhumane crimes committed against innocent blacks, there was little justice for the victims. The colonel behind the bungled first response of the Illinois National Guard avoided a court martial and was allowed to resign, an offer similarly extended to city's police chief. East St. Louis mayor Fred Mollman was indicted for "malfeasance in office," but the charge was later dropped. Mollman served out the rest of his two-year term and then retired from politics.

Although a grand jury indicted seven police officers for murder, rioting and conspiracy, state prosecutors ultimately dropped the charges, and instead allowed three officers to plead guilty to rioting and pay a $150 fine. No city or police official faced further punishment for their inaction on July 2 and 3. The mob spirit seemed to melt back into the fabric of East St. Louis. The city moved on.