It is October 2019, and the old Lyon School is dark. It sits on the end of a quiet street in south St. Louis, fenced and forgotten, a three-story brick castle with boarded front doors and a checkerboard of plywood patches over missing windows. During the day, a few neighborhood kids slide through a gap in the fence to play basketball on a beat-up hoop with no net. They run and dribble on weed-cracked asphalt, the same ground touched by a century of St. Louis students.

And then one day something changes — and the lights go on at Lyon School. The hoop disappears and the fence is made sturdier. The kids are replaced by construction workers carrying furniture and climbing up ladders to the soaring slate rooftops.

One year later, the transformation is complete. Entering the former schoolhouse, up the wide stairs and cavernous hallways that carried generations of elementary school students, the classrooms are now bedrooms, kitchens and closets. The principal's office is a studio apartment. The playground has been graded and turned into a parking lot.

Matt Masiel, president of Screaming Eagle Development, opens the door to what used to be Lyon's kindergarten room. The design of the room reminds him of a turret, he says, complete with battlements and a curved wall of five tall windows that nearly reach the ceiling. They flood the room with warm autumn light.

Masiel pauses his tour to gaze out the windows. "This is one of my favorite spaces," he says.

Lyon isn't a trendsetter in St. Louis real estate. Rather, it is among a half-dozen schools that have emerged from vacancy in the last four years under new management and names. Developers like Masiel have taken some of the grandest and oldest structures in St. Louis and released them into the rental market for studios and one- and two-bedroom loft apartments. In general, the projects aim to leverage the building's character and history to attract tenants who can afford rents of about $1,000 per month.

In Lyon, though, the history still feels alive. When Masiel's construction crews began clearing out the former kindergarten, they found painted letters still clinging to the original floorboards, a remnant of some long-ago English lesson.

The developer crouches down and points to the trail of quarter-sized circles — dowel rods inserted into the floor — which trace a neat half-ring that terminates against a wall.

"They called it 'circle time.' It was something they did for kindergarten," he explains, noting that the rest of the circle continues beyond the newly built wall in the unit next door. "This was one big classroom," he marvels, "and they just built it into the ground."

Purpose-built buildings like the Lyon School just aren't made anymore. Built in 1910, at a time when the city was zooming past 700,000 residents, the school's grandiosity reflected that grand purpose, a kind of temple to the mission of educators in a city whose leaders expected its population to keep growing for decades.

More than a century later — now in a city with a population hovering around 300,000 — those expectations are still visible, from the Lyon kindergarten room's built-in seating chart to the massive, twelve-foot-wide hallways designed by famed architect William Ittner, who envisioned the need to contain and move many hundreds of students between classes and assemblies.

Today, those hallways lead to 32 loft apartments.

In 2010, the St. Louis Public School District closed Lyon amid budget cuts and decreasing enrollment, one of eleven schools SLPS closed that year. More followed over the next decade, and year by year, the emptied schools became "surplus properties" listed on the district website. Soon developers began buying up schools in neighborhoods with strong real-estate markets around the Central West End and Soulard.

The historic nature of the buildings come with restrictions. To qualify for certain tax credits, developers must retain the historic character of the structure, which means, for example, that they can't subdivide large hallways into offices or efficiency apartments.

A handful of SLPS surplus properties have been reopened as charter schools or bought by church groups, but of the 21 "success stories" listed by the SLPS website, nine have since reopened as apartments, and more are under development.

Lyon is listed among those success stories. In 2018, Masiel's company purchased the school for $300,000. He went on to spend more than $5 million converting the space into apartments with starting rentals at $920. The price point doesn't scream luxury apartment, though it's still higher to accommodate one or two people than the brick row houses being rented to entire families down the block.

But from the view of St. Louis' struggling school system, and for those still part of it, these success stories aren't storybook endings. Developments like Lyon are an example of the city's adaptation, but also its diminishment. It is a chapter in the serialized epic of erosion authored by each newly closed school, and together they tell the story of a city struggling, and failing, to support a school system that 100 years ago seemed as impressive and durable as the massive brick schoolhouses it oversaw.

And now, it seems like that old story is about to repeat itself all over again.

"This school. I should have paid zero for it."

Matt Masiel's voice echoes off the high trussed ceiling of a two-bedroom apartment that once was part of Lyon's gymnasium. Like other redeveloped schools, the units in Lyon feature somewhat irregular floor plans cut out of the classrooms and available offices. Several units have been built with new staircases and passageways linking separate spaces into new bedrooms. (In one particularly distinctive touch, a studio apartment features a section of original off-green tiling from a wall that had spent the century as part of a boy's bathroom.)

Masiel isn't a newcomer to the historic preservation market, and Lyon isn't his first school redevelopment. In 2019, he and Screaming Eagle completed a $7 million renovation of Nathaniel Hawthorne Elementary School, which became the Hawthorne Apartments.

But Lyon proved to be the far tougher job.

"This was an anchor of bad shit, for lack of a better word," Masiel continues. He notes that his cleaning crews found evidence of human encampments and drug use, as well as the obvious signs that thieves had at some point crawled the structure for its metal components. He says the historic front windows needed to be replaced, a cost of $600,000.

Today, the Lyon Apartments bear many of the touches found in other repurposed St. Louis schoolhouses. Their vast interiors have been scrubbed and repaired, and many of the lofts include preserved chalkboards as stylish reminders for the new residents.

The projects are also buoyed by millions of dollars of public money in the form of tax abatements, a controversial yet widespread form of economic incentive that can zero out a project's real estate taxes for a decade or more. In large part, that abated tax revenue would otherwise go to St. Louis' school system. In fiscal year 2017, the abatements lowered SLPS revenue by about $18 million, according to an analysis by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. In 2018, the incentives accounted for nearly $19 million.

But Masiel insists the abatements are crucial to completing the extensive renovations.

"We had every incentive," Masiel says of the Lyon redevelopment. "We had 100 percent tax abatement for ten years, tax exempt bonds, and still this was a stretch."

Renovating a school can be a valuable investment. Seventeen schools are currently on the SLPS list of surplus properties, and some, such as the 230,000-square-foot colossus that is Dutchtown's former Cleveland High School, come with land that could be part of a multi-use redevelopment.

Of course, the land comes with a school-sized catch. Masiel might be drawn to the potential development sites available through Cleveland's proximity to Grand Avenue, but even if he bought the school, he'd have to take on the expensive rehab before building anything else.

"They won't sell you the building unless you have a plan to do the building," Masiel says, describing his experience with SLPS. "I'd love to do Cleveland, but it's 200,000 square feet — it's Lyon times four. You're talking about a $30 million project before you can do anything outside that."

He adds, "If you gave me Cleveland, I couldn't make it work."

But the competition for developable schools is growing tighter. Advantes Development has bought and renovated three schools, including luxury apartments in the former Lafayette School in Soulard, and is in the process of turning the former Wilkinson School in Ellendale into 34 loft units. Garcia Properties turned Gratiot School on the edge of Dogtown into a 25-unit apartment complex.

Schools in north city haven't been entirely overlooked, with several reopened as charter schools or bought by church groups. But only two of the nine completed loft-to-school conversions featured in the SLPS "success stories" are located north of Delmar.

That trend may change. In Old North St. Louis, the former Webster School is targeted for transformation into senior apartments, and its developer, Lewis McKinney of LMAC Holdings, obtained even more incentives than Masiel did with Lyon: The $12 million project will get $8 million in federal low-income housing tax credits and a $9.4 million investment from the St. Louis Equity Fund, the Post-Dispatch reported this month.

With the cache of SLPS properties continuing to age and deteriorate, Masiel isn't sure if he'll buy a third school. "The fact is," he notes, "the schools out there have had time to be downgraded, or broken into." It's a lesson he took from renovating Lyon, which had stood empty only a few years more than Hawthorne, but had suffered significantly more damage.

Then again, St. Louis' secondhand school market has a tendency to expand.

"It'll be interesting when they do the new round of closings," he grants. "You never know."

Indeed, by the time Masiel's crew started renovations at Lyon, a new wave of school closings was on the horizon. In December 2019, for the first time in St. Louis Public Schools' history, state data revealed that the district had fallen below 20,000 full-time K-12 students.

News of that ignominious benchmark was first reported by the Post-Dispatch's Blythe Bernhard and Janelle O'Dea. The December 12, 2019, story laying out the brutal facts facing the disctrict featured an ominous prediction attributed to a district spokeswoman:

"Any St. Louis school with fewer than 200 students — or about two dozen of the district's 68 buildings — could be under consideration for closure this spring," Bernhard and O'Dea reported.

School closures have long been a reality for St. Louis, and it reflects the trends that have seen SLPS go from being the largest school district in the state to the fourth in less than a decade. The district's last mass school closure occurred in 2010, shutting Lyon and ten other schools in a sweep that reduced the district's total number of operating buildings to 75.

During the next ten years, the closures continued intermittently. By 2020, SLPS has reduced its holdings to 68 buildings. (By comparison, the Rockwood School District — which last year opened a new 600-capacity school in Eureka — uses just 29 buildings to serve 21,000 students.)

In response to the Post-Dispatch's December 12, 2019, report, SLPS Superintendent Kelvin Adams sent a reassuring letter to the district's suddenly closure-panicked principals. The letter would be the subject of a Bernhard follow-up story the next day, as she reported the letter both "assured them that no schools have been identified for closure" and announced a series of town hall meetings to get community feedback on the district's future consolidation plans.

The town halls convened, and months passed. Then, along with everything else, the process was disrupted by COVID-19. In March, SLPS temporarily closed all of its buildings as the pandemic wreaked havoc on teachers, parents and students.

But the pandemic only paused the consolidation process. On December 1, 2020, Superintendent Adams walked to a podium in a school assembly room. Recommendations in hand, he faced the SLPS school board with an update about the district's stance on school closures.

"The notion of looking at our past is really a reminder of what we own, and what remains beyond our institutional reach," he began.

"It is our part tonight to remind the board, and the public, what they are responsible for."

Before presenting the board with his recommendations, Adams digressed into the storied history of St. Louis schools. He mentioned the Des Peres School in Carondelet, which in 1873 became the first publicly funded kindergarten in the United States. He praised Sumner High School, founded in 1875 as the first school for Black students west of the Mississippi, and which counts among its alumni Chuck Berry, Arthur Ashe, Tina Turner and Dick Gregory.

After a few more minutes of preamble, Adams finally dropped the bad news: His proposal called for closing outright a total of ten schools, including Sumner, while converting an eleventh, Carnahan High School, into a middle school. Seven of the schools to be closed are located in north St. Louis.

The proposed closures, effective 2021, would impact a total of 2,200 students and 299 employees, Adams said, though he contends staff members could join schools struggling to fill teacher and support positions. According to the proposal, the savings derived from the closures would go to increasing all school budgets, expanding access to elective courses and fully staffing the remaining schools with nurses, social workers, counselors, security officers and "family community specialists."

In his remarks to the board, Adams sounded all too aware of how the news was likely to land with the families of those students and staff now facing relocation.

"If the board and the public look at this as a way of destroying the past then I think there is a misnomer here," he said and asked that the community "not look at this like school consolidation or closing, but what we are doing to allot our resources to better support our schools."

But semantics aside, Adams also gave the board a 38-page report that set the crisis in stark red numbers. He'd tracked just how expensive inefficiency can be when it means operating a school built to hold 1,500 with a student body diving below 200. At Sumner, with an enrollment of 205, the cost is about $14,000 per student, Adams found; for Northwest's 187 students, the cost comes to more than $17,000.

See Also: St. Louis Superintendent: 'Losing a School Is Like a Death'

Adams faced pushback. During a question-and-answer session, board Vice President Susan Jones noted that Vashon High School would be the only neighborhood school left in north city under the proposed consolidation. Other board members raised concerns that charter schools, which are publicly funded but independently operated, would use the closures as an opportunity to absorb local students, further weakening the SLPS system.

But SLPS schools are missing too many students, Adams replied. Some buildings are already operating with multiple floors and wings shut down, and even then, the SLPS is failing to find enough teachers to staff its many schools. Adams argued that the district's low salaries make it "incredibly hard to recruit people." As an example, he described an SLPS principal "at one of our premier schools" who had been pressed into service as a math teacher earlier this year when the person hired for the job "left a week before school started."

The board meeting lasted more than two hours, with several members voicing concern about whether the scheduled vote for December 15, just two weeks later, would give the community sufficient time to respond and prepare.

For his part, Adams pressed for quick action, and reminded the board of the town halls that had been conducted in January and February. He pointed to the stark numbers on enrollment, reflecting the underlying reality of the economic and social divisions between St. Louis' north and south — and the decades-long pull of population away from north city. "Resources have been divested away from this area of the city, and we bear the brunt of it," Adams said, but he added, "We can't walk away from facts."

Still, Adams described the proposal as a kind of compromise, one that would keep open several underperforming schools in neighborhoods that would otherwise lack any school presence.

"Frankly, I'm giving you ten schools," Adams told the board. "I could have made recommendation for twenty schools, very easily."

He paused and repeated himself: "Very easily."

If architect William Ittner designed Lyon like a castle, then Euclid School in Fountain Park was crafted like one of the city's German breweries, a towering structure of deep red brick and Romanesque columns. Opened in 1890, the school was designed by German American August Kirchner. It's been closed since 2007.

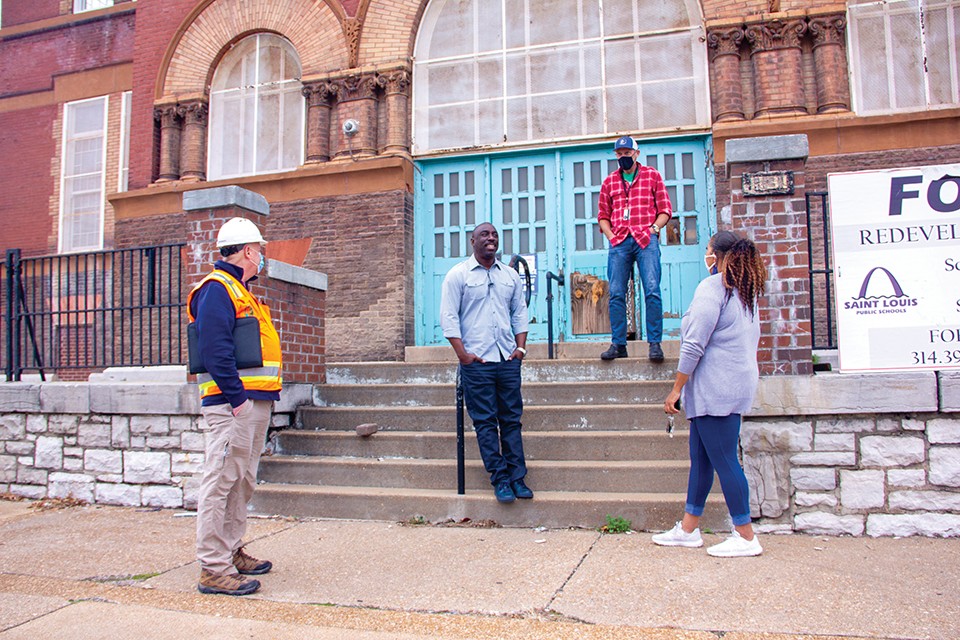

On an overcast afternoon, a cold wind blows against a small tour group assembled beneath the round Roman arches at Euclid's grand entryway. Inside the darkened hallways, they take careful, crunching steps over the piles of paint flakes and pieces of the ceiling. They peer at event flyers and homework assignments still pinned to bulletin boards.

Among them is 18th Ward Democratic Committeewoman Yolonda Yancie, who attended Euclid through second grade in the early 1980s. To her surprise, she still remembers the way to her old kindergarten classroom.

"Oh my god," she says, stepping into the blue-painted room. She walks over the glass-strewn purple carpet to the curved wall of windows overlooking the schoolyard where she learned to play double dutch at recess.

"I remember the circle room," she says. "Ms. Valentine was my favorite teacher. She set the groundwork for who I am today. That's how I knew exactly where to come."

It's not just the memories of a beloved former teacher that strike Yancie; it's remembering that this kind of neighborhood school has all but disappeared in St. Louis. "It's really not fair," Yancie says. "It's the community that sets the tone for the children."

Euclid is among seventeen buildings currently on the SLPS list of surplus properties. At a time when ten more schools may soon be shuttered, it serves as an example of what happens to the body of a structure whose bones are approaching a state of terminal decomposition.

Despite the building's age and how long it's been closed, Kevin Bryant, of Kingsway Development, comes away from the tour with optimism. He envisions turning the building into senior apartments, a form of affordable housing that would open opportunities for tax credits and other incentives.

"The biggest thing this Euclid is suffering from is a roof," Bryant observes. "The roof is going to do what a roof does after years of neglect, but roof aside, I'm a fan of the architecture. Just the strength of that building."

Euclid isn't part of Bryant's major project one mile to the south along Delmar Boulevard. There, the developer has spent years assembling land and financing for an $84 million project that seeks to connect a corridor of ignored north-city neighborhoods to the thriving Central West End.

Weeks after the tour, in a follow-up interview, Bryant confirms that he has signed a contract on the school. A school redeveloper would be something of a fitting role for Bryant, who as a child attended University City's Nathaniel Hawthorne Elementary, the same school Masiel and Screaming Eagle recently converted to loft apartments.

Turning Euclid into apartments would be Bryant's first school redevelopment. After that first tour, he returned for more exploratory trips through its hallways and descents into its dark basement, finding the boiler room and "little hidden passages where they delivered coal."

"It's just rock solid. You just don't see this kind of construction and architecture anymore, no one can even afford it," he says. But it's more than just the building's strength and potential for what preservationists call "adaptive reuse." There's sadness, too, he points out, in seeing the physical epilogue to the long decline of St. Louis' educational system.

Like Lyon and Sumner and the others slated for closure, these schools represent an inheritance left to rot. Behind the beautiful architecture, buildings that were intended to preserve the best of the previous century are doomed to stand abandoned, monuments to monumental loss.

"This is the kind of structure where we committed our children. It was just that important an institution in our community," Bryant says of Euclid.

"And now," he adds, "it's a ghost town."

Update: During a December 15 meeting of the St. Louis Public School Board, members voted to delay a vote on the proposed school closures until January 15.