There are still those who remember the race war.

At first, the task of keeping the stories of East St. Louis' bloodiest summer alive fell to journalists and historians. Although the last decade saw a spike in scholarship on the subject, the strongest contemporary push for preserving the race war's legacy has come from descendants like Ann Walker, whose family arrived in East St. Louis in 1910.

In the early 2000s, Walker won a grant to develop programming that would highlight the African American experience in Illinois. That experience, naturally, included the state's three major race riots of the twentieth century.

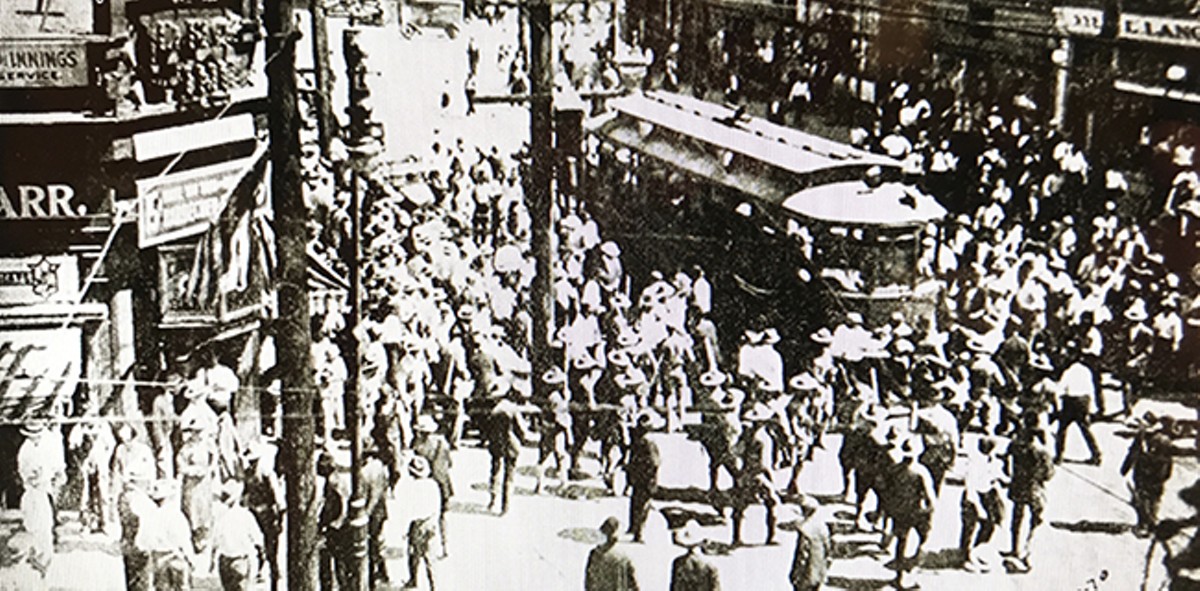

Crisscrossing the state, Walker had found groups of interested community members and amateur historians — at least that was the case in Springfield, where in 1908 a white mob murdered a half-dozen blacks and burned businesses and homes. It was also the case in Chicago, where a massive 1919 race riot was sparked when a white beachgoer struck a swimming black youth in the head with a rock, causing him to drown.

But in East St. Louis, there were blank stares. The city's residents did not know the stories behind the intersections they passed each day, the blood that had been spilled there.

"East St. Louis was a weakest link on the chain, in terms of cultural memory," says Walker. "I'd get these kind of responses: 'I've never heard of that,' or 'Can you tell me more?'"

Walker organized commemorations in East St. Louis, events that ran from 2004 to 2006. But even with her efforts, the Kennedys' work in 1997 and this year's conference, the atrocities remain under the radar for many locals. Even today, East St. Louis still lacks a permanent monument to the events of 1917. Aside from history books, museums and courses in African American studies, few learn of its horrors.

The passage of time has taken much from East St. Louis. Its population dwindled from a peak of more than 80,000 in the 1950s to less than 30,000 today. The city, suggests Walker, is an example of how the horrors of trauma can suppress its transmission.

"My people don't want to talk about it," she says. "They don't want to talk about the race riots, and a lot of that is because the history has been whitewashed. It casts us in a weak light, instead of understanding that having survived all of that is a demonstration of strength, not weakness."

Marvin Teer grew up knowing the difference. His father had been a toddler when his family fled East St. Louis in 1917, but he made sure to pass the stories of resistance and bravery to his own children.

It wasn't just men and women butchered like sheep. There were heroes, like the mortician who delivered refugees to safety in St. Louis — and then returned to Illinois with a hearse full of guns to arm the black defenders.

"Whites came into the black neighborhood after a church was set afire, and they were met with sincere resistance, unexpected resistance," Teer says, recalling one of his father's stories. "It was empowerment. It was saying, 'You will not kill us indiscriminately.'''

Teer doesn't maintain rosy illusions about the events of 1917. The horror that shocked a nation faded quickly, and the succeeding decades brought with them segregation and Jim Crow. Teer's father, Marvin Sr., spent years working in white country clubs that would not accept him or his children.

Still, Teer's father would later become a schoolteacher at Vashon High School and go on to found a transportation company serving seniors. His son is now a state judge who presides over workers' compensation cases.

Marvin O. Teer Sr. died in 2010, at age 97. He may have been the last living survivor of the race war.

"I don't think of it as something epic," explains Teer. The stories of destruction and survival are part of a path, one traced from slavery to the present day. He mentions Santayana's oft-cited quotation — that "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

"It's one thing to remember something," he points out. "It's another to talk about it."