Getting elevated to national treasure status is about the worst thing that could ever happen to anybody. Suddenly a person turns into a symbol, a collection of slogans and postures, and it's hard to forget that there was a living, beating heart inside that statue.

This year marks the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Woody Guthrie — the actual date is July 14 — a National Treasure if there ever was one. This is, after all, the man who gave us "This Land Is Your Land," a song that has frequently been suggested as a replacement for "The Star-Spangled Banner" as our national anthem, which may not be such a bad idea: It sounds just as good sung by Pete Seeger or Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings or any large gathering of Americans. The words are simple, the tune is simpler, and it's catchy as hell. "Any fool can be complex," Woody said. "It takes a genius to be simple."

That's Woody, the poet of the people who became famous in 1940 with his first album, Dust Bowl Ballads, a collection of tunes that gave voice to the migrant workers he met in California who were forced off their Midwestern farms by the dust storms and, more frequently, the bank foreclosures that plagued the U.S. in the 1920s and '30s. They went west to look for work and found themselves living in dire poverty, "busted, disgusted and mistrusted," in makeshift work camps. "I seen there was plenty to make up songs about," he wrote, "and this has held me ever since."

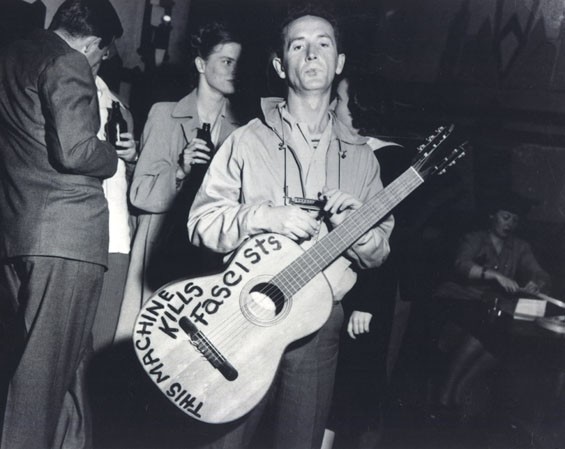

But there's also Woody the socialist, raging against the cops, the government and the bankers, brandishing his guitar emblazoned with the slogan "This machine kills fascists." ("It means just what it says, too," he noted in his diary in 1944.) Look at him in the above photo from 1945, instrument dangling over his shoulder, sullenly smoking a cigarette, appearing for all the world like a modern-day Occupier. This was the Woody who so offended the good people of his native Oklahoma that it was only recently that his hometown of Okemah put up signs acknowledging itself as his birthplace, and the innocuous cowboy tune "Oklahoma Hills" was adopted as the official state folk song.

Guthrie was no doubt aware that, as he became a national treasure, that other side of him would be forgotten, or at least become very well hidden. He was ever conscious of his image, hiding his perfect command of grammar in order to play up the role of the illiterate Okie, never admitting that he only hopped freight trains as a last resort because they were too dangerous and too uncomfortable. In 1964, when he was dying of Huntington's disease, he took his son Arlo out into the back yard of their house in Brooklyn and made him memorize the three "lost" verses of "This Land Is Your Land," the ones about the evils of starving people standing in bread lines and a sign that reads "No Trespassing."

This year the Woody Guthrie archives, long confined to a small suite of rooms in midtown Manhattan, will be returning to Tulsa, to a converted factory where, Guthrie's daughter Nora promises, they will be open to everybody. A small selection of photos, manuscripts, letters, postcards (including one showing a polar bear at the Saint Louis Zoo; Woody drew a guitar in its arms), clothing, guitars and other souvenirs has been culled and set up in a handsome display in the city's Gilcrease Museum. (Later this year the exhibit will be traveling to LA and New York, following in Guthrie's footsteps.)

On March 10, a formidable collection of musicians, including Rosanne Cash, John Mellencamp, Jackson Browne, the Flaming Lips and, naturally, Arlo Guthrie, played a tribute concert at the Brady Theater to kick off the Year of Woody and celebrate the National Treasure. Earlier that day the University of Tulsa hosted a symposium to try to make sense of the man from Oklahoma and figure out what somebody who died in 1967 still had to say about the country we live in.

There's a lot, it turns out.

Woody Guthrie was not a theorist. Despite many solemn resolutions to plow through The Communist Manifesto and other works that formed the foundation of socialism, he never quite made it. He was a literalist: As he wrote on the bottom of the first draft of "This Land Is Your Land," which is on display in the traveling exhibit, "All you can write is what you see."

The first thing he saw was the Oklahoma of his childhood, full of Christian socialists and preachers who taught that men would never be free without their own land, that Jesus was a humble worker and that everyone who followed in His ways was equal. (See Woody's lyric from the song "Jesus Christ": "It was the big landlord and the soldiers that they hired/To nail Jesus Christ in the sky.")

Woody's father, Charles, however, was on the side of the Pharisees and bankers: He was a prosperous land trader, an aspiring politician, a raging anti-Socialist and, possibly, a member of the Ku Klux Klan. The Guthries lived in a house up on a hill in the nicest part of Okemah. The foundations are still there. But after the town's oil boom went bust, Woody saw his father lose everything and pick up stakes and head south to Pampa, a small town in the Texas Panhandle, just like any other foreclosure refugee. Woody followed, and in the spring of 1935, he saw "A dust storm hit, an' it hit like thunder; It dusted us over, an' it covered us under...and all the people did run, singin,' 'So long, it's been good to know yuh.'"

Woody ran, too, but he wasn't a dust-bowl refugee, not technically. He went West to become a cowboy singer. He got a radio show on KFVD radio in LA — his business card read, "WOODY, the dustiest of th' DUSTBOWLERS" — and he met some socialists who taught him to politicize what he'd seen in Okemah and Pampa. He later told the musicologist Alan Lomax that if anybody had told him about the conditions in those camps, he never would have believed it. He became a sort of journalist, reporting from California's "Hoovervilles," makeshift camps of homeless, unemployed migrants. His medium was songs. "Singing lifts the mind above the usual train of thinking," he said.

His songs were the stories of real people he met, full of particular details: "I've been hittin' some hard harvestin', I thought you knowed/North Dakota to Kansas City, way down the road/Cuttin' that wheat, stackin' that hay, and I'm tryin' to make about a dollar a day/And I've been havin' some hard travelin', Lord."

Did the voiceless refugees accept Woody as their voice? Apparently so: The songs were about them, not about him, not directly. There's a pair of archival photos in the traveling exhibit of him performing in a work camp. His back is to the camera; the faces looking up at him acknowledge that yes, he's speaking to, and for, them.

Does he still speak for us now? The income disparity between the rich and poor is greater today than it was during the Great Depression. The unemployment rate is lower, the number of foreclosures is less, but people are more affected by the loss of their investments. There haven't been any dust storms recently, but there are still jolly bankers. ("When your car you're losin', and sadly you're cruisin'... I'll come and foreclose, get your car and your clothes.") And what would he do? Would he blog? Would he Tweet? Would he have his own YouTube channel? Would he go on eternal tour like his disciple Bob Dylan?

Will Kaufman, who spoke at the Tulsa conference, probably has a better guess than most: His book Woody Guthrie, American Radical came out last year. "Woody would be doing exactly what he did," Kaufman said. "He wouldn't have to change a word of his songs."