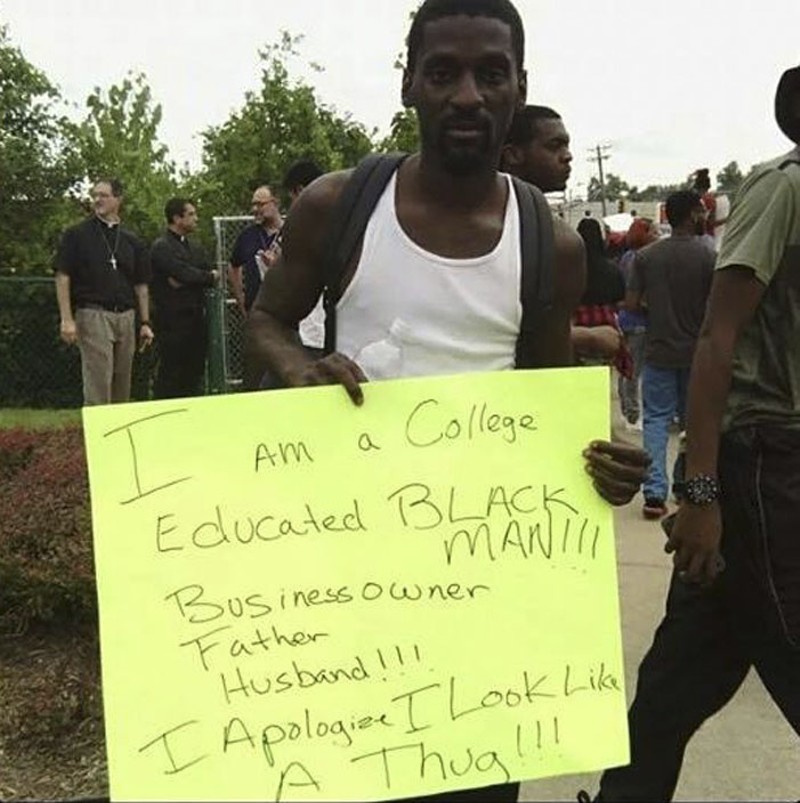

Bruce Franks Jr. knows he fits the description.

Black male. Age 30. Face tattoos and heavy eyelids. Wears a hoodie, drops St. Louis slang and even once caught a stray bullet. Franks is a battle rapper — stage name "Ooops" — who soldiered up on the frontlines of the Ferguson protests. When cops see him, he says, they see a thug — at least, the cops he isn't friends with.

But he is friendly with some cops. City police chief Sam Dotson texts him. City circuit attorney Jennifer Joyce tweets at him. Franks is not only a college-educated business owner, husband and father of five, but he's also an anti-violence activist, one who's trying to bridge the gap between the protesters and the protested. Which isn't easy.

Franks founded his organization, 28 to Life, in March. He's still waiting for the IRS to recognize it as a nonprofit. His primary mission, however, is clear: He wants to save black lives. All of them. He's well aware of the city's latest murder stats: Of the 133 total homicide victims in St. Louis from January 1 through August 25, 94 percent were black, and more than two-thirds of those were under the age of 30. Lately he's been seeking out that demographic in parts of south city, trying to hook them up with jobs and turn a few into activist-leaders.

At the same time, Franks believes that fatal police shootings of black residents, while far fewer in number, are an outrage — first because they're avoidable in many cases, and secondly because they devastate the community's trust in the system, without which the other murders won't get solved. So to tackle that problem, he has been working the halls of power.

Once a harsh critic of law enforcement, Franks has become a volunteer consultant who huddles frequently with the circuit attorney, police chiefs, police academy candidates, St. Louis City Hall leaders, and even the Department of Justice. He's been influencing public-safety policy at the highest levels — and doing it mostly behind the scenes.

"I got to know him and realized right away that when this person calls, I need to answer the phone," says St. Louis County police chief Jon Belmar. "He has no problem telling you when you've messed up, but he has the ability to listen and work things out. He's invested in this, and for the right reasons. I can't tell you how valuable that is."

Franks is not the only protester to move into policy work.

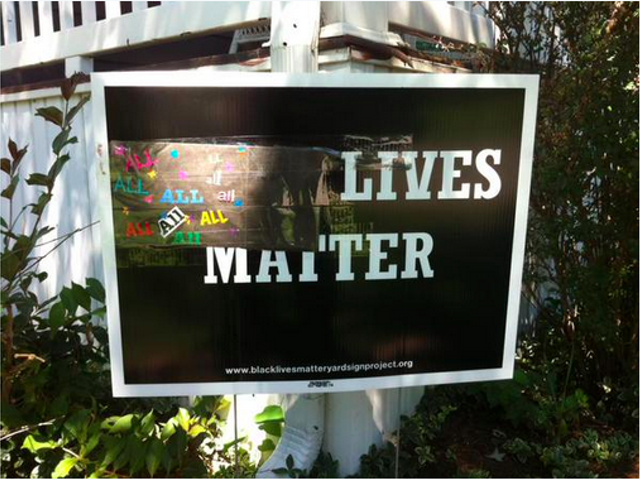

It's now been thirteen months since officer Darren Wilson fatally shot unarmed teenager Mike Brown in Ferguson, sparking the hashtag "Black Lives Matter" and nationwide demonstrations against police use of deadly force. Until recently, that movement took flak for being heavy on outrage but short on demands. Then, last month, several prominent activists launched Campaign Zero — a set of proposals ranging from officer body cams and de-escalation training to strong civilian oversight boards.

St. Louis native Johnetta Elzie, a member of the planning team and known on Twitter as @nettaaaaaaaa, says that Campaign Zero plans to win those changes by working with local, state or federal legislators. But directly with cops and prosecutors? Not interested, she says.

"I don't believe in them," says Elzie. "I'm all about going above them." Asked about Franks' efforts compared to hers, she says, "There's nothing wrong with doing both. We all need to do everything we can."

Franks' willingness to parley with law enforcers sets him apart in more ways than one. Some in St. Louis' protest base now consider him a traitor or spy, he says. It's expressed obliquely, whether through offhand comments (such as "Ooops is with the ops," which he recently overheard) or just a greeting that feels cold and short.

That kind of reaction doesn't surprise DeRay Mckesson, another member of Campaign Zero's planning team.

"I get why people are skeptical," says Mckesson, who moved to St. Louis during the Ferguson unrest and has since become a national voice for Black Lives Matter. "He doesn't play a role that I would play. But he has clear reasons as to why he engages this way, and he has integrity."

Even Franks himself sometimes marvels at his new role.

After nightfall on August 10 — one day after the anniversary of Mike Brown's death — protesters gather on the west side of West Florissant Avenue in Ferguson. They shout "We shut shit down!" at the cops bunched across the street. A helicopter thwumps overhead. Franks yawns.

"I can't wait for this to be over," he says, mellow and slow, as usual. "Not the protests. I'll always be a protester. I mean, the need to protest." He just wants justice to be done, he says, so they can all go home.

A few minutes later, he studies his cell phone, then shakes this head.

"Man, that's crazy," he says. A U.S. Department of Justice official has just texted him the words, "Be safe."

"A year ago," he says, "I didn't even know what the justice department was."

The story of Franks' youth is inked onto his skin.

The "Gibson" tattoo on his right hand refers to the street where he grew up in the Forest Park Southeast neighborhood. There, on June 7, 1991, Franks' older brother, nine-year-old Christopher Harris, died from a gunshot wound to the back. Witnesses said a crack dealer had used him as a human shield against an attack from a rival. Franks was only six.

The boy's death caused a public outcry, which led to a city-sponsored gun buyback program that eventually brought in some 7,500 firearms. Some of those guns were later melted into a statue of Harris that still stands in front of Cardinal Glennon Children's Hospital.

A second family tragedy struck that same year, in the same neighborhood: In December 1991, Franks' cousin, Roger Fields, a city sheriff's deputy, was ambushed outside a bar on Manchester Road and killed.

To escape all the violence, Franks' mother moved her children to the Cochran Gardens housing complex downtown. But it turned out to be worse.

Franks remembers peering out their apartment window late one night and watching a man on his knees plead for his life to an armed robber, who shot the man anyway. (Thanks to neighbor involvement, Franks says, the perpetrator was later caught.)

It was around this time Franks first met a policeman. Rodney Wilkerson, a city officer, was a family friend. One day, he gave the boy a globe as a gift.

"Kids from the 'hood don't play with globes," Franks observes. Wilkerson pointed toward St. Louis on the map, which was so small, it wasn't even marked. "He told me, 'There's a much bigger world outside what you living in.'"

Franks soon learned that lesson first-hand. His parents, separated by that time, both moved to south city, but Franks spent his days in the southwest St. Louis County suburbs as a voluntary desegregation student in the Lindbergh School District. His classmates were mostly white.

"It was a culture I wasn't used to," he says. "But we got to grow together. To this day, they're some of my best friends."

Upon graduating from Lindbergh High School in 2002, Franks enrolled at St. Louis Community College's Florissant Valley campus and ran track (the triple jump and long jump were his specialties). But at the end of 2004, a gun ended his athletic career.

Franks says he had just finished playing basketball in the Walnut Park East neighborhood when a shootout erupted close by. He took a stray bullet in his right knee.

After the injury, he tattooed the name of his daughter Taj, who had just been born, on both his right temple and his neck.

"I didn't know how long I was gonna live to be her father," he says.

Even that episode didn't compare to the dual tragedy that befell him two years later, which inspired the tattoos streaming down from his eyes.

Just before 8 a.m. on October 20, 2006, Franks got into a heated cell-phone argument with his then-girlfriend, Juanita "Buggy" Betts. She was driving north on U.S. 67 near Jamestown Mall, when suddenly, the call cut out. Franks assumed she had hung up on him.

Later that afternoon, he discovered the truth: Betts had crossed the center line and T-boned another car carrying a married couple (both Hurricane Katrina refugees, it turned out). All three died in the collision.

As if that weren't enough, seven days later, Franks' grandmother, Bonnie Jeanne Harris, who had helped raise him, succumbed to cancer.

"The double impact — I still haven't gotten over it," he says. The tattoos under his eyes, he says, are for "the tears I don't have to cry anymore."

Franks threw himself into a new hobby: rapping. When not toiling in the restaurant industry as cook, server or bartender, he wrote verses and entered open-mic nights. With influences ranging from Eminem and Stevie Wonder to Rod Stewart, he adopted the stage name "Ooops," which he tattooed on both his face and neck. He eventually recorded with Wacka Flocka Flame and the local rapper Huey, who is his first cousin.

His lyrics during that period contained more swagger than social commentary. In "Stand Up," a single released in 2010, he bragged about his native St. Louis as "the real murder capital":

It's goin' down hurr,

might not wanna come 'round hurr,

you can get lost and not found hurr,

trip and we let off some rounds hurr

But he soon opted for a more domestic vibe. In July 2010, he met Dana Kelly, an insurance saleswoman and poet. They went on their first date the next month and have been inseparable ever since. Perhaps it was fate: They were both born on September 22. They chose that day in 2012 to get married.

By the summer of 2014, they were living in a well-kept, two-story brick house in Benton Park West. Between them, they owned and operated an Allstate insurance office a block away, in addition to a seasonal Kwik Tax office and Kwik Print shop on Cherokee Street. They also had a son named King.

On King's first birthday, Franks posted a video online of the happy baby wiggling his arms. It was August 9, 2014.

That afternoon, Franks heard about Mike Brown.

Paul Muhammad first saw Bruce Franks as just another hothead Ferguson protester.

"At that point," Muhammad says, "he wanted to turn up and tear shit up."

Franks had driven up to Ferguson the morning after Brown's death without knowing why. He wasn't into politics.

That changed after a few nights of tear gas. "THERE IS A WAR BEING WAGED UPON US," he wrote on Facebook on August 29. "IF THERE IS NO JUSTICE, I WILL SHOW YOU EXACTLY WHAT NO PEACE LOOKS LIKE."

A regular on the frontlines, Franks ran into Muhammad, who had co-founded the Ferguson Peacekeepers, an informal clique that stood as a "buffer of love" between cops and protesters so the latter could vent without putting themselves or others at risk. Noting Muhammad's poise in tense moments, Franks asked to join.

"If you're gonna put on this hoodie," Muhammad told him, "you have to be a de-escalator and watch out for agitators. We're with the movement, but if they're throwing rocks and bottles, you need to step to those people." Franks agreed.

Yet even the Peacekeepers couldn't always keep the peace.

At about 11:15 p.m. on Christmas Eve, a police officer fatally shot eighteen-year-old Antonio Martin at a Mobil gas station in suburban Berkeley. Surveillance footage would later reveal that Martin raised a gun at the officer. But the hundreds of people who quickly converged didn't know that yet. Things got ugly fast.

The Peacekeepers arrived and tried to soothe tensions, but when police started to arrest one of them, both Muhammad and Franks intervened. In the melee, police brought them to the pavement, pepper sprayed and arrested them.

Franks had bloody cuts on his face and leg. He was jailed for several hours on charges of resisting arrest, interfering with arrest and assault on a law-enforcement officer.

Four days later, he again wrote on Facebook: "ITSTIMEWEFIGHTBACK!!!"

One of the darkest hours of Tom Jackson's tenure as Ferguson police chief, he says, actually occurred in Boston — and Bruce Franks was part of it.

The chief was seated inside Harvard Law School alongside seven other panelists on January 17. Their goal that afternoon was to discuss how to heal the wounds festering in St. Louis since the Ferguson unrest.

Jackson is not a smooth orator under pressure. He jumbles words; his voice quivers. That was evident at his first press conference after Brown's shooting back in August 2014, when he looked totally overwhelmed by the national news cameras. During an unscripted apology to protesters weeks later, he had even publicly called Brown's death "a fucking tragedy," without realizing he'd dropped the F-bomb until a reporter pointed it out the next day.

At the Harvard panel, Jackson hoped to calmly dispel some myths about his handling of crisis. He also wanted to flesh out his ideas for overhauling Ferguson's police force — a project he said he truly believed in.

"Otherwise, why would I be here," he said into the microphone, "knowing some of the response I'm going to get?"

The response did prove hostile, but to his surprise, it came from his fellow panelists.

"When will you offer your resignation?" asked Justin Hansford, a Saint Louis University law professor, directing the question at both Jackson and Ferguson mayor James Knowles III, one seat over. As the chief replied, the Harvard Law student on his left, Derecka Purnell, physically turned her back on him.

Paul Muhammad, also on the panel, took his turn sparring with Jackson, at which point former Missouri GOP gubernatorial candidate Dave Spence, sitting in between, gave up listening and played with his cell phone.

But nobody exploded like Franks.

At first, the wiry five-foot-five Franks just seethed at the far end of the table. Then he rose and glided toward Jackson, spitting bars about how a police gun gets used on a black person: "'Round my way, one flash from that tool get rid of that body, leaving only recollections and memories."

Jackson recognized his face. "I knew him from some 'home events,'" he says.

Franks finished his rap and sat back down. A half-hour later, he erupted again after Jackson claimed that police only deployed tear gas on protesters after gunshots.

"You can't tell me we was tear gassed because of no gunshots," he railed, jabbing his finger. "I was tear gassed because I was standing there making it inconvenient for you motherfuckers!"

Once the event ended, Harvard campus security guards ushered Jackson and Knowles separately out of the building.

Still, the panelists reconvened for dinner at Legal Sea Foods, a restaurant in nearby Harvard Square. Andre Norman, the ex-con and motivational speaker who had organized and moderated the panel, noticed Franks was still upset at the chief. He pulled the 30-year-old aside.

"I told him, 'If you want to do business on behalf of your people, you're going to have to talk to that man,'" Norman recalls.

How are you going to change policy, he asked Franks, if you won't talk to the policymakers? Screaming at people only makes them shut down.

Franks walked over to Jackson's table and took a chair.

"He had his hands folded in front of him with his head down," Jackson says. "Then he quietly said, 'I'm not sorry for what I said. But I'm sorry for the way I said it.' So I said, 'Let's just talk.'" And they did. For hours. Until the restaurant closed.

Back in St. Louis, Franks says, Jackson called him within 48 hours to ask for his advice on various initiatives, including diversity training for officers, minority recruitment at Ferguson's high school and a cop-community brunch.

Ultimately, Jackson lost his job. Six weeks later, the U.S. Department of Justice released a blistering report. It concluded that Jackson had presided over a police squad that disproportionately used force against black residents and targeted them for petty offenses to fund city operations.

The DOJ report revealed Jackson's role in the so-called "taxation by citation" practices. It did not, however, clarify the extent of his complicity in the targeting of African Americans. Maybe the chief should have been aware of it and wasn't. Or maybe he was indeed aware, then had a change of heart. Franks doesn't dwell on it. He says he saw in Jackson a genuine desire to right the wrongs committed by the department. To this day, he considers Jackson "a good guy."

The Ferguson police under Jackson would seem like a prime example of "institutional racism" or "white privilege," but Franks almost never uses those words. He doesn't deny their existence; he simply prefers to speak in terms of specific individuals who either help or hurt his cause.

Those who share his goal of saving black lives, he says, are "my people" — however they may look.

When it comes to solutions, he says, "It ain't about black and white. It's about right and wrong."

Mike Brown's death only seized Bruce Franks' attention. What really launched him on a full-time crusade was the killing of VonDerrit Myers.

At about 7 p.m. on October 8, city officer Jason Flanery was clad in his police uniform working as a private security guard in the Shaw neighborhood. As he approached a group of young men, one took off running. Flanery chased him, but couldn't catch him.

Minutes later, Flanery again came upon group of young men. He thought he recognized the runner among them. It turned out to be someone different — eighteen-year-old Vonderrit Myers, who was supposed to be on house arrest (he was wearing a court-ordered ankle bracelet as a condition of bond in a gun case).

Myers fled, climbing up a front-yard hill and ducking into an alley. Flanery pursued him. He would later say that Myers produced a silver handgun and fired down at him, so the officer returned fire. Around twenty gunshots later, Myers lay dead in the gangway, a gun by his side.

Surveillance video from a nearby deli showed that Myers had shopped there right before the encounter. So a rumor quickly spread: Myers never had a gun in his hand; he only had a sandwich.

The circuit attorney launched an independent review. Prosecutors sifted through physical evidence. They tried to re-interview all police witnesses and find new ones, though later reported that "a number of witnesses declined."

Attorneys for the Myers family told local news outlets they'd heard Myers was "begging for his life," in the alley, only to be executed by Flanery. So investigators asked the lawyers several times to produce those witnesses. They never did.

On May 18, Circuit Attorney Jennifer Joyce announced she would file no charges against the officer.

In a 51-page report, her team wrote that the physical evidence alone proved that Myers' gun fired at the officer from the gangway. Several witnesses saw or heard those shots. Furthermore, the team wrote, "no witness claims to have seen [Flanery] alter evidence in any way," not even Myers' acquaintances, who were standing nearby. Therefore, the officer's justification for deadly use of force would be insurmountable in court. No prosecutor could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he had committed a crime.

"It is a tragedy that a life was lost in this incident," the team concluded.

Two days later, about 40 people displeased with Joyce's decision showed up to her home in Holly Hills just after 9 p.m. They chanted, "No justice, no sleep!" Police arrested six of them for peace disturbance, resisting arrest and trespassing.

"It was very disheartening to see how things were rolling out," says Joyce. "We'd worked so hard on that report. I found that a lot of the protesters didn't read it."

She agreed to meet with them in small groups and let them record it, she says, but it never happened. "They wanted a town-hall meeting," she said, "not a conversation where you could talk about these things and reach some understanding."

Then Bruce Franks came to see her. He carried a copy of the Myers report.

"That thing looked like a law-school textbook the night before a final exam," she recalls. "It was dog-eared, it was highlighted, it had sticky notes all over it. And he had very thoughtful questions."

The Myers case haunted Franks, he says, because it happened three miles from his house. This is right in my zone now, he thought. Reflexively skeptical of all police narratives, he did his own investigation.

That day in Joyce's office, he spoke to her for nearly two hours.

"I didn't like her decision," he says. "But given what she got from witnesses, I understood how she came to it."

Then he told her that the Myers family deserved an explanation from her, in person. Joyce replied that she had already invited them several times, to no avail. So Franks, who knew the family personally, arranged for them to meet on June 15.

However, he says, the grieving parents bowed out at the last minute. "It wasn't the right time," he says. "They lost their only child."

"I can't imagine the heartache they feel losing their son and not having charges brought," Joyce says. "I'm not going to push it. Hopefully at some point they'll feel like they want to come talk to me."

After that meeting with Joyce, Franks felt like he could do business with her. He recently brought into her office a witness to the fatal police shooting of Kajieme Powell that occurred on August 19, 2014 — another case in which Franks is convinced an officer unnecessarily ended a black life. Franks believes that Joyce, supplied with the proper evidence, will do the right thing.

He's even given her a nickname: "J.J."

"My husband thinks it's pretty funny," she says. "I didn't even know battle rap was a thing. So then I'm at home on a Saturday morning at the breakfast table looking at YouTube battle-rap videos, and my husband's like, 'Who are you?'"

Joyce's staff is now seeking Franks' advice on a major project: the call-in program. The idea, which has shown some success in Kansas City, is to identify ex-offenders fresh off probation or parole who risk falling back into violence. They're invited to meet with a team of law enforcers, victims, other ex-cons and service providers, who deliver a delicate balance of carrot and stick: We're watching you, but we also want to help you stay straight.

On August 7, Rachel Smith, an assistant circuit attorney, called Franks into a fourth-floor conference room at the state courthouse downtown.

"We need to get the right message to the right people," she tells him. "And we want the message to be about promises, not threats."

Three gangs generate most of the gunfire in the city, she explains. The plan is to "call in" about 25 mid-level leaders from those rival groups who are newly back on the streets. They'll have to pass through metal detectors.

"My concern," says Franks, reclining in his swivel chair, "is when you get these guys to come out, you wanna be compassionate. They've had that iron fist for so long, they're going to put up a block."

Smith asks Franks if he'd like to address them.

"I'm with it," he says. "Just put me in front of 'em. Who you got from the police?"

Smith lists two high-ranking officials.

"No," he says. "I know how these young guys are. We see gray hair, it's done." He suggests a younger black female sergeant he knows. "When she talk, people listen."

As the meeting wraps up, Smith seems anxious. "I know that we as law enforcers need to do things differently," she says. "The question is how to do it."

After the meeting, Franks steps into the elevator, lost in thought. "That Rachel Smith," he says. "She give a fuck, for real. It's not fabricated. Just like J.J."

Franks named his new grassroots organization, 28 to Life, after the statistic-turned-meme that a black person is killed by a cop every 28 hours. That figure, pulled from a report by the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, went viral in the wake of Ferguson. It's not true.

The statistic has been debunked by PolitiFact and the Washington Post. But Franks hasn't given it a second thought — which is indicative of how fast he's been moving. He seems to experiment with a new initiative every week, just to see what sticks.

It also reflects how singularly focused he is on his programming, at the expense of branding — not to mention fundraising.

"He's not very good at asking for money," says Alderwoman Cara Spencer of the 20th Ward, where Franks is based. "As soon as he gets that 501(c)3 status, we can maybe get that rolling." For now, Franks says, he has only received a few hundred dollars in donations. He and his team work as volunteers.

The group's logo shows the number 28 inside the Superman diamond. He chose that shape, he says, because he's "in the business of making superheroes." That's partly a reference to the several teen summits he has held on Cherokee Street, wherein local kids meet law enforcers — employees of the FBI, U.S. Attorney's office, Circuit Attorney's office and city police have all attended. With their input, the teens hash out the problems on their blocks and craft plans to fix them.

But "superhero" is also a reference to what he thinks every cop should be: a nimble problem-solver who not only locks up villains, but can also disarm a threatening suspect through verbal or tactical jujitsu, without killing him. He recognizes that in some cases, deadly force is necessary and legal. But it should be rarer than it is.

In addition, Franks believes, a "superhero" cop is also incorruptible. That explains his reaction to a radio segment he heard on April 5, when Heather Taylor, a city police sergeant, called into The Demetrious Johnson Show on Hot 104.1 FM.

Taylor had just been elected president of the Ethical Society of Police (ESOP), which has historically been a black officers' association. Displaying no fear of rankling the top brass, Taylor knocked them for failing to promote black officers. She also bemoaned the new distribution of manpower that favors downtown at the expense of the largely poor and black north side.

Yet when it came to ethical crime-fighting, racial solidarity took a back seat.

"If white officers are doing wrong, they need to go," she said. "If black officers are doing wrong, they need to go too, because it's all about the community."

Hearing those remarks, Franks immediately texted his police contacts to find her.

When they connected, she told him that the previous November, the mayor's office had agreed to set aside $50,000 in public-safety funds to partner with ESOP on a minority-recruitment program. The course's aim was to bolster minority applicants to the police academy by getting them up to speed on computer literacy, professional etiquette, use-of-force protocol, and strategies for acing the required exams.

Taylor invited Franks to attend and give the pre-cadets a citizen's perspective.

"When he started class with us in March, he was very angry," says 29-year-old applicant Rosa Rojas. "His intention was to bash cops."

But by debating with instructors sergeant Bill Clinton and detective Keaton Strong over use-of-force videos, she says, Franks seemed to find some common ground.

"He really just wants to stop African Americans from being killed," she says.

Common ground doesn't always come so easily. Progress can become mired in politics.

Franks recently hatched an idea for a gun-buyback program. He wanted it to include a resource fair, a job fair and amnesty for certain nonviolent offenses in exchange for community service.

So he broached the topic with city police chief Sam Dotson, who supports the buyback concept. Franks found another receptive audience in board of aldermen president Lewis Reed, who had already passed a resolution authorizing buybacks in January 2014.

But Franks didn't realize how complex city hall alliances could be. The media got wind of the plan and publicized it before Franks, Dotson and Reed could hash out who else would be involved and how exactly to fund it. A flurry of phone calls and miscommunications ensued, and Franks feared his coalition was unraveling.

While he says the project is now back on track, the lesson was a frustrating one.

"I don't give a fuck about these politics, man," he said at the time. "I want everybody to be involved."

Last month, two very different deaths made headlines in St. Louis.

On August 18, someone fired a gun into a Ferguson home, killing nine-year-old Jamyla Bolden as she did her homework. Then, the very next morning, city police serving a search warrant in the Fountain Park neighborhood shot and killed eighteen-year-old Mansur Ball-Bey, claiming he pointed a gun at them.

The latter triggered a swift and angry demonstration, followed by tear gas from police, arson and looting. No such drama accompanied the fourth-grader's death. The conservative website Breitbart.com crowed, "Black Lives Matter Couldn't Seem to Care Less About Jamyla Bolden."

But that wasn't exactly true. Hundreds converged at a candlelight vigil for Bolden on August 20, including activists such as Kayla Reed of the Organization for Black Struggle. She says that activists may have initially coalesced around stopping police violence, but the movement has grown.

"Black Lives Matter encompasses black life in every field," she says, from the "community violence" that took Bolden's life to education to housing. "There's enough work for everybody," she says.

Franks does that work — he has become just as invested in stopping community violence as police shootings.

The police department's 3rd District, which he calls home, overlaps with some of south city's most violent blocks. In July, after a spate of shootings involving young men, 3rd District captain Mary Warnecke grew concerned about retaliation. She asked Franks if he could help resolve the beef. So he investigated. He managed to get one of the young men a job through a family member's business.

It didn't last, but Franks decided to scale up. He began recruiting local youths for a jobs-training program through St. Louis City Hall. All told, he has sent 30 young people to the program in about a month.

"These last few weeks I've had fewer shootings," says Warnecke. She hesitates to credit the whole reduction to Franks, but adds that sometimes all it takes for someone to go straight is the right messenger. "I like to think we're on the right path."

That kind of cooperation doesn't always sit well with people on the street. On the day Mansur Ball-Bey was shot by police, a protester at the site of the shooting is quick to dismiss Franks to a reporter.

"Man, I don't know where Ooops at," he says. "He up with the police now."

And later, that assertion proves partly true. At 5:30 p.m., Franks is slouched on the hood of his car in the parking lot of the Nathaniel J. "Nat" Rivers State Office Building on Delmar Boulevard. He has arrived early for the police's minority-recruitment class. A Fox2Now helicopter loops like a vulture about six blocks to the north over Page Boulevard and Walton Avenue, where demonstrators are growing restless.

In an earlier conversation, Franks noted the value of violent protest, citing Martin Luther King's notion that rioting is the language of the unheard. "When they're out here burning and breaking shit," he said, "I don't condone it, but I don't condemn it. I'm a business owner. Do I want my business burned down? No. But if these young adults hadn't burned shit down, then the world wouldn't know about Ferguson."

But this evening, he just wants to vent at his critics in the movement.

"Y'all want to protest until the end of time. But if you can't ever sit down with the people you're protesting against, you ain't goin' toward any solution. The only way to know if what they're saying is bullshit is to actually listen to what they're saying."

The minority-recruitment class is about to begin. He slides off his car and trudges inside.

Within the next few hours, protesters in north St. Louis will hurl bottles at police. Police will respond with tear gas. All will make headlines.

Bruce Franks, meanwhile, will try to make superheroes.