On December 17, 1862, nearly 150 years ago (minus six months or so), General Ulysses S. Grant expelled the Jews from the Department of the Tennessee, the war zone under his command, which stretched from northern Mississippi to Cairo, Illinois, between the Mississippi and Tennessee rivers.

Within three weeks, President Lincoln had countermanded the order, known as General Orders No. 11, and the Jews were allowed to return to their homes. But the effects of the order lingered for several decades -- though not in the ways one might expect.

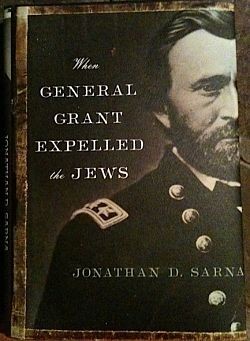

Jonathan D. Sarna, a historian and professor at Brandeis University, tells the story of General Orders No. 11 in his latest book, When General Grant Expelled the Jews. He'll be at the Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site at Grant's Farm (which Grant actually did farm, in the 1850s) tomorrow evening at 7 p.m. to discuss the book, but he took some time this morning to chat with Daily RFT by phone.

Daily RFT: Tell us a little bit about General Orders No. 11.

Sarna: I could tell you a lot about General Orders No. 11.

Just the good parts, then.

General Orders No. 11 is certainly the most anti-Semitic official government order in American history. On December 17, 1862, Ulysses S. Grant expelled Jews as a class from the area under his command, within 24 hours. It's the only time Jews as a class were expelled in the United States.

Why did he do it?

He wanted to put an end to smuggling. In a sense, he did what people often do. Some of the smugglers were Jewish. Therefore, he decided, all Jews must be smugglers. As a result of that, instead of expelling smugglers, he expelled Jews as a class.

Jews must have been easier to identify than smugglers.

Many Jews were immigrants. They had accents. They looked and dressed differently.

There's a cause, and there's an occasion. The cause is that smuggling was widespread. You can see it in [Grant's] papers for a year before he issued the order. The occasion is something else -- why he did it on December 17, especially since he had countermanded a similar order in Holly Springs [Mississippi]. Before the order, Grant's father had come to visit from Cincinnati with a family of Jewish merchants called the Macks. They cooked up a scheme to move cotton northward, and Grant's father would get 25 percent of the profit. When Grant realized his own father was engaged in smuggling, he immediately sat down and expelled the Jews. In a sense, he expelled the Jews instead of his father.

Did the Jews actually leave?

After Grant issued the order, Holly Springs was attacked and the telegraph lines went down. So the order spread very slowly. Many Jews did leave on boats to Cincinnati or Louisville, outside the war zone. And then when the order hits Paducah [Kentucky] ten days later, 30 Jewish families left, which sets in motion the events that led to the order being revoked by Lincoln [on January 4].

Did they go back after the order was revoked?

Cesar Kaskel, the main protagonist of my story, did go back to Paducah. But after the war, that area went into economic decline, and many Jews left. Kaskel went to New York and opened a clothing store. But the order was remembered within the Army, and many Jewish soldiers found their position was an awkward one, their peers and so on knowing they were Jewish and reacting negatively. Several resigned from the military.

And Grant -- he went from issuing this anti-Semitic order to becoming what you might call a philo-Semite.

That's the biggest surprise. Grant grew from the experience. In the wake of the 1868 election when the order became a major issue, Grant makes it clear that he's not that kind of person, that he judges people as individuals. He said, "I do not sustain that order." Jews took it as an apology. And as President, Grant is remarkable in demonstrating that.