Introducing the Legendary Bob Reuter, Five Years After His Death

Five years ago Bob Reuter knew full well: There’s nothing fair about life.

In a lot of ways he really couldn’t complain. Sure he was in his sixties and always flat broke, but he had his own radio show on KDHX where he could raise an unholy ruckus and work out his personal demons in front of the whole city. He had a bunch of punks half his age who not only knew what a great and gritty songwriter he was but had built themselves into a band for him, then threw him in a van and brought his cranked-up rock & roll romanticism to whatever dive bar would have em.

He had a little old Pentax SLR camera, nothing digital about it, that had memorialized thousands of beat up buildings, hard luck cases, foxy punk musicians, iced-up alleys — so many of the city’s dark corners and the people found there. He had a darkroom at Tom Huck’s Evil Prints Studio where he could set up an enlarger and developer trays and spend all night printing photos, instantly recognizable by their filed-out edges and sprocket holes, their black and white grain and their clumsy, unprofessional but undeniable power. There was both a little publishing house and a monthly magazine that were not just willing but eager to publish his endless grimed-out stories and poems.

He had an audience, he had venues for his work, and he had a lot to say. He had even gathered up all his shit and was moving it all into an old warehouse downtown where he knew he’d be able to print photos and write all night and work on songs and finally get to be as productive as he always meant to be. 61 years old and it felt like the world was finally picking up what he was laying down.

And that of course was the moment, right there at the brink of his next chapter, when he stepped into an empty elevator shaft in that old building and suddenly reached the very last page of his story.

Five years on, and there’s nothing fair about death either.

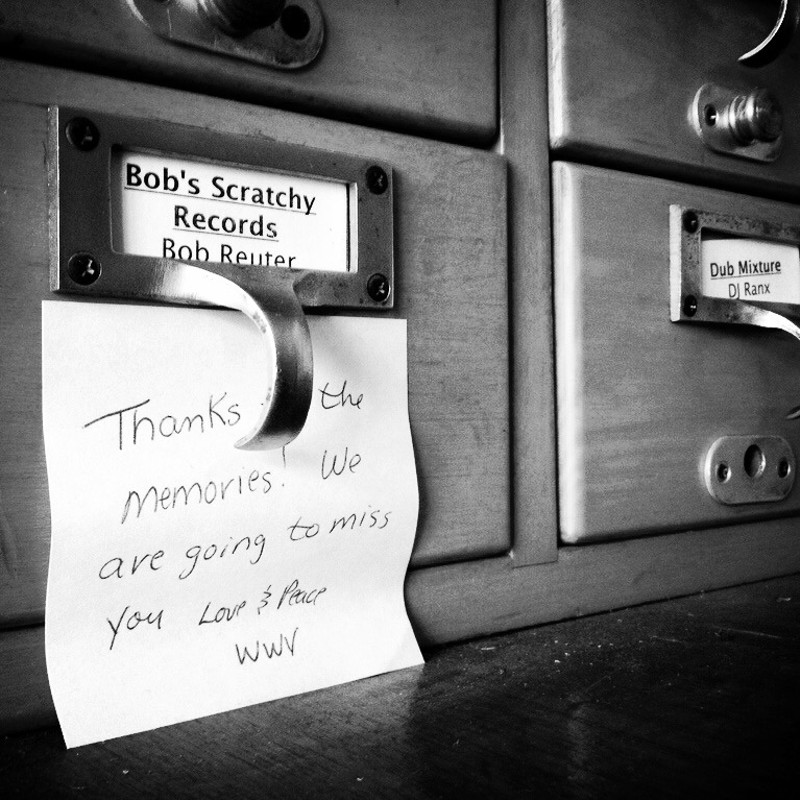

In 2018, I have so many friends in the city who have never heard the songs of Bob Reuter, never heard him yank a needle across a record live on air during Bob’s Scratchy Records, never answered his desperate pledge-week plea to “put your hands on the radio,” never read his stories or heard the Ray Scott song that goes, “And if that’s not bad enough for the guv’nor…” They’ve never seen his iconic, strung out, miserably elated street punk photos glorifying the alleys and gutters and beautiful dirty denizens of a St. Louis they’ll never get to meet. They live in a different city than those of us who knew Reuter’s work.

And that drives me crazy. We haven’t just been living without Bob Reuter the person for the last half decade, we’ve been living without the story he was telling, without the city that he was making up around us. Post Reuter, sometimes the music scene here feels like an abandoned novel, a story stranded without an author. Not that there aren’t plenty of great bands making great music — there always has been great music in St. Louis and there always will be — but the giant narrative arc that he spent so long building, across so many formats, is broken.

Or maybe, I guess, it’s just complete? Everybody dies somehow, and if nothing else, Reuter’s death was a shock as big as his life, and thus maybe somehow fitting.

This week, I’ve been wanting to introduce those friends to Bob Reuter the person and Bob Reuter the artist and Bob Reuter the hellraiser. I’ve found myself fantasizing about a book. It’s a big book, a deluxe coffee-table edition: glossy dust jacket over a black cloth binding with debossed gold-leaf cover type that reads Rockin Our Lives Away: Bob Reuter’s St. Louis. There’s an introduction by Tom Huck and extended essays by both good friends of Bob’s and by art historians who write at length about the way these photos both reveal and summon the secret life of the city.

On each right-hand page is a single photo, shown on whatever scrap of paper it was originally printed on. Each left-hand page is a small note — maybe written by the subject of the photo, maybe something Bob said about it, maybe just the year that the photo was taken. It’s broken into chapters, each fronted by a lush two-page spread featuring a blown-up detail from one of his prints. It contains all of his published short stories and poems, and transcriptions of passages from the radio show.

On the inside front cover there’s a large pocket sleeve holding an LP full of songs by the Dinosaurs, Thee Dirty South, Kamikaze Cowboy, Serious Journalism and Bob Reuter’s Alley Ghost. A matching sleeve on the back gathers a vinyl best-of collection of the great stories, terrible jokes and signature song selections that made up Bob’s Scratchy Records.

This book would be available at Left Bank Books, of course, so that anyone in St. Louis who wanted to could go to the music section and find the legend of Bob Reuter prominently displayed alongside the legends of Bruce Springsteen, Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Lester Bangs, Gil Scott-Heron, Jim Carroll, Malcolm McLaren, Serge Gainsbourg and the rest of his contemporaries. And maybe there’d be a copy in the photography section alongside the work of Mick Rock, Diane Arbus, Weegee, Charles Peterson and Larry Clark.

But this book could also be found on the shelves of City Lights in San Francisco, the Strand in New York, Powell’s City of Books in Portland OR, Shakespeare and Company in Paris, the Library of Congress. This book would be a document of an American city at the height of its grimy powers, captured at its most unselfconscious and legendary. It would be a revelation to anyone who came across it, revealing analog rock & roll in full swing and every bit as seductive as ‘60s San Francisco, ‘70s NYC or ‘90s Seattle.

Bob Reuter would probably hate this book for its pure size and pretension. At least at first.

I want so badly for this book to exist. I want to see it in living rooms around the city; I want people in other cities, in other countries, to know those stories. I want people in other decades to know those stories. In fact, I would be OK if, one hundred years from now, Bob Reuter’s stories, photos, songs and broadcasts were the only surviving record of St. Louis in this time. What he caught in those photos of friends and musicians and brick buildings and smoke-filled summer nights right at the bottom of the top of the dirty South, what he said every week on the radio, whether he was lunging around the studio throwing records or muttering darkly about a dream he had earlier that day, what he caught in those songs and grimy poems: That all stands for a century’s worth of information about this place and time.

The fact that he’s dead at the moment, that he’s been dead five years now even — from a hundred years’ distance, who would even notice?

Evan Sult is RFT's art director. He misses his old friend dearly.