For about six days in 1918, William M. Riley was the first elected Black lawmaker in Missouri's state legislature.

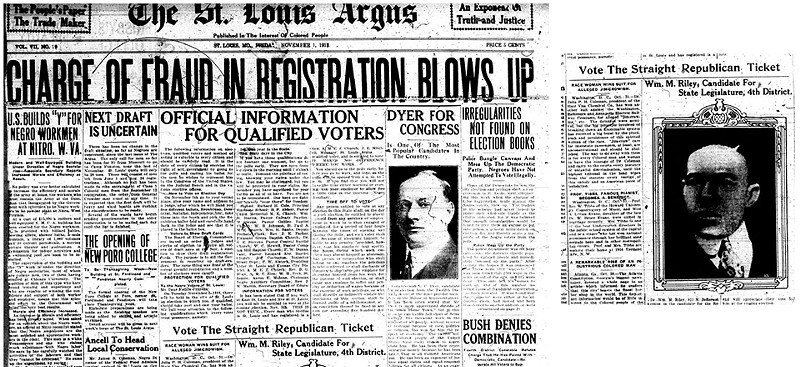

The St. Louis optometrist's win in the race for state representative, on a Republican ticket, made headlines across the country as newspapers detailed his victory despite a racist backlash of white voters who accused local Republican leaders of concealing Riley's race.

But those same newspapers soon had a different story to tell: Days after the election, the results were overturned. Instead of a breaker of barriers, his name etched in history, Riley was deemed the loser. His story faded from public view, even within the city he so briefly represented.

But the legacy of Missouri's almost-first Black lawmaker deserves so much more than empty pages in our history books. That's the position of Nathan Elwood, director of the Missouri Legislative Library in Jefferson City, who in the summer of 2021 was clicking through newspaper archives when he stumbled across a cryptic reference to a bizarre election more than a century in the past.

Digging further, Elwood found accounts of Riley's 1918 win in multiple newspapers — and he realized that he had rediscovered something important, and forgotten, about Missouri's history.

"It was a moment in the state's electoral history where things could have been very different," Elwood says now. "This was national news. I have found reporting on his victory as far as California, New York, Philadelphia. This was a monumental shift for Missouri."

But after months of digging, Elwood says his research turned up no published references to Riley after 1922, even among the region's growing Black political movements in the following decades.

Instead, Elwood says Riley "basically vanishes" from all available written accounts.

"I just found that very striking," he observes, "that someone who was so significant — who was reported on nationally — could in just a few years disappear, essentially."

Elwood maintains that Riley's story is more relevant than ever. More than two dozen newspaper accounts, which Elwood shared with the Riverfront Times, help trace the story of a successful business owner whose campaign for elected office pushed against the color barrier in Missouri — and won.

'Another step toward the goal of Democracy'

Who was William M. Riley? Among his earliest appearances in print is a June 1918 newspaper story in the Black-owned St. Louis Argus; the story describes him as a Kansas native who moved to St. Louis after completing his studies as an optometrist at Langston University in Oklahoma. The move proved a success for Riley, who established multiple offices and other businesses, including a jewelry store.

However, his entry into politics came at a time of crisis, notably World War I still raging in Europe. While there's never been a time when it was easy to be a Black politician, 1918 was an especially difficult year. Riley's St. Louis was caught in an era of intense racism and pushback to integration — with opposition coming both by ballot and bullet.

Just two years earlier, in 1916, St. Louis voters had approved legal segregation through a ballot initiative that made it illegal for anyone to live on a block where 75 percent of occupants were a different race. In 1917, East St. Louis burned as mobs of white workers, their rage abetted by police, massacred dozens of Black residents in an atrocity that shocked the nation.

But there was optimism around Riley's candidacy. The Argus described him in glowing terms.

"A man of his type is capable of fighting for the rights of his people," the paper editorialized. "Honesty and perseverance is his motto. He is capable and his character commends him to the honor. His election will be another step toward the goal of Democracy."

Riley went on to win his August primary, setting himself up to compete in a November general election that featured three candidates from the Democratic Party and three from the Republicans. At the time, the general election was structured to send voters' top three picks to the Missouri House, and the initial results indicated a Republican landslide: On November 6, 1918, all three Republican candidates, including Riley, swept their elections to represent St. Louis' Fourth District in Missouri's House of Representatives.

History had been made: Riley was Missouri's first Black elected lawmaker. The Kansas City Times noted "the Missouri legislature this winter will have its first negro member," while the St. Joseph Gazette described Riley as "the first of his race ever elected to the state legislature."

But while the news of Riley's win traveled fast, the celebrations would be short-lived. An election controversy was brewing.

Unmaking history

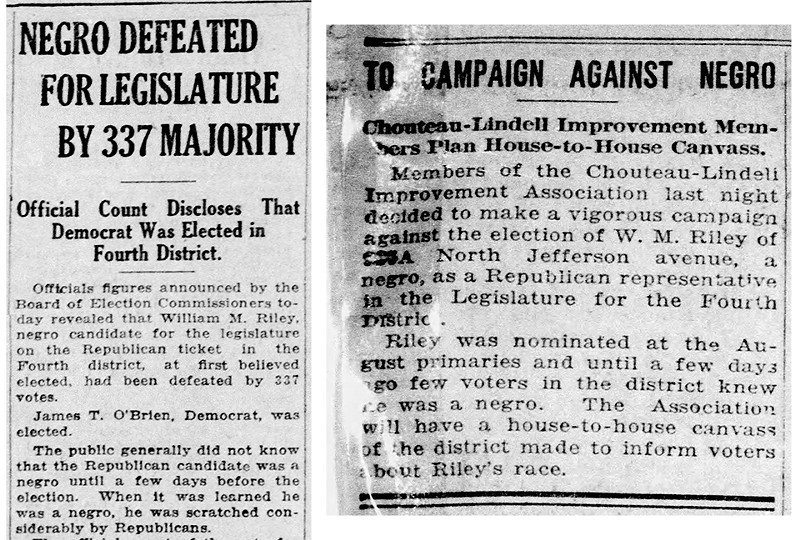

Less than a week after the first reports of Riley's victory, the November 13, 1918, headline from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch delivered a dramatic update: Although "unofficial returns had seemed to indicate his election," the paper reported a stunning reversal from the city's Board of Election, which had found that Riley was 337 votes short of the next highest vote getter, James T. O'Brien, a Democrat.

News of the electoral undoing traveled, but unevenly.

"The reporting on it was very confused for months after the fact," Elwood says. He adds that he found accounts of Riley winning his seat as late as three months after the election. But it's not clear what happened to the original count so breathlessly reported in numerous papers, and, as a historian and researcher, Elwood cautions that these are questions he can't answer.

"The reporting on this is a little bit contradictory," he admits. "Multiple outlets did report his victory as the official count, but you don't see a lot of concrete numbers that come with those reports."

Elections were not quick affairs in 1918, Elwood says. Early reports were often suspect.

"But," he continues, "it is significant how widely it was understood that Dr. Riley had won. You have a situation where the Board of Election Commission is mostly silent in the days immediately following the election until a week later, in which they announce the official results. And then, there is a great deal of conjecture about what happened. Was he so completely defeated within the midst of what was, throughout St. Louis, a Republican landslide? Was there something untoward? There's no concrete evidence that there was."

What there is evidence of, however, is a hastily organized coalition of St. Louis racists who united in their mission just days before the November election. The adherents had all come to the same startling discovery: William M. Riley was Black.

Apparently, this came as a shock. Although Riley was a known businessman and had been featured in the earlier Argus coverage that directly mentioned his race, a group known as the Chouteau-Lindell Improvement Association spent the final days before the election in an effort to manufacture the controversy as a bona fide election crisis.

The association seemed to benefit from newspapers' willingness to restate their claims uncritically: One week before Election Day, on October 31, 1918, the Post-Dispatch reported that Riley's race "was not known to most of the voters in the district."

The Post-Dispatch story doesn't exactly fact-check this assertion, though its coverage does include denials from local Republican leaders distancing themselves from Riley, and "deny[ing] responsibility for putting a negro on the ticket."

It's also notable that the Post-Dispatch coverage of the controversy included a description of Riley's appearance, suggesting that his detractors made it an issue: Riley's skin was said to be "white, except for the innumerable freckles, and his hair is straight" — but the article also acknowledged that Riley had "the unmistakable facial characteristics of his race, which he makes no effort to conceal."

This claim — that the white voters of District Four did not know that Riley was Black — would be repeated as fact in several ensuing accounts of the election. But the attention also gave Riley a chance to speak for himself: In a handful of interviews that represent some of the only direct quotes from the candidate himself, Riley denied that he had won nomination through deceit. He pointed out that his photo had been published before the primary, and that the white residents of the district knew him well.

In an interview with the St. Louis Star and Times, Riley responded forcefully to the actions of the Chouteau-Lindell Improvement Association, which the previous night resolved to canvass house to house in the district "to inform voters about Riley's race."

At a time when the world was at war, Riley argued for perspective: "Members of my race are fighting in France to make the world safe for the white man as well as for the negro," he said. "We ought to be treated like citizens and we are not going to be intimidated."

A missed opportunity

Riley was just one figure in St. Louis' burgeoning movements of Black political power. Yet, unlike Walthall Moore — whose 1920 election in St. Louis cemented his place, officially, as the first African American in the Missouri House — or attorney Homer G. Phillips — whose name became synonymous with the hospital he founded that trained generations of Black doctors and nurses — Riley's story lay dormant for decades, his legacy buried in newspaper archives and waiting to be rediscovered.

But where did he go after the 1918 election?

Through census records, Elwood found Riley's last listed St. Louis residence in 1922. By 1930, the census entry for a "Wm. Riley" — with the same date and birthdate — shows up in Baltimore, listed as a salesman.

"I do believe he left St. Louis," Elwood says. "I think it made it difficult to center ongoing advocacy around his election loss without him there to be part of it."

In fact, Riley had lived just three years in St. Louis before his election, and, as a transplant who appears to have departed not long after, Elwood says it is unlikely that he left behind any local living descendants.

As for Riley's disappearance from the press and history books, Elwood has several theories. One explanation is that Riley's ouster was bad political optics — particularly at a time when both political parties struggled to retain Black voters.

"It seems likely that Republican-affiliated papers would rather avoid mentioning their failure around that election," Elwood suggests. "The Democratic papers would likely wish to forget their attempts at voter suppression."

Indeed, Riley's election featured a familiar refrain of conspiracy theories around the supposed fraudulent importing of Black voters: As recounted in historian James Neal Primm's sweeping St. Louis history Lion of the Valley, proponents of the 1916 ballot initiative to legalize housing segregation spread rumors that Black residents of Memphis were being driven to voter registration in limousines "by the thousands."

The pattern repeated in 1918 with Riley; in its campaign against the optometrist, the Chouteau-Lindell Improvement Association told an Oklahoma newspaper that the supposed Republican scheme to elect Riley was tied to heavy voter registration in the Black community "which has been found to be fraudulent."

But Elwood says he's found no other reports of confirmed fraud during the 1918 election in local sources. Equally baseless, he says, were the reported claims that Black voter registrations for the 1918 election were traced to vacant lots, insane asylums and names "taken from tombstones in negro cemeteries."

Riley himself appeared to be aware of the attempts to undermine the vote: In pre-election coverage in the St. Louis Star and Times, Riley told a reporter that Black voters in his district "are being carefully instructed how to proceed on election day to forestall any fraudulent attempts to deprive them of their vote."

Whether Riley truly lost or was the victim of retroactive meddling, it's clear to Elwood that Black voters took note of the strategies being deployed to keep their candidate from the halls of power. Through the next decades, it became increasingly common to accuse Black voters of being "led to the polls" or of being brought across state lines to vote illegally.

Similar accusations were levied two years later when Walthall Moore made history by entering the Missouri legislature as a state representative in 1920. One newspaper, based in Caruthersville, made no secret of its hardline racism by lamenting in a story that "the 1920 election was stolen by illegal [n-word] votes." Another report in the paper noted Moore had won his 1920 election by a heavy margin, making it a "hopeless undertaking" to reverse. The report included another notable observation: It described how, "four years ago," a Black candidate was elected to the Missouri legislature "but was counted out, his margin being but small."

It was this last reference, a hint at what had transpired behind the scenes of Riley's 1918 election, that caught Elwood's attention. What seemed at first like an offhand detail motivated him to scour newspaper archives for the full story of how a Black lawmaker had been "counted out" of an election because of his margin of victory.

Riley's election showed how a dedicated group of racists could successfully overturn a Black victory. Two years later, with Moore's victory, Elwood notes that "it cemented a strategy of calling into question the legitimacy of elections that the white supremacist establishment opposed. If they did not like the results, they would preemptively claim that the results would be fraudulent. And those claims always fell along racial lines."

Riley's ouster — from politics, St. Louis and history — should stand as an important moment in the history of St. Louis and Missouri. In 2022, Missouri has 25 elected Black lawmakers in the state House and Senate, the largest number ever in the history of the Missouri General Assembly.

"It has taken a very long time to get to this point," Elwood says. Today, he calls Riley's election a "missed opportunity" for expanding enfranchisement for Missouri voters of all races.

"It was because of machine politics, because of the corruption that existed at the time, because of a more entrenched racism within both of the parties throughout the 20th century," he observes. "It's hard to say what might have been, but I do think that it would have been significantly important to have seen a Black legislator in our state — even two years earlier than we did."

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]