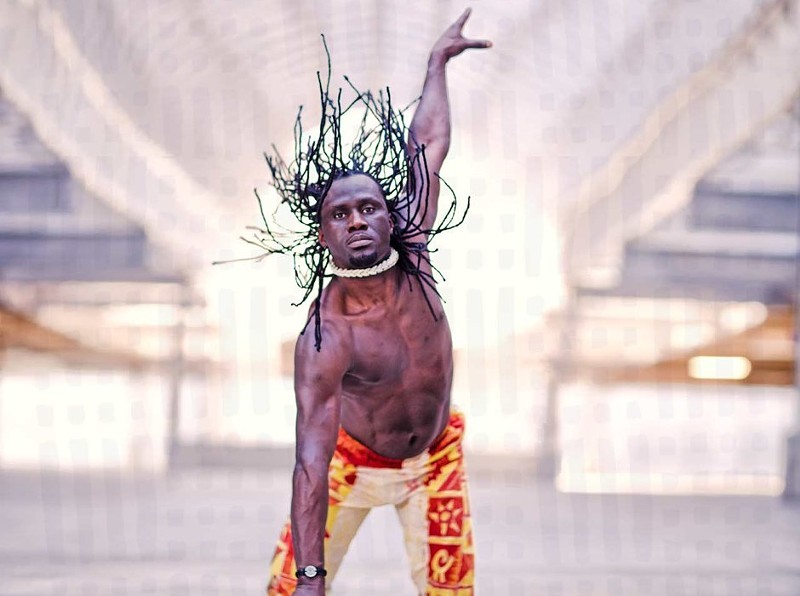

Diadie Bathily has a way of getting people to dance. It works with children, teenagers and adults. It works with the St. Louis Rams, senior citizens and even a stubborn, misinformed little boy named Jason.

Bathily moved to St. Louis in 1998, but he started his career far from the American Midwest.

“I was born in Cote d'Ivoire and my parents are from Mali,” Bathily says. “I grew up in both cultures at the same time. When I was 25, I went to Europe for the first time to teach dance. I moved to the U.S. in July of ’98.”

St. Louis holds a wealth of culture and art. But it’s not the obvious destination for a fledgling dance teacher from West Africa.

“I didn’t pick St. Louis,” he says. “St. Louis picked me. When I was in Ivory Coast, I met an anthropologist named Joseph Hellweg. He was in Africa to research dance and theater. I was teaching dance at the time, and someone told him about me. He visited during one of my classes and just sat down and watched. He was impressed with the way I taught and right away made a phone call to UMSL. I’ve been in St. Louis ever since.”

Bathily is too kind to admit it at first, but he says Americans are a little slow when it comes to learning West African dance.

“Teaching here is really different from teaching in Cote d’Ivoire,” Bathily says. “The key is to break the dance into pieces. You have to explain everything, from the technique to the cultural context. When I taught in Africa, the children would get it right away. Dance is already part of the culture.”

Teaching in a foreign country carries a whole set of unique challenges. But there’s one instance in particular that Bathily remembers more vividly than any other. It all started with the wild imagination of a schoolboy.

“I will never forget it,” Bathily says. “I will never forget him. The experience will mark me forever. I was teaching a P.E. class to second graders at an elementary school in St. Louis and there was this boy named Jason. Before class, the P.E. teacher told me, ‘Diadie, leave this boy alone. He won’t do anything in P.E.’ So I let him be at first. But the second day, I said, ‘You know what? I’m going to keep trying.’ So I told the boy, ‘You’re going to try today.’ He says, ‘No. I’m 100 percent not going to dance.’ So I said, ‘Give me one reason, just one. If you give me one reason why you don’t want to do West African dance, I’ll leave you alone.’ He said, ‘If I do West African dance, I’m going to turn black.’

“I was shocked,” Bathily continues. “I didn’t know how he came up with the idea. So I told him, ‘Yes, you might turn black. But a lot of my white friends who turn black, they try it out first. And only some of them turn black.’ I told him it starts with your toes. So if you try today, and your little toe is black tomorrow morning, it means you’re going to turn black. But if you don’t change, that means you will stay white. So the boy got up, danced a little bit, and then went to sit down.

“The next day, he got up in the morning and ran to his mom. ‘Mom! Mom! Look at my toes!’ His mom had no idea what was going on. Every morning he’d get up. ‘Mom! Mom! My toes are still white!’

“Soon, he started to really get into the class. He was amazing. The mom came to school to figure out what was going on. Ever since P.E. changed, he’d been talking about his toes. So I explained what happened, and she started laughing tears. She told me she doesn’t know where he got this idea. I told her it didn’t offend me. Lots of people look for some kind of excuse or protection for something. Usually, it doesn’t make any sense. I was just happy to help him. Ever since then, he’s been more warm and open to everything. I was sad when it was my last day. I will never forget that boy. I don’t know where he is now, but I would be so happy to see him.”

Bathily’s list of students ranges from the St. Louis Rams to the elderly. And there’s a unique story from every class. The Rams grunted every time they moved: “Hoo, hah, hoo.” The elderly blocked him from entering the building because he had canceled the previous class. They were upset. Many hugs later, they lowered their canes and let him back in the building. West African “wheelchair dancing” commenced soon after.

After teaching for five years, Bathily started a professional dance company called Afriky Lolo that tours across the country, especially at Universities. Recently, Bathily created a fitness company called Timbuk. Needless to say, he keeps busy.

“My question is always: ‘what can I do with African dance?’ It’s a great source of cultural education, but I feel like it can be more than that.” Bathily says. “In fact, I know it can be more than that.”

Learn more about Diadie Bathily and Akriky Lolo via the official website.