And while it's one thing for those theories to swirl around Facebook, or even to appear in popular niche national outlets like The Root, last month the Associated Press got in on the story.

Its March 17 story, "A puzzling number of men tied to Ferguson protests have died," was immediately republished and repackaged in local papers across the country, as AP stories tend to be. Many outlets ran versions of the story under its given headline, but others saw fit to subtly alter the story's operative adjective: The deaths that were first "puzzling" became "suspicious," "mysterious," "strange" and "sinister."

The AP itself issued a clarification on the story on March 21 — amending its own headline to "Activists unnerved by deaths of men tied to Ferguson protests." But the story had already dumped gallons of fuel on a fire of speculation. It demonstrated just how compelling the conspiracy theory remains, no matter how many times its particulars fail to show evidence of a pattern.

"Two young men were found dead inside torched cars," the AP's Jim Salter began the story. "Three others died of apparent suicides. Another collapsed on a bus, his death ruled an overdose."

Those six deaths serve as the foundation of story whose central point was countered within the story itself — police told the AP that the deaths are not related to the Ferguson protests; no specific evidence was presented that suggested otherwise. And yet, Salter writes, the deaths generated "attention on social media and speculation in the activist community that something sinister was at play."

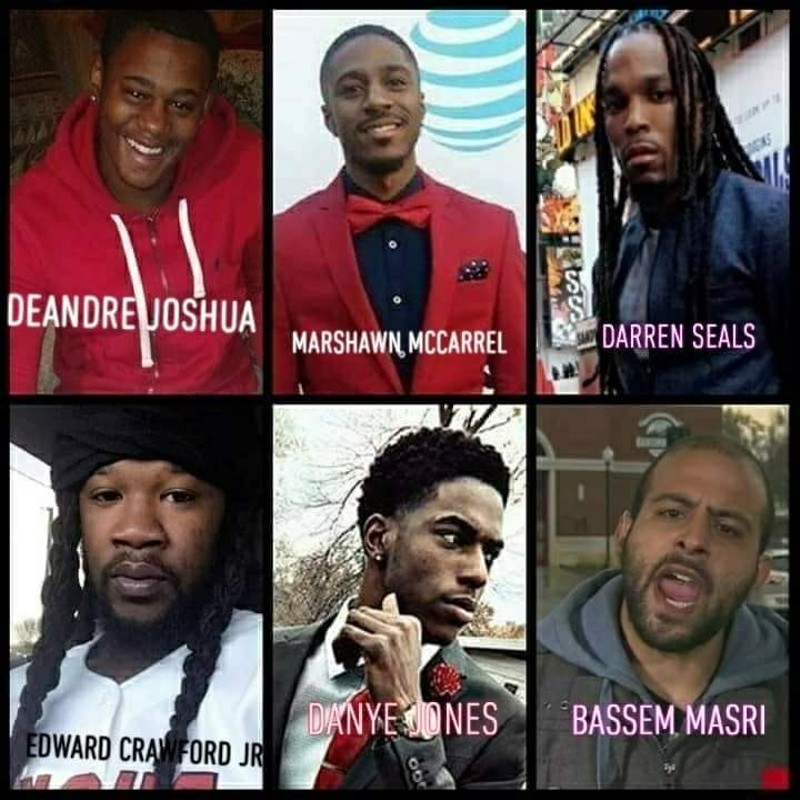

That speculation only grew on social media last week. Images like the one below, showing the six young black men named in the AP story, were shared thousands of times.

The AP story includes quotes former U.S. Senate candidate Cori Bush, a protest organizer who suspects white supremacists or police sympathizers of orchestrating various acts of harassment, including running her car off the road, vandalizing her home and shooting a bullet into her car.

"Something is going on," Bush says in the AP story. "I’ve been vocal about the things that I’ve experienced and still experience — the harassment, the intimidation, the death threats, the death attempts."

The second source in the AP story is the Reverend Daryl Gray, who rose to greater prominence during the 2017 protests over the acquittal of ex-St. Louis Police officer Jason Stockley. Gray is described finding a box in his car containing a "six-foot python."

So what is really going on? On Friday, that question was given its most deeply reported evaluation to date, courtesy of the radio program This American Life. It sent New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb to investigate the story, but rather than go deeper down the AP's path of suggestion, Cobb's reporting focused on activists caught up in the conspiracy mindset.

The segment, "Show-Me State of Mind," raised familiar critiques to the theory that the deaths of the six young black men are related. For instance, Deandre Joshua, 20, was in fact found shot in a burned car on the night of a grand jury's decision not to indict the Ferguson officer who had killed Michael Brown — but, according to Joshua's parents, their son had never attended a protest. He wasn't, as rumors have claimed, a grand jury witness, much less one who had been murdered to ensure his silence.

Other cases mentioned in the AP story present equally murky reasons for being "related" to Ferguson. MarShawn McCarrel, 23, is described by the AP as having been "active in Ferguson," but his death came by suicide in 2016, and was committed on the steps of the Ohio statehouse.

In This American Life, Cobb delves into Joshua's death, but he notes that the more recent deaths, involving protesters with much clearer connections to Ferguson, have made the theory much harder to ignore.

There was Edward Crawford, 27, arguably the most visible Ferguson protester — he was the subject of an instantly iconic photograph showing him throwing a tear-gas canister back at police — who died of a self-inflicted gunshot in May 2017.

At the time, Crawford's father maintained his son's death was an accident, not suicide. But that didn't stop news of Crawford's demise from reviving that familiar question — what is really going on?

"It is now not coincidental," tweeted then-Missouri Senator Maria Chappelle-Nadal after Crawford's death. "There is a murderer targeting activists from #Ferguson. #WeAreNotInvisible #Resist."

Thank you. It is now not coincidental. There is a murderer targeting activists from #Ferguson. #WeAreNotInvisible #Resist https://t.co/cZV8VniCrO

— MariaChappelleNadal (@MariaChappelleN) May 5, 2017

However, it was the 2018 death of Danye Jones that gave the conspiracy theory its biggest push into the spotlight. Jones, the son of prominent protest organizer Melissa McKinnies, was discovered dead in October, hanging from a tree in his mother's backyard in Spanish Lake. In this case, the suggestion that Jones' death was something other than a suicide (as police investigators have insisted) came not from social media, but McKinnies herself, who wrote on Facebook, "They lynched my baby."

Even so, for This American Life, Cobb peels back layer upon layer of the theory. The picture that emerges isn't "NASA faked the moon landing," but, he says, "clusters of suspicion, brushfires of doubt about the official narratives of what was happening around them."

That doubt is present for activist Ashley Yates, who concedes in an interview with Cobb, "Can I say that right now, in this moment, there is a conspiracy against activists? No, because again, I don't have the hard, concrete evidence."

Still, she adds, "Can I say that it is likely? When I take into account my experiences, the experiences of people around me and those before, absolutely."

There is no dispute that the day-to-day experiences of activists like Yates frequently involve death threats made over social media. In the episode, protest organizer Ohune Ashe tells Cobb that she continues to receive threats on her life. She won't dismiss the deaths of other activists as mere "theory."

"When you have a list of names of people who are known," Ashe says on the episode, "and they are dying in this mysterious way, as an activist or as a person that people deem active, you wonder, are you next?"

There is another variable in the mixture of grief and paranoia — St. Louis kills young black men at an astonishing rate. Life expectancy in predominately white and affluent west St. Louis county are in the 80s. Life expectancy in some parts of mostly black north county is in the 60s. The rate of homicide victimization for Missouri's black residents, meanwhile, is ten times higher than the national average for people of all races. It's 2.5 times higher than black people in other states.

DANNY WICENTOWSKI

Bassem Masri, left, was a notable livestreamer during the Ferguson protests of 2014.

Sidestepping the role of violence and poverty can make it seem like a cluster of deaths might truly involve a killer stalking their way through a list of activists. But that perspective misses part of what it actually means to live in the places that produced those activists.

When Ferguson livestreamer Bassem Masri died on a St. Louis bus last year at 31, his name was added to the grim ledger of supposedly murdered activists. According to a medical examiner's report, though, Masri died of a fentanyl overdose.

"When he passed away, people said, 'Well, what happened?' Well, what happened was, he was still in the ghetto," rapper Tef Poe, Masri's former roommate, tells Cobb.

"This is the reality of the circumstances," Poe says. "And I'm pissed off about the fact that I keep having to bury people. And people are acting like Santa Claus is coming down here killing folks."

In the interview with Cobb, Poe calls the theory of an unknown killer targeting activists "unicorn stuff." While he doesn't directly criticize others for partaking in the theory, Poe suggests that if he were to get shot, no matter the circumstances, he would join Crawford, Jones and the others as a topic of conspiracy. It would be his photo on a viral Facebook post.

And in a city like St. Louis, where people are shot and killed every day, it's only reasonable to presume that this won't be the last time the death of a young black person — even one not related to the Ferguson protests — raises the same puzzlement.

Later in the interview with Cobb, Poe remarks that a serial killer targeting local protesters would be far less effective than the forces already working against young people in St. Louis.

"They don't have to send a firing squad into the apartment to kill you," Poe explains. "Now, all they gotta do is leave you in north St. Louis to die."

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]