David Menschel, a criminal defense attorney and criminal justice activist from Brooklyn, New York, spent Wednesday visiting municipal courts in north St. Louis County. What he found, he says, was "the new Jim Crow."

Menschel tweeted what he saw: predominantly black defendants, most without defense attorneys, arguing against dominant prosecutors in front of deferential judges on minor charges, such as sleeping in an apartment without an occupancy permit.

The effectiveness of north St. Louis County municipal courts was thrust into the spotlight in August, when a police officer from Ferguson, a north-county municipality, shot and killed unarmed teen Michael Brown. Protesters who took to the streets in Ferguson say Brown's shooting was the ultimate expression of the contemptuous, preying nature of criminal-justice systems there.

See also: ArchCity Defenders: Meet the legal superheroes fighting for St. Louis' downtrodden

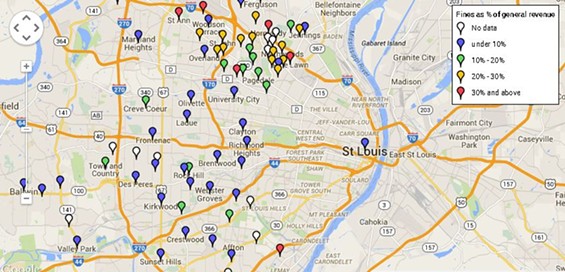

Twenty municipalities in north county derive at least 20 percent of their general budget from fines and fees collected in courts, according to a report from Better Together, which advocates for reunifying the city and county. Those twenty cities are on average 62 percent black with 22 percent of residents living below the poverty line; compare that to St. Louis County overall, which has a 24 percent black population and where 11 percent of people live below the poverty line.

"It becomes all too clear that fines and fees are paid disproportionately by the African American community," the Better Together report reads, especially considering how police are 66 percent more likely to pull over black drivers than white drivers, according to the attorney general. "In other words, these municipalities' method of financial survival -- bringing in revenue via fines and fees -- comes primarily at the expense of black citizens."

That's what Menschel saw Wednesday. He started in Velda City, one of about thirteen small cities clustered within a three-square-mile area in north St. Louis County:

Headed to municipal court, Velda City, St. Louis County, Missouri. pic.twitter.com/mtSSPcLO5z

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014In Velda City muni court, more than 30 people in courtroom apparently waiting to pay fines. More than 90% black.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Judge, clerk and bailiff also black.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Defendant says he previously failed to appear to pay fine because he had to work.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Judge tells indigent defendant he should speak to an attorney. Of course Velda City does not provide public defenders to indigent defendants

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Woman sitting next to me (assuming correctly that I'm an attorney), says "you should file something against the police in Velda City."

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Woman in court for driving wo/license. Judge asks if she drove to court. She says yes. If she hadn't come to court, warrant would issue

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014"The municipal court system financially exploits people of little financial means," Harvey told Riverfront Times. "It works really well for people who have some money. It doesn't work at all for people who don't. And I don't think [the government knows] how serious of an impact it has outside of the financial part. They don't think about the next step, and the next step, and this sort of domino effect."

Defense lawyers would help poor defendants navigate fines and warrants, but Menschel didn't see many on his visit.So far seen ~10 cases. Zero defendants represented by counsel.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014This isn't so much a court; it's a collection agency with the imprimatur of law. #stlouiscountymunicipalcourts

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014As a defense attorney it's weird to see a "court" without defense lawyers. Makes the whole thing seem illegitimate. #stlouiscounty

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Also judge is so deferential, the court is effectively run by the prosecutor. #stlouiscounty

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014"Attorneys I spoke to say the regulation can end up being a way to enforce antiquated local laws against unmarried cohabitation, and judging by comments you sometimes hear in courtrooms or from local officials, a way for police and prosecutors to essentially fine people for having premarital sex," writes The Washington Post's criminal justice blogger Radley Balko, who last month published an in-depth and damning look at local courts, "How municipalities in St. Louis County, Mo., profit from poverty."

Trial for lack of occupancy permit. Cop (only state witness) gives wrong address. Defendant wasn't owners/on lease. Judge finds guilty

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Prosecutor & judge seem to suggest that if one sleeps over w boyfriend & is not named on his home's occupancy permit, one is guilty of crime

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Woman just fined $25 for sleeping over at her boyfriend's house without being on occupancy permit. #stlouiscounty #thenewJimCrow

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Bel Ridge even more offensive than Velda City. Just bilking people for money. Judge and prosecutor openly dismissive of defendants

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014In Bel-Ridge court cashes out at about $100 a minute.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 16, 2014Criminal justice system is like a factory, but instead of building things, it destroys things.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 16, 2014@AntonioFrench I'm in municipal court in StL county. (See tweets) this is what Jim Crow looks like.

— David Menschel (@davidminbklyn) October 15, 2014Follow Lindsay Toler on Twitter at @StLouisLindsay. E-mail the author at [email protected].