Methodist pastor Minji Stark makes breakfast and prays each morning with five Korean women who live at a home near Lambert St. Louis International Airport.

She works mainly with other women to provide assistance because "women together making peace. Men together making war," she says, laughing.

She would know.

Stark, who is from Seoul, South Korea, met her husband in 1977 while he was serving in the U.S. Air Force, stationed in her country. She was working on the base, and they started talking while he was waiting to get picked up.

"He was a good Christian man. We would go together to church," Stark, now 69, says.

They married in Korea, then moved to Augusta, Georgia, in 1979. From there, they went to military bases in San Jose, California, and then Misawa, Japan. That's where Stark started attending a Baptist church and Bible study classes and became a born-again Christian.

In 1986, the couple moved to Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. A year later, when her husband left the military, they moved to St. Louis. She and her husband had two children and now enjoy five grandchildren.

But Stark admits that she was nervous about getting involved with an American man. Many marriages between Korean women and U.S. soldiers ended badly.

According to some estimates, 100,000 marriages between Korean women and American soldiers have taken place since the U.S. started occupying Korea in 1945. The divorce rate? Possibly as high as 80 percent, according to Katharine Moon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Center for East Asian Studies and the author of Sex Among Allies: Military Prostitution in U.S.-Korea Relations.

The marriages ended for a variety of reasons: "language and cultural barriers, American racism, unfamiliarity with Korean customs and abuse," Moon says. Often, the women were then left to navigate life in the United States on their own with limited English proficiency.

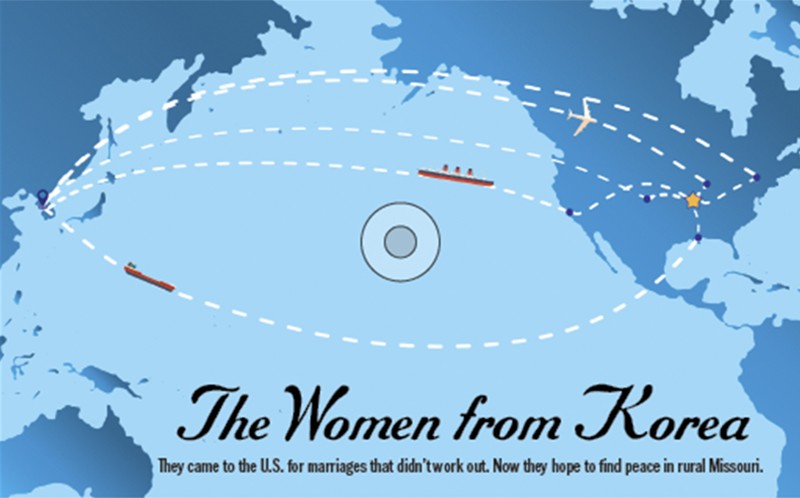

And so for the last few decades, Stark has driven across the country to pick up Korean-born women from hospitals and homeless shelters in Colorado, Louisiana and New York, and then drive them back to St. Louis, where her organization provides them with food and a place to stay.

Her ultimate goal for some time now has been to move the women out to a 112-acre property in Robertsville, Missouri, just past Pacific on Highway 44. There, she envisions a bucolic life: The women can grow and sell organic vegetables and "get closer to nature," she says.

She wants to help the women find a purpose so they can "serve somebody, not just having someone serve them," and to build "hope in Christ."

She calls it Peace Village.

Stark's organization, the National Association of Intercultural Family Mission, has helped Korean women throughout the United States with housing, jobs, food, translation and even funeral services. In the St. Louis area, Stark has provided housing for more than a dozen women.

The organization achieved non-profit status in 1999 and maintains a skeleton framework. Records show no paid staffers and no highly paid consultants. The money that comes in — $213,051 in 2014, the most recent year its tax returns are available — goes almost entirely to help house and support Korean-born women who find themselves in the U.S. and in need.

The women who Stark has helped could not or were not able to share their stories, either because of a language barrier or because of past trauma, Stark says.

A majority of the marriages between U.S. soldiers and Korean women from 1950 to 1980 started in the bars and brothels that surrounded the military bases, according to Moon and other scholars.

The United States military and the South Korean government collaborated to regulate prostitution to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. South Korean officials also encouraged the practice in order to keep soldiers happy because they feared the American military would otherwise leave, abandoning the democratic country to its communist neighbor to the north.

Meanwhile, the women who went to work in camp towns saw marrying soldiers as a way to "live the American dream," says Moon.

But in Korea, there was a "very puritanical, moralistic and very judgmental society," Moon says. The women who had been sex workers and then married outside of their Korean ethnic group were seen as "double-pariahs."

Many of the women were abused by pimps or bar owners in Korea and then continued to face physical and emotional abuse in their marriages. In one case, an American man did not allow his wife "to eat kimchi in the house. She was not allowed to eat her most important native food," Moon says.

"I think there is this mindset among the American G.I.s who went to brothels and clubs that these women were disposable, and some of that mentality may have carried over into the more serious relationships," says Grace Cho, the author of Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and The Forgotten War, which includes her own family history.

If the marriages broke apart, the women had trouble finding help in the Korean community because of the assumption that they had been prostitutes, or at the very least a "traitor for sleeping with Americans," says Cho.

As such, women in the Korean War generation are often ashamed of their past.

Cho, who has a Korean mother and an American father, knows little about how her parents met. Her father was in the Merchant Marines; her mother worked at a naval base in Korea. They only discussed their relationship "in the vaguest terms. There was never any concrete narrative."

"It's not talked about in America, and it's not talked about in Korea because it's considered something shameful," she says.

Once ostracized by both Americans and Koreans, some of the women ended up homeless, which added another layer of shame and secrecy.

"Koreans still don't have a concept of homelessness; it's just, you're a beggar," says Moon.

Moon, who is Korean, has never been to Peace Village, but she says that within the Korean Christian community, such a ministry is unique.

"Even though you are seeing a church that tends to them, most of them have been shunned by Korean Americans in the United States," she says.