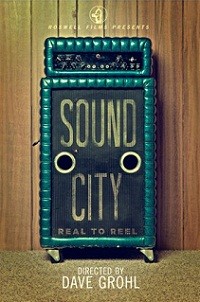

Here's something you don't get to say too often: It's a shame when Paul McCartney turns up. Before McCartney arrives, rasping, puppy-eyed, and eager to have a go at the hot new grunge sound of 1993, Dave Grohl's Sound City is an exciting, sometime illuminating documentary about how a squad of technicians and engineers in a hole-in-the-Valley music studio helped great rock 'n' rollers make great rock 'n' roll. Grohl treats us to just more than an hour celebrating the history of Sound City, the Van Nuys dump where a clutch of rock's great records were bashed out--but the movie's 107 minutes long.

See also: -Dave Grohl On His Film Tribute to the Studio That Gave the World Nevermind

First, in the '70s, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks were lured there by a new $75,000 recording console custom designed by Rupert Neve; later, visiting the studio, Mick Fleetwood heard the resulting Buckingham Nicks LP, and soon the guitarists and singers were all balled up together like mating snakes, recording Fleetwood Mac on that Neve console--and establishing Sound City as the source of one of rock's most glorious drum sounds.

Banging beautifully on a kit, Grohl demonstrates the quality of that Sound City bottom end: that stellar console wired to a drafty room where drums--for whatever reason - boom out loud and alive. The Mac might have made Sound City a name, but much of the music later unleashed there comes from noisier artists: Fear, Dio, Pat Benatar, many '80s hair bands, Nirvana. "It was like Fleetwood Mac all over again," Sound City owner Tom Skeeter exclaims of the boomlet he enjoyed after Nevermind dropped, probably the only time anybody linked those two acts. The highlight, both of the studio's history and the movie, is Tom Petty, whose Heartbreakers rehearsed for the first time and later recorded the urgent Damn the Torpedoes at Sound City.

Damn the Torpedoes exemplifies the crisp, live-band rock sound that room and console excelled at capturing. We see Petty and the band in grubby old video, talking each other through take after take. ("Refugee" alone, we're told, took 150.) We also see Petty today, top-hatted and Muppet-bearded, warmly and weirdly talking up the place and the sessions Rick Rubin held there with the Heartbreakers backing Johnny Cash, years after other studios had gone digital.

Where we don't see Petty is in those jam sessions that take up the film's final half hour. Stevie Nicks, Trent Reznor, Jim Keltner, and Rick Springfield all turn up to play new songs into that vaunted Neve console, now in the possession of Grohl, who purchased it from the now-defunct Sound City. Save McCartney's song, the new stuff isn't necessarily bad--Lee Vigner's is strong, and Reznor's, a collaboration with Josh Homme from Queens of the Stone Age, is inspired. But it all follows too much chestbeating about how "real musicians" and "real men" eschew today's digital recording techniques. Grohl and the band laugh with McCartney about how musicians shouldn't overthink the craft and performance of rock 'n' roll--why, then, did Petty do 150 takes? Why does the best surviving Beatle jamming with the survivors of Nirvana not sound as good as Oasis? Great drums, though.

Follow RFT Music on Twitter or Facebook. But go with Twitter. Facebook blows.