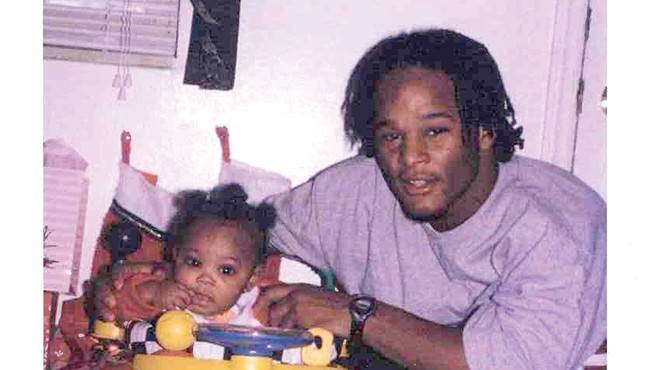

COURTESY PAMELA STANFIELD

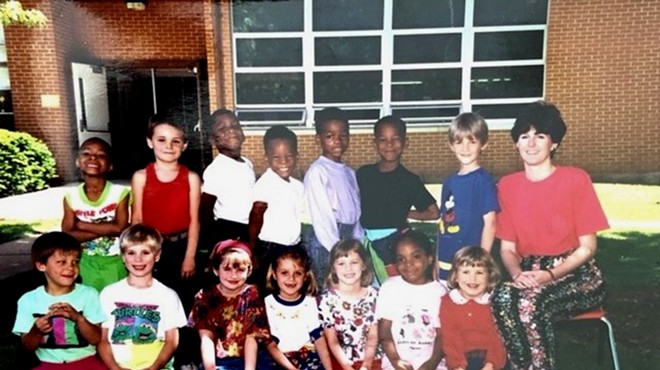

Khorry Ramey (left) and Kevin Johnson (center) and Johnson's elementary school principal Pamela Stanfield (right).

Editor’s Note: When he was 19, Kevin Johnson committed a heinous crime killing police office Sgt. William McEntee. After he was incarcerated, Pam Stanfield, Kevin Johnson’s former elementary school principal, maintained a relationship with him in prison. For his crime, Johnson was executed, and he asked Stanfield to bear witness. Stanfield was there with the head of Johnson’s legal team and Johnson’s brother and sister. Johnson’s daughter, Khorry Ramey, was not able to view the execution because she is only 19, and according to state law, one must be 21 to view an execution. Here Stanfield recounts her experience. Kevin Johnson’s funeral is today.

The letter from Richard Adams, the warden at the Eastern Reception Diagnostic and Correctional Center, said to report to the administration building at 5:00 p.m. for the 6:00 p.m. execution. I had been to the prison property earlier that day when Khorry, her 2 ½ month old son Kaius, and I visited Kevin for the last time. At that time, I was taken aback by what seemed to be swarms of guards in black camo pants and black vests everywhere. There were barrier gates on the property as well — nothing like the deserted prison I had seen a week before when I traveled from Potosi on November 22 after a prior visit with Kevin to make sure I knew where the prison was.

When I drove into the entry area at 4:45 p.m., a guard checked my ID against her typed list of approved witnesses and asked me to return 15 minutes later. I needed to find Khorry to give her the notebook and pen she had requested I bring her, so the guard directed me to the grassy area where supporters were gathering. Khorry wanted the people who were there supporting her dad to sign her notebook with their contact information so she could thank them.

After giving Khorry the notebook, I drove Kevin’s sister and brother back to the same entrance since they were also approved witnesses.

We walked through a closed connecting hallway with locked doors at both ends where we showed our IDs to a guard high up behind glass. Then we were escorted to a second building, and instead of going to the large room where Khorry and I had visited Kevin earlier, we entered a doorway on the left and found ourselves in a small waiting room.

A small table and three chairs were to our right where the prison employees sat. There were plastic chairs along the opposite wall together with a cooler that had water and soft drinks. On a table ahead of us were coffee, napkins, oatmeal raisin cookies, colored pencils, puzzle books, games of chess, checkers, and scrabble as well as magazines. Next to the employees was a TV set that at first appeared to be counting down minutes but then changed to a “no signal” screen. There was a sound machine that was on at a fairly high volume which sounded like rushing water.

In the waiting room, we sat on plastic chairs, quiet at first, but as the minutes passed, we talked among ourselves. The three prison employees sat quietly, one paging through a magazine. Kevin’s sister’s leg was in constant motion and Kevin’s brother was blowing his nose a lot, fighting a cold.

We were told by Shawn Nolan, the lawyer and lead attorney for Kevin’s legal team, that we were still waiting to hear the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court. Joe Luby, another one of the team lawyers was on the phone with the court waiting for the decision, and was to call Shawn as soon as he knew anything.

“I have bad news,” Shawn said when he got off the phone. The court had denied Kevin’s plea for a stay of execution. At that point, we expected the execution to continue as scheduled and assumed we would be escorted to the viewing area fairly soon. That did not happen. We continued to wait and at one point, one of our escorts, a blonde woman, said “If it looks like we don’t know what we are doing, that’s because we don’t know what we are doing.” They had also never experienced a delay in prior executions.

Kirkwood Police Department/Rachel Bee

Kevin Johnson (right) shot and killed Sgt. William McEntee (left) on July 5, 2005.

We simply sat and waited. Conversation had stopped and we all sat silently, waiting, and thinking about Kevin and thinking how hard this delay must be for him. Then the blonde employee opened a white three ring binder and told us she needed to read us a description of what would happen.

We would be escorted to the room, would be seated and were asked not to have anything other than minimal quiet conversation.

There would be two sets of curtains, one on either side of the glass, that would be opened when we were settled. She told us Kevin would be able to see us, which was not what all of us had been told by Kevin. He thought it would be one way glass and he would not be able to see anyone.

I then asked if we would be in the same room with the victim’s family and witnesses, and she assured us that we would not have any contact with them at all. The dark-haired woman added that they take great precautions to make sure the state’s witnesses and the prisoner’s witnesses never see each other.

I thought about that later and realized each set of witnesses were given different times to arrive on the property, were guided to reserved parking spots on opposite sides of the property, and were escorted at different times to different rooms.

In the room, there were two sets of three chairs that faced the curtained window. The dark blue, pleated curtains were closed, with a prison guard standing at each end. They faced toward each other and did not interact with us. However, one of the guards did move the box of tissues and the trash can closer to Kevin’s brother and sister who were seated in front.

In a carefully orchestrated process, one guard opened the curtains by walking from right to left as the other guard took his place, basically swapping positions. Then the beige curtains inside the execution room were opened. Kevin was lying on what looked like a bed with pillows under his head and a sheet and blanket covering him. Reverend Darryl Gray was sitting next to Kevin with his hand resting on Kevin’s left shoulder. Kevin’s brother stomped his feet loudly so Kevin could hear, or perhaps feel the vibration, to know we were there. He looked and saw all four of us.

The fifth witness chair was vacant because his daughter Khorry was only 19 years old, the same age Kevin was when he committed the crime. State law said a witness must be at least 21 to view an execution. The ACLU had filed a case on her behalf seeking permission for her attend her father’s execution. Her request was denied, thus the empty chair. Ironic, isn’t it? The state can kill you for a crime you committed as a teenager with a brain that is not fully developed, but at 19, you are not mature enough to watch the state kill your father.

Kevin and I had talked many times about Khorry viewing his death, and he insisted he wanted no one in the witness area. “I don’t want anyone to have to see that. I won’t be able to see anyone anyway.” I countered with a plea to attend so that he would know someone who loved him and cared for him would be there for him, even if he couldn’t see me. He continued to tell me no until about one week before the execution when he told me my name was on his witness list.

When Khorry and I talked with her dad the morning of his execution, we left him with three important things to know ... that he will experience the “peace that passes all understanding” in those final moments, that what he sees at that moment is Khorry and Kaius and those sweet smiling faces, (Kaius was smiling a huge smile when we said that), and lastly, that he leaves this life with the assurance that his daughter and grandson will not be alone, that there are many family members and friends who will be walking this journey with her.

While Khorry waited outside, the four of us inside watched as Kevin took his last breath. Reverend Gray touched his shoulder, and appeared to read scriptures and pray. The curtains on both sides of the glass closed again for the medical team to come in, examine Kevin, and determine that death had occurred. When the curtains opened once again, Reverend Gray was not in the room, and we saw Kevin, lying there, with his glasses on. He looked like he was sleeping, very peaceful.

I had a minute with Shawn before he left and thanked him for all he has done and for being such a comfort tonight. I had told him earlier “don’t be nice to me because I will cry right now” but we did manage a “don’t be nice to me” hug before he left. Kevin’s brother and sister and I got in my car and proceeded to the exit. His sister lamented the fact that they all had been dealt a bad hand since birth.

We returned to the field and the gravel drive and Kevin’s brother and sister got out. I parked the car on the side of the road and walked back. Khorry is the first person I saw and she gave me a big hug and told me that when it was 7:40 p.m., the wind really picked up outside, and she felt like that was her daddy telling her he was okay. After a few minutes, most of the cars were gone. I walked back to my car and began the hour and a half drive home.

The next morning, November 30, I found an email from Kevin that was the last email he sent. I definitely was not expecting an email from a dead man. He had been emailing me daily what would eventually be the third book in his trilogy, titled Journey to the Gurney. In this book he documented the pre-execution phase, describing what was happening each day and what he was thinking and feeling. He last words were for all those who cared for him and fought for him.

“In the aftermath of my demise, I want all of those who have supported me to know I am appreciative of them. Their undying support for both me and my daughter gave me the strength to keep fighting. Although my fight is over, the fight for this cause is never dying. Continue to stand up to racism. Continue to change the narrative." — Kevin Johnson 11-29-22

At the RFT, we welcome well-reasoned essays on topics of local interest. Contact [email protected] if you've got something to say.

Coming soon: Riverfront Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting St. Louis stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter