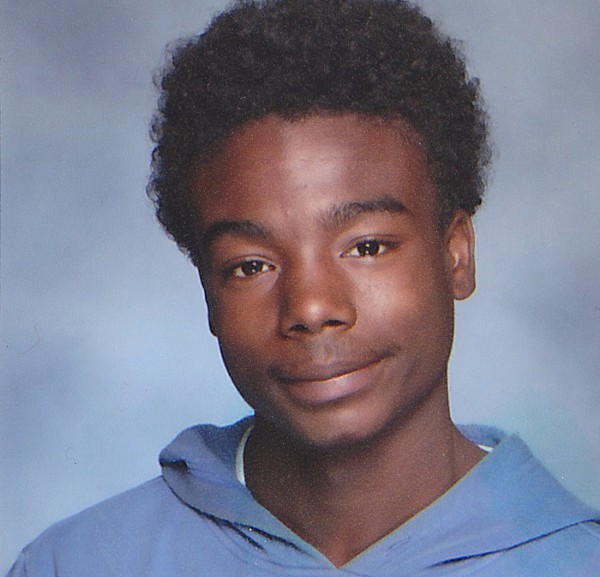

I met Jorell Cleveland for the first time at the Big Brothers Big Sisters’ former office in the Central West End. It was July 1, 2005, and he was about four feet tall with a big afro. He was eight. I thought: There must be some mistake. This kid is so charming and adorable that he couldn’t possibly need mentorship. People must fall at his feet.

We ate Italian at Rossino’s, and he politely answered my questions with one word answers, an upward inflection on the last syllables. Afterwards we watched Jurassic Park on DVD and he said, “This isn’t real because humans didn’t live at the same time as dinosaurs.” When we said goodbye he asked when I’d pick him up again and suggested, “Monday?” which was that same day.

Four years and three months later, Jorell and his father drove 500 miles to Birmingham for my wedding. I was stressed about the event and didn’t sleep the night before. He got up early and ran on the treadmill with me to calm my nerves. I’d left St. Louis by this time and was living in New Jersey, but we’d stayed in touch. Jorell’s family had moved from their home on Gibson Avenue in a pre-gentrified Forest Park Southeast to a big house in Ferguson, which seemed like a step up. We talked a lot about the rapper Gucci Mane.Eleven years, one month and three weeks after we met, Jorell was walking from his house in Ferguson toward a store on Airport Road, where he was going to buy jewelry. It was August 27, 2016 — Saturday afternoon. He had money because he’d been working long hours at a chicken and fish place — that is, when he wasn’t in school or mowing lawns. He took a shortcut through Kinloch, and somewhere along the way a guy or a group of guys ambushed him.

It’s not clear if they knew him or not — or what their dispute was about — but they shot him in the back of the head, and it killed him instantly. His money was still in his pocket when his body was found. Jorell’s sister got the call, and she called Jorell’s girlfriend, and Jorell’s girlfriend’s mother called me. Now back living in St. Louis with my family, I raced over just in time to see his body picked up and taken away. Then a fire truck came and someone sprayed the blood off the asphalt with a giant hose.

Jorell was 19. He never complained, ever, at least not that I heard, which is a weird thing for a human, especially considering he didn’t even have sheets on his bed.

He had lots of siblings, sharing at least one parent with six girls and four other boys. Almost all of them lived together with his dad Joe, a gregarious guy who'd done roofing work before he got injured. Jorell’s mom lived in Arkansas and worked at McDonald’s. His eldest brother Joseph Cleveland Jr. died in January when he had a seizure, fell into a pit filled with water and drowned, which means Joe buried two sons in 2016.

Jorell didn’t expect much. Once, the St. Louis police shot and killed his dog after it broke free of its chain. Another time he randomly found a Books-a-Million gift card in his backyard, and asked me to take him to the St. Louis Mills mall so he could redeem it; turns out the card didn’t have any value. When he was eleven his bike was stolen. In none of these instances did he get angry or rant about revenge. He just accepted these things as part of life.

I offered him money a number of times but he never accepted any (except the time he needed a uniform for his new job). From the start of his teenage years all he wanted to do was work. He borrowed a mower and rang doorbells of houses with tall grass. When it snowed he went door to door with a shovel. He applied for dozens and dozens of jobs over the years with no luck. I’m not exaggerating when I say getting the job at the chicken and fish place was the best thing that ever happened to him. It might not sound like much, but it was a pretty amazing accomplishment considering teenage unemployment rates in north county, and that he never owned a phone or a car. The last thing he ever told me was that he wanted to take my family out to dinner or a movie sometime.

His girlfriend got a job at the chicken and fish place too, and they began spending every day together. Life was good. It wasn’t perfect, though. One day in 2014 when he was getting off the bus a guy started shooting at him. I’m not clear why exactly – Jorell said it was dating back to an earlier dispute involving some guys at a convenience store. The shots missed, but Jorell was booted out of McCluer North and forced to transfer to an alternative school. The administrators didn’t care if the shooting was Jorell’s fault or not; drawing that sort of danger to the bus stop was a threat to other kids.

He wasn’t the best student. He traveled to Memphis with me for my book reading there in 2011, and we had a great time. But when he tried reading the book itself he’d fall asleep. He wasn’t dumb; he knew much more about cars and tech stuff than I did. But it incensed me to learn they were studying Beowulf in his English class; why were kids who couldn’t read at their grade level forced to read fucking Old English?

During the Ferguson riots in 2014 he mostly stayed indoors. He had ideas about race that weren’t what you might expect. In Memphis we drove through some black neighborhoods and he disparaged them. What was with the trash everywhere? Why did black people have to muck up the places they lived? I argued that a history of redlining and discrimination probably had something to do with it, but he wasn’t convinced. He didn’t make excuses for himself or anybody else.

It was inevitable that the sweet kid with an afro would coarsen. As he sprouted, he grew a little mustache, a dead ringer for a young Snoop Doggy Dogg. He blanketed his Facebook page with taunts and threats against adversaries, real and imagined. This annoyed me, but my wife said: When you grow up around aggressive people, you put on a tough façade or people take advantage of you. It’s still not clear to me if it was a façade or not, whether Jorell went over to the dark side or not.

After he was shot at in 2014 my wife and I panicked. I wanted him to move in with us, but before suggesting that we hosted him for a long weekend. I thought it was fun, and the kids loved having him around, but clearly our household was like a foreign country to him – different food, different bedtimes, different M.O. He posted on Facebook that he was lonely and missed his girlfriend. This made me sad; we’d hosted him for a month in New Jersey when he was thirteen, and he had fun going to YMCA camp and swimming. But now he was older and more cynical – just like any teenager anywhere.

I signed him up for therapy at his school, a free program. He went grudgingly but didn’t see the point since his life wasn’t that bad, he said; much worse happened to others. He attended a few sessions with a counselor and then they cut the program. Meanwhile, he and I stopped talking as often. I’d text his girlfriend or his sister’s phone to have him call me, and he responded less and less. I figured he’d gone silent because I often nagged him — about his study habits, about the food he ate. In Memphis for breakfast one time he ordered a plate of pancakes, bacon and eggs, and smothered the whole thing in syrup. I cringed, but in retrospect I should have looked at the bigger picture.

Still, every time we talked, he ended with, “I love you.” It took me aback; “I love you” wasn’t even something I said to my parents much. But I said it too, and it became less awkward. It was only just. He was a guy I loved, a guy so many people loved — his ten siblings and parents and his girlfriend Cherie and his stepmother Tonya and a hundred others.

If life for a kid in a dangerous part of north county was a game, he was attempting to play by its rules. Never mind that they were increasingly byzantine and cruel; he was making a go of it.

Last weekend finally someone picked up the board, shook all the pieces off, and said “game over.” His death was senseless, but his life had meaning.

I can still picture him there in the Big Brothers Big Sisters office, that charming boy who seemed equal to anything, even the mean streets of St. Louis. He’ll always be my little brother.

Ben Westhoff is a St. Louis writer. He's on Twitter @ben_westhoff. If you'd like to help with Cleveland's funeral costs, please see the family's YouCaring site.