There has been much debate over the existence of the G-spot. No, not that G-spot. The other one, in the brain, where G stands for God.

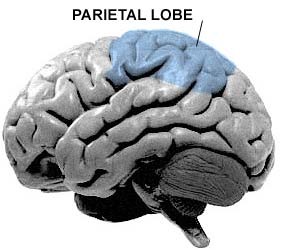

"The spiritual experience is very complex," says Brick Johnstone, a neuropsychologist at the University of Missouri. Johnstone and four of his colleagues just completed a study that shows that the right parietal lobe is connected to feelings of selflessness, which are associated with self-forgetfulness and spiritual transcendence. But that's not the only part of the brain associated with spirituality.

"There's not one spot in the brain that makes you believe in God," Johnstone asserts. Ultimately, he hopes to draw a spiritual map of the brain similar to the ones scientists have now to illustrate all the parts that contribute to the process they call "cognition" and the rest of us call "thinking."

And if spirituality is the result of brain function, then spiritual experiences aren't just limited to believers.

That's good news for us heathens.

Johnstone's current research has been concentrating on the selflessness aspect of spirituality. Other researchers have studied the heightened-experience part, either through increased electrical activity (i.e. seizures) or drugs. (Turns out Timothy Leary's early LSD experiments -- and the recent adventures of Roger Sterling on Mad Men -- weren't so wrong-headed, or self-indulgent, after all. Changes in brain chemicals, namely neurotransmitters, can lead to intense, sometimes life-changing, spiritual experiences.) But Johnstone believes self-forgetfulness can also lead to spiritual transcendence.

In their latest study, Johnstone and his colleagues studied 20 patients who had suffered injuries to the right front parietal lobe of their brain.

The 20 research subjects ranged in age from 18 to 78 and were evenly divided between males and females. Six identified as Protestant, one as Catholic, one as Muslim and ten as "other"; two did not respond at all. All were hospital outpatients, but 19 had reported losing consciousness at some point due to their brain injuries and more than half had experienced some form of amnesia.

The researchers administered a series of surveys to the subjects to measure their feelings of closeness to a transcendental entity (referred to as a "higher power" instead of "God" so as not to offend anyone)and the amount of time they spent in religious activity (ranging from watching religious TV programs to attending services). The researchers also performed a series of neurological tests to measure the subjects' brain activity.

As Johnstone and his colleagues expected, the patients with the most damage to their right parietal lobes were the ones who reported the most spiritual feeling. (Johnstone declined to make any cynical jokes concerning the relationship between religion and brain damage. He is well aware that he lives in Missouri.) Spiritual feeling was understood to mean self-forgetfulness.

"The right side of the brain is more self-oriented," Johnstone explains. "The left side of the brain is other-oriented. People with injuries to the right parietal lobe tend to be more altruistic."

Johnstone's latest research confirmed earlier studies of Franciscan nuns and Buddhist monks which had shown that when the nuns and monks were deepest in prayer or meditation (for the purposes of research, these were considered two different names for the same thing), there was less blood flow to their right parietal lobes. That part of the brain was essentially shutting down.

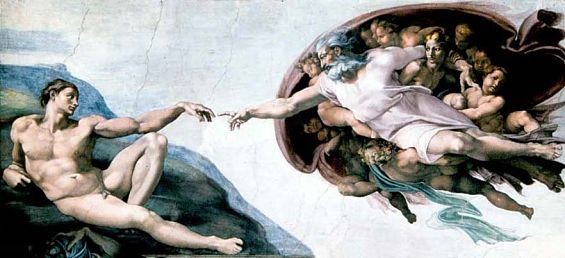

"In those heightened states," says Johnstone, "there's no sense of self, no self-other dichotomy. There's a sense of unity."

That reaction, Johnstone hastens to add, is not necessarily confined to a conventional religious experience.

"A lot of people experience that with music," he says. "Sometimes I go see a band and the guitar player is so far gone, he's lost in the music. Runners also lose themselves. Nature tends to minimize the sense of self. There are a lot of ways to minimize the self. And the blood flow to the right parietal lobe would be less in runners or musicians.

"Culture influences the experience of the selflessness process," Johnstone continues. "It's like language. Everyone is disposed to develop language, but the way it's expressed is based on culture. In Missouri, I speak English. But somebody who grew up in Berlin would speak German. You experience language differently."

In his next phase of mapping spirituality in the brain, Johnstone will be studying people with seizure disorders. Earlier studies have shown that people who experience excessive electrical activity in the temporal lobe show an increase in religious feeling -- and also sexuality. (Johnstone notes that in some cultures, the two are closely linked.) He'll also be trying to determine if there's any neurological basis in the existence of archetypes -- "that Joseph Campbell stuff" -- and what other portions of the brain affect spirituality.

"Look at cognition and personality," he says. "The brain controls both. But there are many aspects of cognition and personality. There are different aspects of spirituality, too."