This excerpt comes from Ben Westhoff's new book, Little Brother: Love, Tragedy, and My Search For the Truth, about his relationship with his mentee in the Big Brothers Big Sisters program, Jorell Cleveland. When Cleveland was killed near his home in Ferguson in 2016 at age 19, Westhoff set out to find the killer.

I hadn’t seen Jorell in a couple months. It was August 2016, and he’d stopped returning my texts. This was a bit frustrating, but I didn’t take it personally. After all, he’d turned 19 that year, and I figured this was typical teenager stuff.

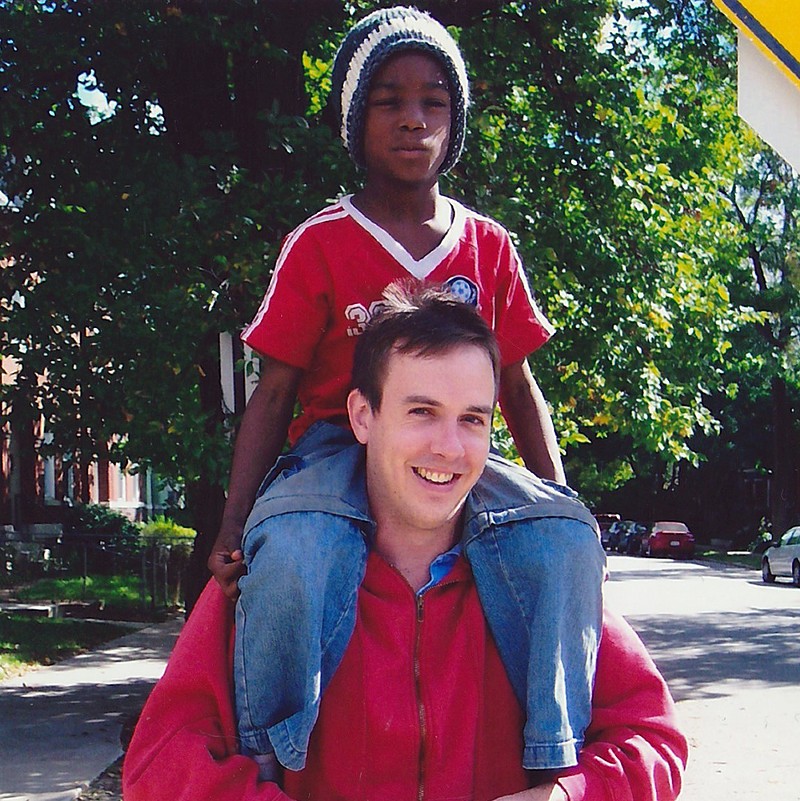

Jorell Cleveland was my Little Brother. The Big Brothers Big Sisters program had paired us 11 years earlier, and I had watched him grow from a shy kid with a big afro who barely stood as high as my chest to a confident, muscled young man who people looked up to. We didn’t share blood, but as far as I was concerned, he was my family.

Our backgrounds could have hardly been more different. I grew up in a tree-canopied St. Paul neighborhood near the University of Minnesota. My mother was an entomologist and my father a doctor. Jorell lived his early years in a poor Arkansas town, and when we first met, his single-parent father was a roofer raising eight children in St. Louis. His mother was in prison back in Arkansas.

I first moved to St. Louis to attend Washington University. I developed an affinity for the city and moved back there at age 26 for my new job at the Riverfront Times. Before long, I felt a need to get involved in a public service program, one where I could actually make a difference. I read a news story about a Big Brothers Big Sisters program focused on children of incarcerated parents.

“For many children, a parent’s incarceration often marks the beginning of a generational cycle of crime,” the article said. “Having a mother in prison often disrupts a child’s environment more than having a father in prison.”

The article touched me, and at Big Brothers Big Sisters, they had an immediate, pressing need, particularly for male volunteers. So, after going through a background check, I was assigned a match. In the early evening of June 30, 2005, I went to the Big Brothers Big Sisters’ offices and met my “Little,” a tiny eight year old who possessed a gigawatt smile.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Jorell Marsay Cleveland,” he said.

“It’s great to meet you,” I said, extending my hand.

“Nice to meet you, too,” he said, shaking it without making eye contact. I thought: There must be some mistake. This kid is so charming and adorable that he couldn’t possibly need mentorship. People must fall at his feet. I was also introduced to his father, Joe, who seemed gregarious and appreciative of my efforts.

For our first outing together, Jorell and I ate dinner at an old-fashioned Italian restaurant called Rossino’s, where the wait staff melted for him, refilling his 7UP glass continually. He couldn’t have been more than 50 pounds.

“Where do you go to school?” I asked.

“Adams,” he said.

“Do you like your teacher?”

“Yes.”

“What grade are you in?”

“Second.”

It continued like this. He politely answered my questions with one-word answers, an upward inflection on the last syllable. When we said goodbye, he asked when I’d pick him up again and suggested, “Monday?” which was that same day.

Jorell craved undivided adult attention. He lived in a crowded household in a dodgy St. Louis neighborhood called Forest Park Southeast. When I drove through the area at night, guys standing on the side of the street tried to flag me down to sell drugs. One time, when Jorell’s dog got off its leash, police shot and killed it.

Despite our biographical differences, we found plenty in common as we explored St. Louis together, trying new burger stands and bowling alleys, and seeing bad movies. I took him to his first Cardinals game at Busch Stadium and got him swimming lessons at the YMCA.

Jorell could be cripplingly shy, his answers to my questions often barely audible. But he had bright eyes, an insatiable curiosity and relentless positivity. He liked to feel the stubble on my face with both of his hands. He was game to do anything, even if it was just hanging out by the pool, listening to rap albums or watching TV in my apartment with my tuxedo cat, Nora.

Not long after we met, I went to pick him up at his home and, upon being invited inside, was shocked by what I saw. “He sleeps on a bare mattress,” I wrote in my journal. “The bedroom door is a frayed blue tarp, and his windows have been broken but never replaced.” But Jorell almost never complained. One time, he found a Books-A-Million gift card in his backyard, and I took him to the mall to redeem it, but the card had no value. Later, his bike was stolen. Still, he didn’t get angry or rant about unfairness. He just accepted life as it was. He never wanted to discuss his mother in prison or any other hardships. I didn’t press him.

A year into our pairing, Jorell told me that his family was moving to a new house in Ferguson. This was a chance for them to get away from the violence and poverty of their city neighborhood. I visited when they moved in, and I was surprised by the size of their six-bedroom home. The backyard was as big as a football field. This was late 2006, the go-go era for real estate, and Jorell’s dad also invested in another house in the area, which he rented out.

This seemed to be a step up for the Cleveland family. Though I didn’t know much about Ferguson, a municipality of 21,000 people, I had middle-class friends who’d been raised in that part of the metro area, known as north county. It was the suburbs, so it had to be safer than the city, right? As I looked around, I saw an area in flux. Some houses on the block were run down, others well maintained. A cute downtown business district was only a short walk away.

Most of the Clevelands’ neighbors were white, but as I would later learn, Ferguson’s population was changing quickly. In the years leading up to Michael Brown’s killing by a white police officer in 2014, the city would become majority Black for the first time, even as the power structure — the lawmakers, the police, the school board — remained white.

It was all part of the evolving demographics of north county, which includes dozens of small towns north of St. Louis. Black families, like the Clevelands, were arriving from the city, while white families were fleeing for suburbs even more distant.

“What do you think?” Jorell asked, showing off his bedroom. I took stock: the only piece of furniture was a blow-up bed, which he shared with three siblings. But the possibilities were endless.

“It’s awesome,” I said.

As a staff writer at the Riverfront Times, I wrote about everything from news to sports to restaurants. But my primary beat was hip-hop, which was blowing up in St. Louis thanks to the success of multiplatinum rapper Nelly, famous for his song “Hot In Herre.” Rap music was also the soundtrack to Jorell’s life and a big part of how we connected. We listened to CDs together and shared notes on albums. Jorell introduced me to new rappers, and I wowed him with stories of interviewing artists whose songs he loved.

Many found it amusing that I, a straightlaced white guy, covered hip-hop, especially considering I neither looked nor acted the part. But it was the music I loved. Plus, it was a great topic for a journalist, as it wielded enormous cultural influence. Rock stars tend to be boringly middle class, but the rappers I interviewed often had cinematic, rags-to-riches stories. Very few journalists were telling their stories, and covering hip-hop gave me a chance to meet people from different backgrounds, as well as an entrée to parts of St. Louis I never would have known otherwise.

Nonetheless, by 2007 St. Louis started feeling small. I wanted to advance my career as a writer and decided the best place to do that was New York City. I rented a small apartment in Brooklyn and began hustling up freelance gigs.

Jorell and I stayed in touch, and we spoke on the phone regularly. I soon began spending time with a woman named Anna, eventually moving in with her in Hoboken, New Jersey. In 2008, 10-year-old Jorell boarded a plane for the first time in his life to visit us for a long weekend. “He enjoyed the flight, watching the cars on the ground turn to ants and drinking Sprite,” I wrote in my journal.

He and Anna got along well. We looked out from the top of the Empire State Building. We explored art galleries in Chelsea. He tried sushi for the first time. He wanted to buy an oversized, novelty $100 bill at a tourist shop, but I talked him out of it. The next summer he came back and stayed with us for five weeks, sleeping on the couch in our duplex and attending a YMCA day camp. Jorell quickly made friends with the other kids in the neighborhood, and even started a dog-walking business with the boy next door, posting signs around the neighborhood.

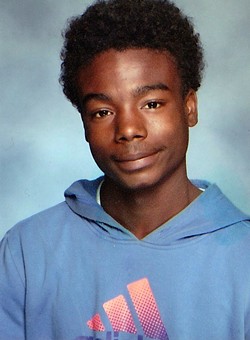

In these years, I saw Jorell searching for an identity, not unlike young people anywhere. One time he sported an afro; the next time cornrows; the next time, his head was shaved. Kids made fun of him at school because of how small he was, and he sometimes got into fights. But I never saw that, and he didn’t often want to talk about the tougher parts of his life. He often relied on small scowls or pursed smiles to express his emotions, except in those rare situations where he felt completely comfortable, when he would explode with waves of roaring laughter.

During a visit to the American Museum of Natural History on his first trip to New York, I snapped a photo of him standing next to a tiger, stuffed and roaring in a glass cage. Jorell posed with his hands up in the air, cowering and pretending to be petrified of the tiger. When I look at the photo now, I see the ideal image of childhood: a happy boy, carefree, totally at ease, unguarded.

In 2014, I moved back to St. Louis yet again, this time with Anna, who’d never lived there, and our two young boys. We moved to be closer to our families; plus, Jorell lived there, and we were thrilled to reconnect.

But upon our October 2014 arrival, St. Louis was in flames. It was the 250th anniversary of the city’s founding, but no one was celebrating. Just two months earlier, Michael Brown had been shot dead in Ferguson. Images of Brown’s body in the street went viral, and local businesses were burned to the ground. Jorell joined the protests and looting on Ferguson’s main thoroughfare. A Justice Department report later detailed how the Ferguson police department targeted African Americans.

Brown’s killing shook me because I saw Jorell in him. Brown was only a year older, and he lived nearby. They were acquaintances; Jorell could have been him.

During this time, I wanted more than ever to be there for Jorell, and through early 2016 I saw him regularly, hanging out and tutoring him with his classwork. But by that summer, when he was 19, he’d grown increasingly difficult to reach. He didn’t have a phone of his own, so I had to go through his dad, his sister Iesha or his girlfriend Danielle. They usually told me he was busy. He had recently returned for his fifth year of high school and spent long hours frying chicken at his job.

When we did get together, I often smelled marijuana on him, and his energy level varied wildly. Sometimes he was practically lifeless, barely listening when I talked and falling asleep in my car. Other times, he bounced with uncharacteristic pep. Though I worried there were things he wasn’t telling me, I figured he probably wasn’t up to anything more scandalous than I’d done at that age.

Plus, I was busy, too. That summer I prepared for the release of my third book, Original Gangstas, a history of Los Angeles gangsta rap in the 1980s and 1990s, as well as the LA riots, gangs, police brutality and crack epidemic that also defined the era. I got to talk to my West Coast childhood heroes, guys like Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre and Ice Cube. Jorell was excited about the book. Though he tended to prefer newer rappers, I’d gotten him into the old West Coast stuff, particularly Snoop Dogg, who was a wiry, menacing Long Beach Crip when he was young. It was striking how much Jorell resembled him, right down to the wispy mustache.

I was working on my book promotion on a Saturday afternoon in August 2016, when I received a phone call from a number I didn’t recognize.

“Hello, Ben? Are you sitting down?”

“Who is this?”

“This is Danielle’s mother.”

This woman — the mother of Jorell’s girlfriend — was someone I’d never spoken with in my life.

“What happened?”

“Jorell has been shot,” she said. “He’s dead.”

After Jorell’s death, I went numb. I remained so through his funeral, which was attended by dozens of friends and family members, and for weeks to come. I had no idea why he was killed, and it appeared that the police didn’t either.

Weeks turned into months, and my shock turned to anger. As the killer continued to go unnamed, that anger turned to guilt. Without knowing why he was killed, I focused the blame on myself. To this day, the guilt hasn’t subsided. I was his Big Brother, after all. The Big Brothers Big Sisters program had no specific requirements for the program — it was our bond that kept us together for over a decade, not any formal obligations — but I believed it was my job to keep him safe. And at that I failed.

One thing seemed certain: His shooting must have been random. The killer must have mistaken him for another person, or he must have accidentally gotten in the middle of someone else’s dispute. He was so good hearted that he couldn’t possibly be tied up in any dangerous business. There was no denying that he had a lot going against him in his life, but he had a big heart, a winning attitude and didn’t seem to possess an ounce of cynicism.

Who could possibly want him dead?

That’s the question I set out to answer in my new book, Little Brother: Love, Tragedy and My Search For the Truth. Doing so required me to find out what was happening behind the scenes in his life — the stuff he never told me. It required me to reconstruct his last months and speak with almost everyone he knew well.

When the police investigation into his death stalled, leaving Jorell’s family desperate for answers, I took matters into my own hands, employing my skillset as an investigative journalist to find the truth. I retraced his steps through dangerous north county streets, tracked down underworld figures and pored over reams of police records.

In the end, what I discovered challenged almost everything I believed about Jorell. It turns out he wasn’t the happy-go-lucky kid I’d always believed him to be. He’d grown paranoid in his final months, answering his front door while clutching a gun. He also had real enemies.

This story is much more than a whodunnit. Seeking the truth about Jorell’s killer required me to understand the troubled history of St. Louis, how discrimination and pervasive poverty has shaped life for millions. It also required me to examine my own choices and mistakes.

I conducted this investigation for Jorell’s family and friends and for myself, to help those who knew him heal. But I held in mind those who live on the margins, whose deaths are seen as insignificant. St. Louis now experiences more violent crime than any other major American city. As measured by per capita homicides per year, it’s 13th in the world — with the top 12 all located in Mexico, Venezuela and Brazil.

We process these deaths through 90-second news clips, if at all. But there’s a lifetime of pain behind each killing. Mothers who lose their children and then lose themselves. Kids who never learn to trust again after their fathers are taken.

I wanted to know what was causing so many homicides. I wanted to understand something we all know exists but rarely interrogate ourselves: Why can’t people in places like Ferguson live in peace?

As a reporter, I had investigated other homicides, but Jorell’s death happened so close to home that I failed to see the full scope for some time. Going after criminals wasn’t new to me but doing so had never felt so personal or presented such challenges to my family. I considered the potential repercussions for my wife and children of chasing an at-large suspect who had killed and could kill again. But I just couldn’t let it go. Jorell’s family needed to know who did this, and so did I.

There were times I was terrified and considered abandoning this quest altogether. But, ultimately, this book became the most rewarding project I’ve ever taken on. That’s because, though it’s a story of tragedy, it’s also one of hope. My research taught me more about Jorell than I’d known during his life, and it helped me understand what made him such a remarkable kid. It brought me closer to his family and closer to my own.

Investigating Jorell’s death also helped me understand the dual worlds that exist in all cities: how wealthy people rarely cross paths with those living in poverty amidst violence. It helped me see, with my own eyes, the inequalities I’d taken for granted. I learned about the systems that conspired against Jorell and how they might be torn down.

The launch event for Ben Westhoff's Little Brother will take place at the Ethical Society of St. Louis (9001 Clayton Road, 314-991-0955) at 7 p.m. Wednesday, May 25.