"Aaaaaaahhhhhrrrrr!" screams Devon Alexander. It is January 29, 2011, two minutes into the tenth round of the biggest fight of his career and, by his count, Tim Bradley has just headbutted him for the sixth time. This one was particularly painful.

The referee calls "time" and Alexander staggers into the neutral corner, grabs the ropes with both gloves and squats into a crouch, grimacing. Bradley has a reputation for being clumsy with his skull, and several times during the fight Alexander's trainer, Kevin Cunningham, called out to the ref to watch the headbutts.

The ringside physician climbs onto the canvas and looks at Alexander's face. Alexander squints.

"Gotta open up your eyes," pleads Dr. Peter Samet.

Alexander takes a step backward and hops up and down a few times. Boos begin raining down from the Pontiac Silverdome stands.

This bout is one of the most hyped in years. It is the first time in nearly a quarter century that two undefeated American champions faced off to unify their belts. This morning, St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist Bryan Burwell wrote, "A lot of people are comparing this championship fight to a potential redo of the slugfest between Marvin Hagler and Tommy Hearns in 1985. But a better comparison might be the first Ray Leonard-Hearns battle."

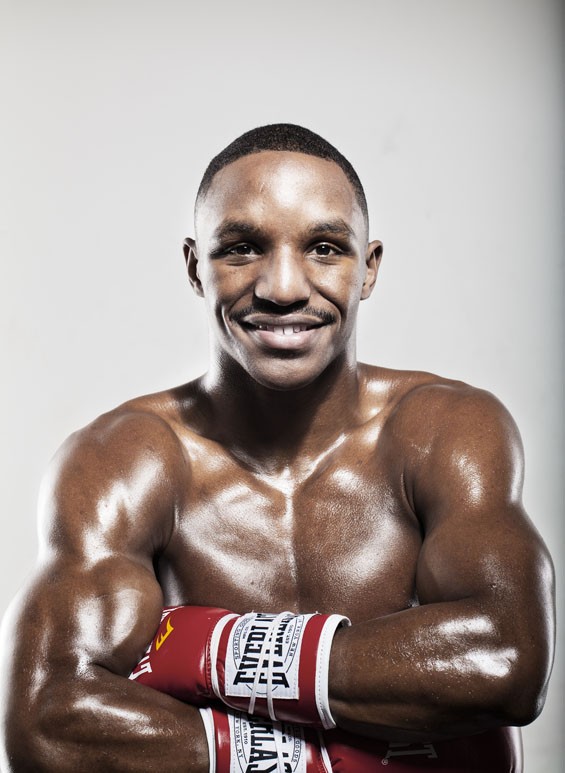

The 27-year-old Bradley came into the fight as the 26-0 WBO light welterweight world champion, feared for both his Rottweiler tenacity and his awkward style. And Alexander, at 23, entered as the 20-0 WBC light welterweight world champion, christened as most promising boxer of his generation. ESPN boxing writer Dan Rafael called him "the young American fighter who has the most Floyd Mayweather-like potential." HBO color commentator Max Kellerman declared that Alexander just might become the best pound-for-pound boxer in the world one day, a likely nominee to snatch the prizefighting crown whenever Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather Jr., the current kings of the sport, decline or retire.

Alexander had the kind of Horatio Alger tale that made sentimental sportswriters swoon. The New York Times chronicled his path from north St. Louis' violent Hyde Park neighborhood to boxing champion. So, too, did Sports Illustrated. A win over Bradley would cement his status as the best 140-pound boxer on the planet.

But now it is all slipping away. The doctor wipes Alexander's left eye with a crumpled tissue. HBO's camera zooms over Samet's shoulder into a close-up of the boxer's face. Alexander's squint tightens.

"Can you open up your eye?" asks Samet.

"Nah, that shit hurt, man," Alexander cries back.

"Both eyes, open up. Both eyes, look at me."

Alexander raises his lids for a second then furiously blinks, his head tilted toward the rafters.

"Ah, fuck!" he exclaims.

"If you won't open up both eyes, everything's over. Your evening's over."

"Fuck. It burns," Alexander hisses, shaking his head from side to side as if he were trying to get water out of his ears.

"Look at me. Look at me. Open your eyes."

"Aaaahhrrr."

Still squinting; still grimacing.

Samet shifts his gaze toward the ref, waves his hands, and tells him to stop the fight. Bradley, ahead on all three of the judges' scorecards, is the new unified 140-pound world champion.

Later in the evening Alexander tells reporters, "If the doctor said I could go on, I would have gone on." Samet backs up that storyline, explaining, "It was more than a cut. I was worried that it was a nerve and that his eye was paralyzed."

Many in the boxing world saw something else, though.

The next day, ESPN.com's boxing section features a large photo of Alexander, right brow bleeding from a deep gash, left eyelids scrunched together. The caption reads: "Afraid of a little blood? Devon Alexander showed little heart in relinquishing his title to Timothy Bradley." The fight is so anti-climactic, in fact, that HBO chooses not to activate a rematch clause.

Rafael writes, "As much hype as the fight received and as much hope as there was for a memorable battle, watching a fighter essentially quit in the biggest bout of his life is disappointing." Eric Thomas of BoxingNews24.com writes, "It's hard to see it any other way than Alexander flat out quitting." Post-Dispatch columnist Bernie Miklasz writes, "Alexander 'The Great' flunked his first national showcase, getting overwhelmed in an embarrassing loss to Bradley." Light welterweight rival Paulie Malignaggi tweets, "You quit like the punk most of us suspected [you] always were."

There is no worse stain on a fighter's career than to be labeled a quitter. A year later, Alexander is still trying to shake it.

"I could have continued the fight," he acknowledges now. "But I knew I had a rematch clause, so I decided to take that path."

Thinking back to that night in Detroit, Alexander's eyes — including the one temporarily blurred from the headbutt — fill with regret. Given a mulligan, he says, he would handle things differently.

"I would have definitely fought with one eye," he asserts. "This is boxing. You gotta put your life on the line. You put your life on the line every time you're in the ring."

On February 25 at the Scottrade Center, Alexander will put his career, if not his life, on the line when he fights Marcos Maidana, the most devastating puncher in the division and perhaps his most daunting opponent yet.

An impressive performance will make Alexander a championship contender again, dumping him back on the path to the mega-fights. Anything less and he inches toward that long list of flash-in-the-pan fighters who captivated the boxing world for a shining moment before fading away into undercards and "Where Are They Now?" specials.

"This is gonna mean, does he have any place to go from here?" says longtime St. Louis boxing trainer Jim Howell. "Fighters live and die on these kinds of fights."

It's time to get grimy!" yells Cunningham.

The trainer and his boxer have been holed up for weeks in the musty seclusion of this teal metal gym in suburban St. Charles.

"Just how we like it. Nothin' but steel beams and bags, sweat and blood," continues Cunningham. "Perfect. Yeah, 'cause that's what we're getting ready to do, get grimy with this dude. So it's time to get grimy!"

Medicine balls wrapped in duct tape, stray jump ropes, and rusty dumbbells litter the concrete floor. The only natural light streams through a small tinted window on the door. The door that remains locked at all times.

Camp is closed to the public. This is a big fight, carrying high stakes, and the last thing Alexander needs is some misguided fan wandering in to tell him how great he's looking.

"Bring that hook all the way across your chest," commands Cunningham.

Alexander lets off a better right hook, then wipes his brow with his wrist.

"Come on, don't worry 'bout no sweat!" shouts the trainer.

"Want me to see, don't you?" retorts Alexander. And there goes that sly grin.

The boxer's smile is as much a part of his persona as his hand speed and that Cardinals fitted cap he wears for every ring entrance. It persists through weigh-ins, pre-fight press conferences, and just about every interview he's ever done. So it sometimes seems as if he doesn't feel the immense pressure of a career-defining fight.

In the lead up to the Bradley bout Alexander and his opponent participated in a sort of roundtable discussion with Kellerman for HBO's promotional "Face Off" segment. Bradley spoke with a determined scowl, maintaining the stern monotone of a politician addressing a corruption scandal. Alexander seemed to get a kick out of the whole spectacle and within minutes was trying to hide his mouth behind his wrists to hold in the laughter.

"January 29th, you'll be dethroned, king," declared Bradley, with a look of forced menace.

"I'm a warrior," Alexander mockingly corrected with a smirk. "Alexander 'The Great' was a warrior."

Alexander's lighthearted demeanor should not be confused with indifference. Ask him about his ability and his usual humility is, for a few fleeting seconds, supplanted by statements like, "I wanna be one of the best of all time."

As he punches and shuffles around the ring, the stereo blares "Headlines" by Drake, the rapper who accompanied Alexander to the ring before he knocked out Juan Urango in March 2010.

"And they saying I'm back, I'd agree with that...

I had someone tell me I fell off, ooh I needed that/And they wanna see me pick back up, well, where'd I leave it at/I know I..."

Cunningham switches off the music. Now the trainer's voice serves as the soundtrack.

"Speed, quickness. Speed, quickness. That's what I want. Your hands stop, your feet should be moving. Your feet stop, your hands should be moving."

Cunningham has brought in hard-hitting sparring partners with similar styles to Maidana — a slogging pugilist with a nasty right hand. One of them plods toward Alexander like a water buffalo marching through a swamp. Alexander pops a couple of jabs that smack his foe's head. He sticks and slides, landing flurries every few seconds. Then the sparring partner pressures him into a corner and slams a wide-swinging hook right into Alexander's nose.

"Mmmhmm," says Cunningham. "See when you sit yo ass down in front of that right hand. That's what you gon' get."

Blood drips onto his shirt and his shorts. When the round ends, Alexander blows a red snotty mess toward a bucket under the corner post. But because he is hastily bouncing up and down on his toes, the globs fly errantly, spraying remnants onto his trainer. Cunningham thinks Alexander looks tense, anxious maybe. The big fight is just three weeks away.

"Gotta be more relaxed man," he demands, wiping his shirt. "You're all jittery. Using too much energy. You gotta settle down man. You're too wound up. Get yourself together."

In each of his last three fights Alexander's legs seemed to grow heavy as the rounds passed, often forcing him to abandon his fast-paced boxing style, which relies on constant movement and precise footwork. He and Cunningham say that this was because the frantic push to make weight drained his energy. He had outgrown the 140-pound division — the weight at which he has fought since he was a teenager. He walks around at 165 pounds and trains at 154. It was time to move up. He will fight Maidana at 147 pounds, in what will be each man's welterweight debut.

Alexander and Cunningham also believe that dropping to 140 sapped his punching power, which in the boxing business is not just a tool to win fights, but a feature that draws crowds and profits. And right now not a lot of people think Devon Alexander delivers anything more than pitter-patter.

"The problem with Devon is he's not a big puncher," says Rafael, the ESPN writer. "He doesn't make exciting fights. His strength is his consummate boxing, fast hands, enough power to keep you honest, and sometimes that doesn't translate so great to TV. He's not gonna typically be the type of opponent you're gonna look at and say, 'Oh my God, he's gonna be in the fight of the year.'"

Marcos Maidana, 31-2 with 28 knockouts, has produced a good number of fight-of-the-year candidates. Three, in fact, over the past two-and-a-half years alone. During one of those, in June 2009, "Vicious" Victor Ortiz knocked Maidana down three times in the first two rounds. But Maidana recovered and pummeled Ortiz so badly that he quit midway through the sixth.

Ortiz is a prime example of how a single fight can erase the "quitter" cat calls. He followed the Maidana loss by winning a savage four-knock-down brawl against undefeated star Andre Berto. And, just like that, five months later Ortiz found himself in a mega-fight with Mayweather. (He lost in a fourth-round knockout.)

After Alexander finishes sparring on this February afternoon, the talk in the gym turns to the big news of the day. Cunningham just got word that Bradley will fight Pacquiao in June. It is so obvious and painful that there is no need for anyone to mention the connection: In a parallel universe where Alexander defeats Bradley, this would be his match.

Cunningham posits that Bradley has a chance to win because he is such a slick boxer, difficult to hit. And nothing frustrates an aggressive fighter more than a slick boxer who is difficult to hit. Cunningham saw this first-hand when he trained Cory Spinks, one of the slipperiest boxers he's ever seen, to a world title.

The trainer and the ex-champ had a falling out a few years back. To Cunningham's mind, Spinks — a St. Louis phenom whose father and uncle made names for themselves in the heavyweight division a generation earlier — could never truly dedicate himself to the constant conditioning the sport requires. So now, six years after fighting main event championship bouts, Spinks is hobbling along on untelevised undercards before Alexander showcases or headlining matches at a Shriner's temple downstate in Springfield.

"If Cory had discipline, ain't nobody coulda hit him," says Cunningham. "You couldn't have hit him with a bag of rice. If he coulda said 'I'ma see how far I can take this,' man..."

He shakes his head.

Alexander has the discipline. But, the boxing world wonders, does he have the grit and talent to make it back to the top?

By now most everybody knows the story behind the Fighting Pride of St. Louis.

Seven-year-old Devon walks into the north St. Louis boxing gym that Cunningham, a former narcotics detective, is running for troubled youth in the basement of a vacant police substation. The kid burns through the amateurs and becomes a world champion in the pros by the time he's 22. Most everybody also knows the famous statistic: Of the 30 kids who trained beside Alexander under Kevin Cunningham's guidance, ten are now in prison. Nine are dead, swallowed by the violence of the St. Louis streets.

Alexander was 19 when he made his national television debut, winning the WBC youth welterweight title with a first-round knockout. He splashed onto the boxing scene a year-and-a-half later, after beating skilled veteran DeMarcus Corley in Madison Square Garden to win the WBC Continental Americas light welterweight title on the undercard of the Roy Jones Jr. v. Felix Trinidad pay-per-view.

In August 2009, he got his first big title shot, against Junior Witter, a slick Brit whose only losses had come from Zab Judah and Tim Bradley. Alexander took Witter to school, sticking and moving round after round, peppering him with so many stiff jabs and punishing him with so many jarring right hooks that Witter threw in the towel after the eighth.

Alexander burst into tears as Cunningham embraced him. He slept that night with his new WBC light welterweight championship belt cradled in his arms. When he returned to St. Louis, Mayor Francis G. Slay awarded him the key to the city.

In his first title defense seven months later, Alexander unleashed his fierce right uppercut and knocked out IBF light welterweight champion Juan Urango in the eighth round, adding that belt to his collection. It was the first time any man had KO'd the iron-chinned Colombian. The fight was as rugged as the ending was spectacular, with the boxers trading blows whenever Urango bulled inside Alexander's jab. But Alexander controlled the tempo, limiting those exchanges by gracefully sliding around the ring and firing off blistering combinations as Urango attempted to crowd him.

During the post-fight interview, Kellerman, the HBO commentator, praised Alexander, declaring, "You are choosing to fight in a laudable style. You're not running. You're not holding. You're choosing to do the hardest thing in boxing: stand right in front of your man, stick and counter."

Later that night, Alexander received a phone call from Floyd Mayweather Jr. "I just wanted to tell you," the proud champion said, "when I pass the torch, I'm passing it to you."

Boxing had a new star. In the next morning's Post-Dispatch, Miklasz gushed, "Alexander has unofficially been anointed as one of boxing's next-generation stars...He has a crowd-pleasing style. He aggressively sets up in the middle of the ring to engage his opponent...He fights with heart. And that sells tickets and draws viewers."

If Alexander were to retire today, the Urango fight would be considered his peak. It wasn't long before the fall.

His next fight, against Andreas Kotelnik in August 2010, was supposed to be a coronation of sorts. It was his first big time fight in front of his hometown fans, the biggest boxing event in St. Louis since Cory Spinks fought Zab Judah in front of 22,000 people five years earlier. A nine-to-one favorite, Alexander was to showcase his laudable style and demolish Kotelnik the way he had demolished Corley, Witter and Urango. It didn't work out that way.

Kotelnik baffled Alexander with his European-style, square-footed defense and squeezed in power shots at each rare opening. While Alexander threw nearly 300 more punches, he landed on less than twenty percent. His work rate would pay off, earning him enough rounds for the judges to award him a unanimous decision. Yet many boxing writers and fans agreed with Kotelnik when he said after the match, "If the fight were anywhere else but here, I would be champion."

Kellerman, who thought Kotelnik won, dubbed the champion "Alexander 'The Good.'" Miklasz, who thought Alexander won, wrote, "Had Kotelnik been awarded the decision, I wouldn't have complained."

Six months later came the Bradley match, in which he suffered his first loss and got tagged with the "quitter" label. Almost as bad, many thought the fight was boring as hell. Because Bradley appeared to be the aggressor most of the time, Alexander carried the blame for the dud.

The doubts lingered through his next fight when Alexander faced off against Lucas Matthysse last June in St. Charles. After Alexander controlled the first three rounds, Matthysse knocked him down for the first time in his career in the fourth. Alexander rallied, though, and the two men fought an exciting and tightly contested match, ending with a bruising punch-for-punch finale. Alexander won by split decision, pushing his record to 22-1. But, for the second time in a year, many viewers, including HBO announcer Larry Merchant, disputed his victory.

What almost everyone could agree on was that Alexander's star had dimmed since the Urango knock out.

"He's had three fights where a lot of people think he's 0 and 3," says Rafael, quick to note that he believes Alexander rightfully won both hometown decisions. "To be honest, he's shown that he may not be as good as a lot of us thought he was."

When the details of the Maidana fight were announced, its location immediately stood out. St. Louis is the city that will draw the biggest crowd for this bout, the city in which Alexander's fame was built. But it is the city that played a role in denting Alexander's reputation as a fighter.

"You have to wonder if Maidana knows the history of Alexander's fights in St. Louis," wrote Michael Collins, at the boxing news site EastSideBoxing.com, echoing the sentiments of many sportswriters. "If he did, Maidana would have to be dragged kicking and screaming all the way to the Scottrade Center."

Alexander admits that his last three fights have strayed from the script that accompanied his ascent to the national stage. Still, by most measures his career has been an astounding success.

He escaped poverty. He fought on Showtime and HBO. He was crowned world champion. He raked in more than $3 million in purses.

Last year he became the first member of his family to own a house. When the afternoon training session is finished, Alexander drives his charcoal Dodge Charger the five minutes it takes to reach his St. Charles subdivision. The decor inside the four-bedroom home could be described as minimalist.

The only indicator of the resident's profession is a solitary Alexander v. Maidana promotional poster lying on a table in his dining room. Down in the basement, past the pool table and flat screen, in a room littered with children's toys, a stack of photos and portraits celebrating his in-ring accomplishments leans against the wall.

Alexander has three kids, ages two, five and six, who live with their respective mothers but often stay with their father. Recently Alexander tore through the suburban dad to-do list, redoing the deck off the kitchen and installing a jungle gym in the backyard.

One might even call his life dull. His mother does.

"My mom says I'm boring," confesses Alexander, as he plops on his living room's black leather couch. "I never was a crowd type of guy, being around people and stuff. I never got into drinking and smoking, never really went to clubs. When I was younger I went to a club a couple of times and I was just like, 'This is it?' It wasn't all it's cracked up to be. I'm with my family a lot."

He's been that way all his life. The fourth youngest of thirteen kids, Alexander grew up sharing a bedroom with two brothers. His dad worked at a grocery store. His mom was a day care provider.

"Devon's always been a kid that really didn't need to hang out with the crowd," says Darryl Bradley, his eighth-grade science teacher and a certified chiropractor who now serves as the fighter's doctor during training. "He has a really good family support system, and coming from the neighborhood we were from, that was really lacking."

When Alexander recalls his days amid the crime, gangs and drugs of Hyde Park, he sometimes notes tragic details with a sheepish grin that a psychiatrist might diagnose as "developed desensitization" but friends might chalk up to his inherently cheerful disposition.

"I used to spar with my friend Terrance— he's dead now— and he used to make me cry, hit me in the nose," he says.

Alexander instantly took to boxing, showing up at the gym every day after school. He won his first tournament at the age of 10 and the Golden Gloves Junior title at 14.

"Once we started boxing, oh my god, that was all we did," says his 30-year-old brother Lamar, who also boxed under Cunningham and now works as his assistant trainer.

It was in eighth grade when Alexander missed his first day of training. Cunningham got word that he was trying out for the basketball team, even though he had a tournament coming up. So he got in his van and went straight to the school.

"Lemme tell you something," Cunningham told him as they drove back to the gym. "You got an opportunity to be one of the best young fighters in the country. You could be a jack-of-all-trades and master of none, or you can focus, do it all the way and be a master at boxing."

Alexander hasn't missed a day of training since.

He became one of the stars of Cunningham's renowned stable of boxers. At a 2002 Silver Gloves tourney, three of Cunningham's fighters took home belts. Alexander was one of those fighters. The other two are no longer boxing. Quintin Gray got a life sentence for murder, and Willie Ross was murdered.

In 2004, after rattling off a 298-12 amateur record and accumulating numerous titles, 17-year old Alexander was the No. 1 seed at the U.S. Olympic trials tournament. He lost a controversial decision to 21-year-old Rock Allen. Cunningham was furious. He believed that U.S.A. Boxing's shot callers favored Allen because they wanted to send a veteran fighter to Athens.

The fight would be Alexander's last as an amateur.

"The next punch you throw," Cunningham told his fighter that day, "you'll be getting a check for it."

A few fights into Alexander's pro career, his father, then in his early 50s, died of prostate cancer. It was the worst day of his life, he says. Lamar, immensely distraught that he would never again see his father ringside, retired from the sport. Devon did the opposite.

"He dealt with his father's passing by driving deeper into his training, deeper into boxing," says Cunningham. "He escaped."

About a year later, Alexander's older brother Vaughn, whom he followed into Cunningham's gym at age seven, was convicted for armed robbery and assault. Even these days, each time Alexander visits his brother at Potosi Correctional Center, it takes a little bit out of him. Vaughn is currently seven years into an eighteen-year sentence.

"I hate having to drive an hour-and-a-half to see my brother, when I used to wake up to him every day," says Alexander. "I can't wait for the day he gets out."

Alexander admits he doesn't have many friends outside of his family. One time early in his pro career he caught a guy he considered a friend trying to steal $600 from his home.

"I told him, 'Just give it up and get out,'" he says, maintaining that constant smile. "That's why I don't have many friends. I have associates. I have enough brothers that I don't need too many friends."

Alexander's phone buzzes. Someone has emailed him a link to an article headlined, "Team Victor Ortiz Eye the Alexander vs. Maidana Winner." He lets out an amused laugh. He still finds it surreal that people he's never met talk and write about him.

He turns on the TV and flips to CNN, where Anderson Cooper and David Gergen are analyzing the results from today's Florida Republican presidential primary.

"Mitt Romney pays nearly no taxes!" Alexander blurts, soaking in the experience of being the one talking about rather than the one talked about.

"I was kind of skeptical of Republicans on the tax bracket," he says. "I remember when I was growing up in north St. Louis, I kept thinking about how unfair it was that there were some rich people out there paying less taxes than what people around me were paying."

He pauses and the smile widens.

"But now that I'm in this tax bracket, I'll give it to the Republicans on that one," he jokes.

One of the talking heads on TV mentions that Romney is in for a "slugfest" with Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich. Another adds that primary season will leave the former Massachusetts governor "bloodied" by the time the general election rolls around.

Alexander laughs out loud when he hears these metaphors. What do these politicians and journalists in designer suits know about slugfests and getting bloodied?

What do they know about getting in a ring with a relentless Argentine scrapper with hammers for hands who has knocked out 28 of the 33 men he has fought and wants to beat you unconscious and pound your career into oblivion?

It's about a week before the fight. Devon Alexander wakes up at 6 a.m., throws on his sweats and runs five-and-a-half miles.

Tension between the fighters has been growing. A few days earlier the Maidana camp threw out allegations about Alexander taking performance-enhancing drugs.

"There are heavy rumors out there about possible use of PEDs," Maidana's advisor Sebastian Contursi emailed Tim Lueckenhoff, the executive director of the Missouri Office of Athletics. "What could be better to throw those rumors away in the most transparent fashion than performing a drug test before and after the fight?"

Cunningham was incredulous and pissed. He emailed Lueckenhoff, "Devon will take any test, anytime."

Alexander laughed it off. But it's personal now.

After the run Alexander stretches and completes a circuit of pull-ups, push-ups, sit-ups and resistance-band strength work. Then he eats breakfast.

There are now rumblings that the winner of Alexander v. Maidana might just get a mega-fight shot against Floyd Mayweather Jr. in the fall. Nobody is talking about what happens to the loser. Alexander certainly isn't. Asked what will become of him if Maidana's punches prove to be too much, Alexander jabs back with unwavering confidence.

"A lot of guys hit hard," he says. "But I hit hard, too."

The fighter is back at the gym by 12:45 p.m. for three hours of shadow boxing and heavy bags and sparring. Then dinner. Then another workout at 7 p.m. and lights out by 10. Rinse and repeat.

The routine has consumed his life for nearly twenty years. So long that it is the stretches in between, the protracted days without the urgency and pressure of a looming fight, that feel peculiar.