We all missed a lot this year. Too much happened, a decade's worth of chaos cramming into twelve months.

Among the scandals, battles and Congressional hearings, some of the most interesting people — and internet cats — slipped away with too little time allotted to their deaths. That's why the Riverfront Times has again teamed up with our sister papers in Detroit, Cleveland, Orlando, San Antonio, Cincinnati and Tampa to remember a fascinating few who made our world a little more intriguing.

Here you will read of a conspiracy-juicing rock club owner, the activist educator who took on the establishment and won, a stereotype-crushing astrologer, an unfairly maligned ballplayer, the paint-by-numbers guy and St. Louis' profoundly talented and gracious actress Linda Kennedy, who was better than any of us deserved.

It is hard to say what 2020 will bring, but we're sorry these provocateurs, mold-breakers and agitators won't be joining us there.

—Doyle Murphy

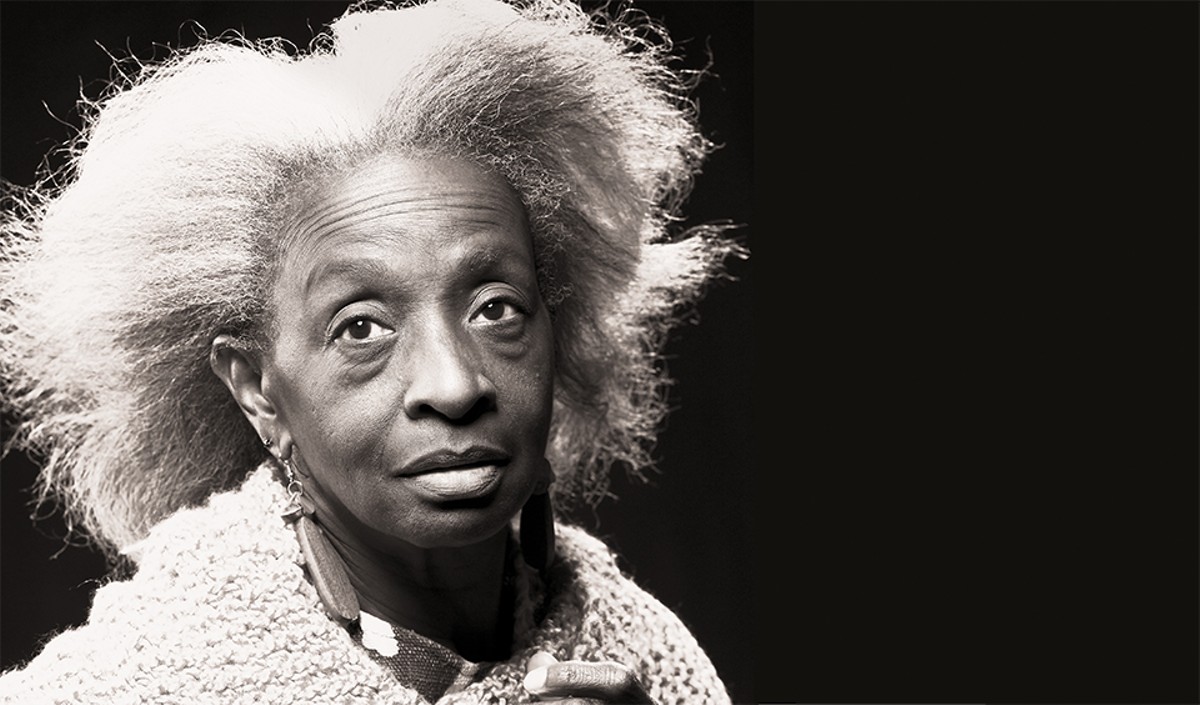

Linda Alton Randall Kennedy, actress

December 5, 1950 - August 16, 2019

In my mind, it's impossible to think of Linda Kennedy without the next thought being the Black Rep, the company she worked with for so many years, so many brilliant performances. Company Founder and Artistic Director Ron Himes called her "the heart and soul of the Black Rep," and even if you only knew her through her many and diverse roles, that much was obvious. She brought that heart and soul to every production, whether as actor, director, writer, choreographer or mentor. For St. Louis audiences, she was the rock-solid, sure thing; if you needed to be coerced into seeing a play you weren't sure about, the phrase "Linda Kennedy is in it," would do the trick.

Kennedy had a gift for a character's physicality. As Iyaoja in Wole Soyinka's Death and the King's Horseman she dominated Himes' horseman with the sudden cocking of her foot. Himes towered over her, and yet Kennedy's smaller frame, draped in sumptuous colors, caught the Grandel Theatre audience's breath in that one movement. She was a defiant South African woman carrying all she owned on her back with her brutal man Boesman death-marching her to a new life, that small frame made smaller by her burden, the weight of Boesman's hand. When she pleaded for a rest with a grating, hopeful "Here?," you ached to take that weight for her, if you could carry it.

And that voice! Kennedy could make it silken or raspy, scathing or thundering. She had an arsenal of laughs, from cackles to great belly laughs that seemed too boisterous for that body. In a monumental production of Romeo and Juliet, she danced the shimmy and swung as only the truly free could. Every character she created had that same force of life glow that illuminated her from within and made that shock of snow-white hair a halo that drew eyes to her no matter where she was onstage.

I knew her as a phenomenal talent, a genuine star who stayed near the ground where she could teach the next generation, but only met her offstage once, and only then in passing. I was both overwhelmed by her presence and amazed that she had the same eyes as the woman onstage. When Himes founded the Black Rep, he did so to give black performers a chance to play the great roles. In St. Louis in the 1970s they weren't wanted in white companies. It was only through Himes' vision that Linda Kennedy was able to practice her craft here, but it was her undeniable skill that saw her eventually break out to every major stage and company in St. Louis. What institutional racism had done she undid with grace, class and God-given and sharply honed talent. The St. Louis theater scene was vastly improved by her hard work over many years. Some rocks don't break. Linda Kennedy is survived by her son, Terrell Randall, Sr., and two grandchildren. The Black Rep will hold a memorial tribute for her at Washington University on January 13, 2020.

— Paul Friswold

Agnès Varda, filmmaker and artist

May 30, 1928 - March 29, 2019

She's sometimes called the mother — or grandmother — of the French New Wave of cinema, but Agnès Varda was more of an Auntie Mame type: whimsical, generous, but nobody's doormat or den mom. Her work was marked by a formal brilliance that influenced her fellow Nouvelle Vague filmmakers, but her fierce humanism — a deep concern for women and workers — buoyed her above the style-obsessed pack.

Her recent collaboration with French muralist JR, Faces Places, gained her more attention in 2018 than she'd seen since the '80s. With her two-toned bowl cut, sneakers and loose tracksuits and pajamas — although, n.b., they were by Gucci — Varda was a welcome haimish presence on the awards season's red carpets, looking like a comfy little kitchen witch among the gazelle-like starlets.

She inhabited the film world in the same way — showing up when and where and exactly how she chose, following no rules but her own. Rather than stick with the narrative films that won her acclaim (Cléo From 5 to 7; One Sings the Other Doesn't) she followed her muse to documentaries (Mur Murs; Jacquot de Nantes). She made lightly dramatized biopics of her loved ones' lives, cast family members as actors and inserted herself into her documentaries; she made dramas, comedies, a sci-fi parable and a feminist musical.

More rule breaking: After losing patience with the traditional dance of studio backing, she founded her own production company to handle her films and those of her husband, Jacques Démy; but she ran the office (located across the street from her home) like a shop, often hand-selling DVDs to visitors or allowing them to watch her editing. "I love being able to have the direct contact with people who are consumers. It's like a peasant, you know, who grows tomatoes and you can come and buy the tomatoes at the farm," she bubbled to Sight + Sound magazine in 2011.

Her final film, Varda by Agnès, was released posthumously in November. It's a self-directed retrospective of her 60-year career, a knowing and playful wink to an oeuvre preoccupied always with human behavior in the face of mortality.

— Jessica Young

Russ Gibb, rock & roll promoter

June 15, 1931 - April 30, 2019

If Iggy Pop is the Godfather of Punk, then Russ Gibb is its uncle.

After working as a Detroit-area schoolteacher, radio DJ and promoter, "Uncle Russ," as he was known, became a major booster of Motor City rock & roll when he founded the Grande Ballroom in 1966, inspired by a visit to San Francisco's Fillmore. The venue became known for booking local acts like the Stooges, Alice Cooper, the Amboy Dukes and the MC5, who served as the venue's house band and recorded its debut Kick Out the Jams live there. That's all in addition to booking national acts like Led Zeppelin, Janis Joplin, Pink Floyd, the Grateful Dead, Cream and the Who, among others, many of whom played some of their first U.S. shows at the venue.

Gibb was involved in other milestones in rock history as well. In 1969, while working as a part-time DJ on WKNR-FM, Gibb took a call from a listener who claimed the Beatles' Paul McCartney died and was replaced with a lookalike and that there were clues in the band's lyrics and album artwork. The conspiracy theory soon went viral. (Perhaps it would come as no surprise that much later in life, Gibb would promote Donald Trump's conspiracy theories about Barack Obama's birth certificate on his blog.)

Gibb closed the venue in 1972. But in the 1980s, he was back in the music business, providing financial backing for the Graystone Hall, a Detroit punk venue. All the while, Gibb worked as a history and media teacher at Dearborn High School; he died in April at 87 of natural causes. The Grande, however, long abandoned and now sporting an MC5 mural, could soon see a new life: It's now owned by Chapel Hill Missionary Baptist Church, who said they might lease it out for events — including possible music concerts.

—Lee DeVito