For many journalists, including DW Gibson, Studs Terkel's Working, originally published in 1974, remains a touchstone. Terkel took his tape recorder out into the streets of Chicago and interviewed some 200 people about what they did all day and how they felt about it, and then edited their responses into a series of monologues.

A few years ago, Gibson and his friend Colin Robinson, a book editor, were discussing Terkel and Working. Gradually the conversation turned to the Great Recession and Robinson's own experience being laid off from his editing job at Scribner's in November, 2008, a day known in the publishing world as Black Wednesday.

"The story had all the familiar touchpoints," Gibson recalls now. "He got the call to come into the office and had a bad feeling. He said, 'When they closed the door, I felt worse. And when they told me to take the comfortable chair, I knew.' And then he found himself comforting the people who were giving him the news."

Gibson felt sympathy for his friend. But he also saw something else. "I recognized something helpful and hopeful in the telling," he says.

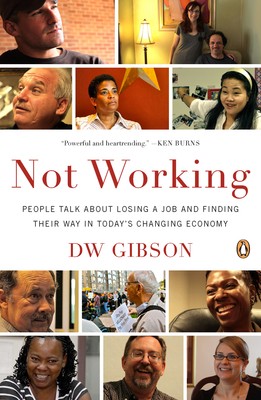

That was an idea that Terkel, who died in 2008, might have recognized as well. And thus a book was born, a Working for the recession called (naturally) Not Working, out two weeks ago.

Last summer, Gibson and two friends, Mallery Avidon, a playwright, and MJ Sieber, a filmmaker, and, occasionally, Gibson's wife Tasha Garcia Gibson (when she could get time off from her own job) piled into an un-air-conditioned Jeep and set off on a cross-country story-collecting odyssey, from Orange County, California, to Camden, New Jersey, including a stop in St. Louis.

"We found people by every means," Gibson says. "Soup kitchens, professional networking, church. We went to church a lot. We went to unemployment offices and stood outside in line in the Fresno heat and the St. Louis heat. We talked to beat reporters from the local papers, who turned out to be very helpful, Facebook friends, everyone we could think of. When we weren't talking to someone, we were looking for someone to talk to. We worked all day, eighteen-hour days. We ran on adrenalin."

In the end, they interviewed 200 people for the book; 70 of those interviews were also filmed for a documentary. In the basic outline, the interviewers found, many of the stories were very similar, but once they delved deeper and unique details emerged. "Everyone brings something new," Gibson says.

The purpose of the project was perhaps best articulated by a draftsman from West Des Moines, Iowa, who had been laid off three times within the span of eighteen months. When Gibson, Avidon and Sieber met him, he was holding himself together by working three jobs: a paper route in the middle of the night and cashier jobs at Tru-Value Hardware and a Hy-Vee grocery store during the day.

"People would come into the Hy-Vee and say to him, 'Didn't I see you at the hardware store this morning?'" Gibson recounts. "And then he'd have to explain [that he'd been laid off]. At first it was hard for him, but then he started to become the person other people came to to talk about their own unemployment stories. They weren't alone anymore. He started to feel a sense of community."