One of the hardest hit federal prisons is located in Springfield, Missouri, at the BOP's Medical Center for Federal Prisoners, which houses some of the nation's most medically vulnerable inmates.

The extreme dangers they face were underscored in early February in a scathing opinion written by U.S. District Judge Ronnie L. White, of the Eastern District of Missouri, in St. Louis.

White slammed the BOP for its handling of the case of a diabetic inmate seeking compassionate release from the Springfield facility.

White noted in his order granting the prisoner's release that, at the time, seventeen MCFP inmates had already died there, while 384 inmates and 212 staff were listed as having recovered from COVID-19 infections.

"These numbers reflect a shocking outbreak of cases and deaths at an institution where the BOP places medically fragile inmates," White wrote.

To critics of prison medical care, White's blistering opinion is hardly surprising. Long before the pandemic started, America's prisons and jails generated voluminous complaints about tardy, substandard and even unethical inmate medical care, including well-documented cases of coerced human experimentation.

"They didn't get good medical care in good times," says Dragan, the public defender, whose clients are scattered in lockups across the Midwest. "They're getting really shitty medical care now because they don't want to take them out of the facility for any sort of medical care."

Exacerbating these issues is the fact that federal prison inmates often fail to report their symptoms to prison medical personnel for fear of making things even worse for themselves. Sick inmates are usually quarantined in their prisons' disciplinary housing, according to the ACLU's Morris.

"And people don't want to go there," she says. "They're very uncomfortable units. They are not getting close medical monitoring. They tend to be dirty. They tend not to have a lot of water access. And people are afraid to go in there."

All these factors taken together — the poor testing regimen, the lack of ventilation, the shortages of PPE, the crowding and lack of transparency — draw Dolovich, of UCLA Law, to one conclusion about the federal prison system.

"It's the most effective COVID transmission system we could come up with," she says.

So far, at least 240 inmates and four staff members have died from COVID-19 in America's federal prison system, according to COVID Prison Project data.

Nearly 50,000 federal inmates — about one-third the total federal inmate population — have tested positive, as well as nearly 6,500 staff, BOP data show.

Federal inmates make up a fraction of the total number of inmates locked up across the country in jails and prisons, and they can sometimes be obscured in the statistics. But the federal death toll is significant. If the BOP was a state system, it would rank second only to Texas, which has reported more deaths — 257 — but also has a larger prison population, totaling 163,000. Missouri's system has registered 48 deaths out of a population of 26,000, according to the prison project website.

The Tucson prison, where Howard died, recorded the third-highest number of positive COVID-19 cases compared to other federal prisons — 895 — surpassed only by the federal prisons at Fort Dix, New Jersey, with 2,014 cases, and Seagoville, Texas, with 1,240 cases, BOP data show.

As far as the deadliest federal prisons, USP Tucson is officially tied for second with two others that have recorded ten deaths each. The deadliest federal prison is the hospital for federal inmates in Springfield which documented eighteen deaths.

Medical records obtained by the RFT show that on the night of October 26, Howard was taken by ambulance from USP Tucson to the nearby Tucson Medical Center after experiencing shortness of breath and respiratory distress.

Howard spent several days at the medical center, where medical personnel inserted a tube in his stomach for nutrition.

"He wasn't there that long when a doctor called and asked if we wanted to have him removed from the ventilator," Pam Howard says.

"And I'm like, 'For what reason?'" she says. "I go, 'He still has brain activity.' And she said it's not up to her. It's up to the Bureau of Prisons, and the only way we could see him is [if] we chose the end-of-life option. Which I thought was unfair."

Howard was later transferred to Curahealth, a Tucson rehab center. A day later, he sustained a fall there and went back to the medical center, where he underwent a CT scan, which reported negative results.

An ambulance returned Howard to Curahealth, where, just after midnight on December 3, his heart rate dropped dramatically, according to a physician's notes.

"Patient's pulse was not palpable," wrote Dr. Bijay Sanjeev.

An ambulance took Howard to the St. Joseph's Hospital emergency room, where he was pronounced dead, according to his Pima County death certificate.

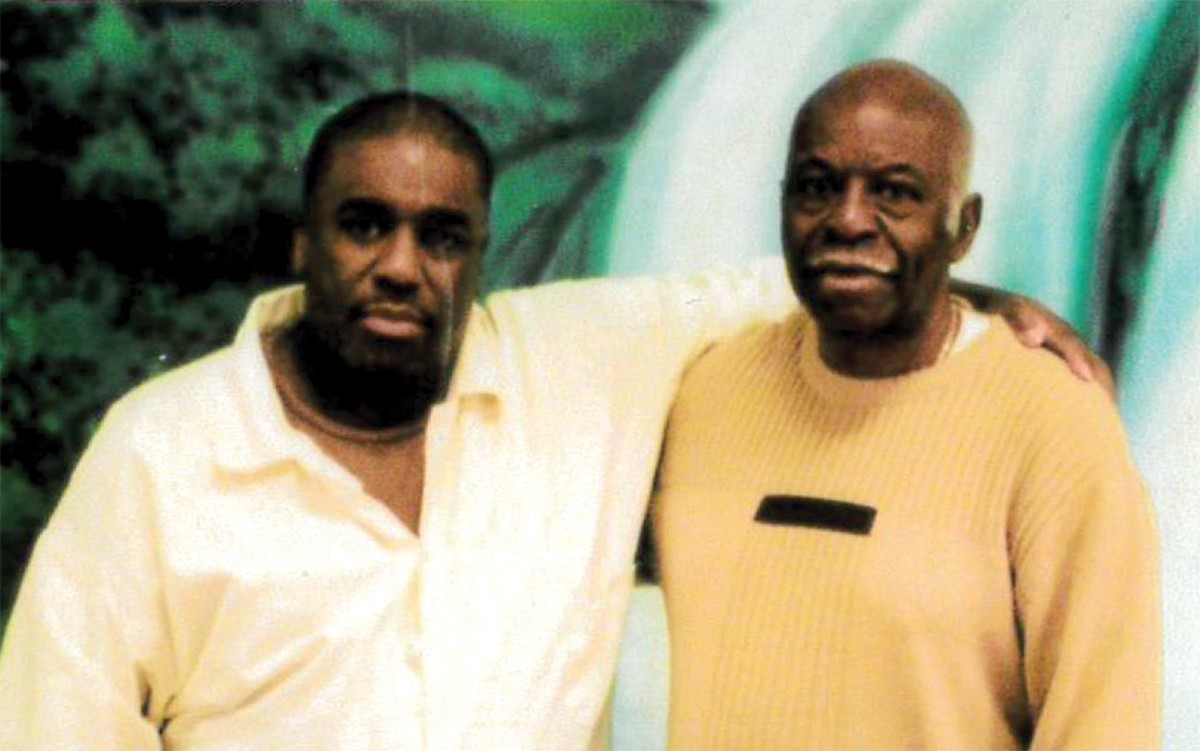

Derrick Howard died alone and cut off from his family, Dragan says.

"They never set up a phone call," Dragan says. "They never set up a Zoom visit ... [Howard's family] didn't get to be there for him. He didn't have any idea anyone in the world gave a shit about him."