I barely remember the St. Louis football Cardinals. I was only eight years old when they left; the extent of what I really have of them is an old nylon backpack in burgundy and a glass mug with the gridbird logo on the side. Even so, the team has a special little place in my heart. I suppose it probably has a place for most of us, regardless of our actual feelings for the team and its -- ahem -- owners.

In that weird collective way that cities have of assimilating sporting teams, the Cardinals are a part of the St. Louis experience, a part of the unconscious mind of the city. The ending of the story may have been ugly, but the journey to get there was still something special.

Slide Show

Slide ShowSadly, the landmark downtown location is now closed, leaving us only with the Westport location. I remember once, when I was seven years old, my entire family went down to Dierdorf and Hart's for dinner, to celebrate some sort of special occasion. For the life of me, I cannot today recall what the occasion was, but I do know there were about twelve of us going.

I had never been in a place that fancy before, all mirrors and dark wood, and I was more than a little bit intimidated. The food was wonderful (I think), but what I remember most was that feeling that I was getting a glimpse of the grown-up world, a world full of women in sleek evening gowns and men in tailored suits, a world that seemed bright and shiny and impossibly distant.

Dierdorf was there that night, a mountain of a man with a deep, rumbling sort of voice that frightened me more than I was willing to admit. He came by our table, thanked us all for coming, and asked me specifically, in that way that adults have of talking to the very small, if my steak was okay. I summoned up all my courage and told him it was magnificent. It was the most complimentary word I knew, having just learned it earlier that week from the vocabulary flashcards my grandmother had bought me.

Dierdorf laughed aloud, said what a little gentleman I was, and how glad he was that I enjoyed it. He spoke a bit more to the adults at the table, but I had no idea what was being said. I could only marvel that I had forayed into that rich and sleek society, and had come back with the laughter of a giant in my ears. Life could not have been better.

I know all the statistics from both Hart and Dierdorf, and I've heard all the stories from my father about how great each were, but I honestly don't recall seeing either of them play. To me, when I hear either name, I think only of that night when I was seven, eating in a restaurant fancier than anything I had ever imagined before. If any players could ever claim to be a true part of the city, these two could.

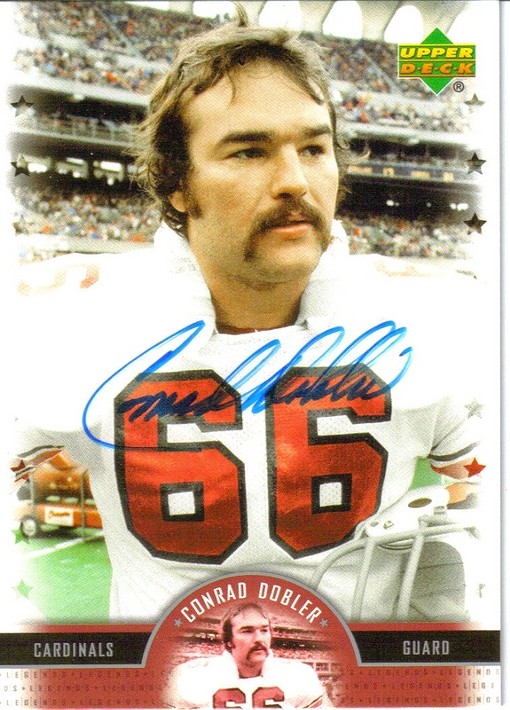

Conrad Dobler

Dobler is today perhaps the greatest poster boy that Mike Ditka and his efforts to get a fair shake for retired NFL players could ever hope for. During his heyday with the Cardinals, Dobler was known as, quite possibly, the dirtiest player in the NFL, and one of the dirtiest ever. He was also one of the best offensive linemen in the league.

Dobler was taken by the Cardinals in the 1972 draft, and immediately stepped in and began contributing. Jim Hart, the quarterback during Dobler's tenure with the Cardinals, has said before in interviews that the only reason he can still walk around with relative ease is because Conrad cannot. Doing the job in the pits year after year, Dobler took tremendous amounts of punishment. He was elected to the NFL Pro Bowl three consecutive years, from 1975-1977, all the while building his reputation as one of the most vicious and tenacious players in all of football. You want to know about Conrad Dobler? This very

Riverfront Times profiled Dobler in a story that says it all.

Like so many of his brethren, Dobler has paid the price for his on-field exploits. He is 90 percent disabled today, a result of the battering he took all those years ago. He has had numerous surgeries, and still needs more, to try and repair some of the damage that had been done. Unfortunately, also like so many others, Dobler hasn't been able to get disability benefits from the NFL Player's Association. His wife Joy was paralyzed after falling out of a hammock in 2001, and the combination of medical bills from the two of them have nearly destroyed the Doblers.

In 2007, Phil Mickelson, the professional golfer, learned of the Dobler family's plight, and offered to pay for their daughter, Holli, to attend college in Miami, Ohio. When Dobler asked Glenn Cohen, Mickelson's lawyer, why he was willing to pay for Holli's education, Cohen answered, "Because he can."

And so I'll leave you with that, the story of Conrad Dobler. I didn't meant to turn this into a tirade against the NFLPA, but hey, it happens. We have a franchise going to the Super Bowl for the first time in its history, a league that continues to rake in the profits, and a sport that couldn't be healthier, and then on the other hand you have Dobler.

The Cardinal franchise was built on the backs of men like him; the NFL as a whole was built on men like Dobler. Yet while the Cardinals are enjoying a new era of prosperity the likes of which they've never known, a man like Conrad Dobler still needs additional surgeries in order to continue walking. His wife is wheelchair bound. And the NFLPA doesn't want to do fuck all for him.